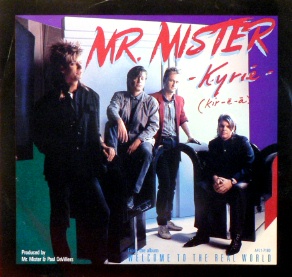

A quintessential representation of its time is Mr. Mister’s synthesizer- propelled “Kyrie” which hit Number One on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart in March of 1986, and remained there for two weeks. With lyrics written by band outsider John Lang and music by members Richard Page and Steve George, the track also charted at Number One on the Mainstream Rock Songs chart, and was a Number 3 Adult Contemporary song as well.

However, Page recalls that he wasn’t initially very keen on the idea of the name of the song. “I figured we’d be pigeonholed as a Christian band and I didn’t think that’s what we needed at the time, but John kept saying, ‘It works so well with the melody,’” Page says. “We got into the studio and I was still sort of against it, [but] by the time we finished most of the track, there was no turning back.”

Page says that the synthesizer revolution was in full swing at the time when they made “Kyrie” and the bandmembers were like kids at Christmas with their new toys. “There were a lot of new technologies happening, a lot of new synths, like polyphonic synths just started to come out. It was like, ‘This is so much fun, you can program this and it will play it back and you can play something over it.’ It was mind-boggling. We never really thought how we were going to reproduce it live,” Page says with a laugh.

The band, which included Page, Steve George, Steve Ferris and Pat Mastelotto, cut “Kyrie” at Ocean Way Recording (Hollywood), moving between Studios A and B, and co-producing with producer/engineer Paul De Villiers. They found De Villiers through their friend singer-songwriter Marc Jordan; the bandmembers visited De Villiers in Irvine, where he was mixing concert sound for Yes, and they asked him to co-produce and record them. That was the beginning of their creative relationship.

De Villiers remembers that when he first heard “Kyrie,” he thought it was complete, but he felt it could be even stronger. He set about fleshing it out on the API board in Ocean Way Studio A, and he says studio owner Allen Sides often came around to help out.

The band first attempted to track “Kyrie” entirely live, but the team felt the performance was unsuccessful, so they decided to create the song part by part, yet endeavor to make it sound live; this is the objective that De Villiers kept throughout the entire process.

“When you could sync everything up, there was a power to perfect time that none of us had ever experienced,” De Villiers says. “Pat worked everything up on his beat box and then he said, ‘Here are the parts.’ We overdubbed all the drums independently and built up the tracks very slowly. We overdubbed the cymbals separately.”

The first element they had going on was the sequenced bass line they recorded with a click. “That was on a Prophet-5 I think, which was the big synth at the time. I had just gotten one and I was so taken by it.” Page says. “We laid that down and we came up with the long intro which was Steve’s thing, and I did that roboto “Kyrie” over the top. [Then] the drums—some of it was triggered, some of it was played—and guitars.

“Paul loved his AMS digital delays and reverbs,” Page continues. “He had some other gadgets that kind of defined the sound and what we were doing and he used them wisely. He had some ideas about how things might be voiced.”

De Villiers says his affinity for AMS came from Peter Gabriel, and Sides had beautiful compressors; he probably used some LA-2As and old Teletronix equipment. “Not much reverb, because we used the rooms so much,” De Villiers says.

Page says the vocals took the longest because it was just him and George singing, and De Villiers was multitracking them in a most unique and methodical fashion. De Villiers recorded them singing together through an AKG C12 several times sans effects. A process was devised to simulate a choir, inspired by bands like Queen and Yes.

De Villiers placed X’s on the ground to mark where people would be in a 30-piece choir and the duo would sing from different locations, moving from X to X.

“There would maybe be five in the front and six behind [in an actual choir]; it narrows down and a lot of weight is in the middle. I [used] one microphone, and every take was done with that in mind,” De Villiers recalls. “I didn’t have to pan things. It took a lot of tracks and a lot of bouncing. Steve and Rich would do a track and I would say, ‘Great, move to the next X.’ ‘Great, next one.’ ‘Great, next X.’ The last one was about 20 feet away from the mic. The mic stayed in the same [place], so it was as if each individual person in the choir came out and stood in their place and sang, and then we put it all together.”

The single ends on an a cappella vocal and the album ends with a fade-out. Page explains that this was a radio-related decision.

“We had just been through this with ‘Broken Wings,’ which was well over five minutes. Everyone said no [radio stations] would play it if they saw that [it was longer than] five minutes. We tried to edit it, but we couldn’t figure out an edit. Finally one of us just said, ‘Just write four-thirty-something on the box and nobody will ever know,’ and nobody ever did,” Page says. “When the same thing came up in ‘Kyrie,’ we thought, why don’t we just drop everything out and have an acapella ending, and it was very dramatic.”

Page says De Villiers got a really cool sound with Mastelotto’s drums… “for the time.”

Mastelotto recalls that, for him, work on the song began on a day off at the Miyako Hotel in San Francisco when he took his Linn Drum machine and a cassette of the song that Page and George had given him up to his room. His bandmates had asked if he could find something better than the samba-ish groove they had come up with.

“When I heard the melody, I instantly heard it as a Zeppelin/John Bonham, a little bit slower, thing,” Mastelotto says. “I got the tempo and chunky feel it’s in and made a little drum beat for them. The little a cappella breaks and the way the ending happens were my ideas because I had worked so much with Mike Chapman and Peter Coleman, and they had done things like ‘Heartbreaker’ and ‘Hot Child in the City,’ so I knew how much radio loved those little vocal breaks, so I suggested that.”

When the band went into the studio with De Villiers, they felt like they couldn’t get a good headphone mix, so Mastelotto suggested he lay down the drum machine and the band play guide tracks so he could put the drums on later. The Linn ended up sticking, though:

One night in the back room that Mastelotto described as “the big linoleum room,” Paul and he began to experiment. “In those days I used a Simmons SDS5, the old analog Simmons brain, and plugged my Linn drum into that,” Mastelotto recalls. “When we printed those Linn drum things, it sounded really good. We put those big UREIs in the room and I took an old Camco snare I had that had a big fat snare strainer on it and set it sideways right in front of that speaker, and Paul miked the snares underneath that. We pumped the snare drum out to those speakers until it made the snares buzz and we recorded that. We verified the takes—slowed it down a little bit and then up a little bit—so there were three passes we printed of that snare drum being activated by my Linn drum through those UREI speakers. That’s why about halfway through the song the snare drum gets a lot bigger. It sounds like it’s doubled with tom toms.”

The kick drum was sounding small, so they put it through the UREIs also. While De Villiers and Mastelotto were in the control room, two second engineers put Neumann M50 mics on big booms with wheels and pushed them away from the speakers.

“We hit a spot about 15 or 20 feet away from the speakers where both Paul and I went, ‘Whoa! Stop. Bring the microphones back about one foot,’ And we printed that,” says Mastelotto.

On the drums, De Villiers recalls using AKG C12 overhead mics, Telefunken 251s on the toms, Neumann M50s for room mics and probably a Beyer M88 on the kick. When they ended up mixing that track with Mick Guzauski, Mastelotto says he told Guzauski he wanted to turn the room up; he loved the way the room mics sounded, but they were out of sync.

“[Mick] said, ‘I can fix that for you. We just flip the tape over backwards and we put a delay on the sound you’re talking about—the room mics—and we print it to an adjacent track. Then we flip the tape back over and now it’s ahead so you use a delay to bring it back in sync,’” Mastelotto recalls. “Guzauski taught me that trick.”

Page remembers the first time he walked into Conway Studios to meet Guzauski; there were feet sticking out from under the console. “He was napping under there,” Page says. “We woke him up and he was groggy. He had this scraggly beard and he looked like a homeless guy. He said, ‘Sorry I had to take a nap. Let me hear what you got.’ We put on ‘Kyrie,’ and literally four bars in he said, ‘I’m doing this.’ It hadn’t been a sure thing that he wanted to do it, but I think he started that day.”

Page says the song was a product of the times. Today it would be recorded totally differently: “Maybe with acoustic guitar and tablas,” he says with a laugh. But he’ll leave well enough alone.

De Villiers comments that indeed the instrumentation, recording and mix is “very ’80s.”

The vocals have transcended time, though. If you’ve heard Page perform the song in Ringo Starr’s All-Star Band, Page’s vocals match the record spot on… they’re beautiful to behold.