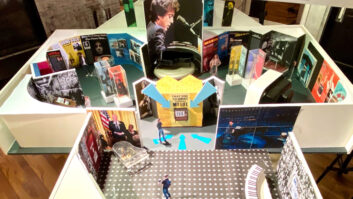

Photo: Ed Freeman

Dave Lichtenstein is an avid surfer, so it’s not really in his nature to feel the pressure to do anything too quickly. But he’s also an artist, so he knows what he wants and he cares about quality sound. After nearly 30 years in and around the recording industry—as an engineer, writer and performer, with various sidetracks along the way—Lichtenstein knew he wanted to build a big room that was comfortable for musicians, a place where a band or a small orchestra could come together to play. Now he’s got one, and it’s a beauty.

Located in the hip and burgeoning Uptown district of Oakland, Calif., 25th Street Recording is a modern take on a classic analog tracking room: 20-foot ceilings, large booths, a very “live” sound and a spacious control room that is equally suited to tracking or mixing, stereo or surround. It’s the type of studio that just isn’t being built as much today as the industry moves toward a more direct-line, production-oriented, in-the-box model. But Lichtenstein has always followed his own path, and after completing a record in 2007, he looked around the San Francisco Bay Area and thought there was a hole in the local studio scene that he could fill.

“In the summer of 2007, I went in to Fantasy Studios to record 13 songs I had been working on at home and in my space at Soundwave [rehearsal facility],” the soft-spoken Lichtenstein recalls. “Part of the reason for going in to Fantasy was simply to shake out what it was like to be in a real studio again; it had been awhile since my New York days. We spent about three months, and it was a lot of fun. But right when we finished, Fantasy was going through its changes and we still needed to mix. The only real comparable room to mix in, according to Jeffrey Wood, my producer, was Prairie Sun in Cotati, about an hour north of San Francisco. Like Fantasy, it’s a nice studio, but it made me think that there was room for another big studio in the Bay Area.”

NEW YORK CITY ROOTS

While Lichtenstein is the new kid on the block, he is hardly a Johnny-come-lately to the recording scene. He’s a self-described electronics nerd who started drumming in the fifth grade in Princeton, N.J., formed a band in the seventh grade, learned guitar, took a break to surf for a year, then took a road trip to Dallas with his new band and saw the inside of his first professional studio. He then came back to New York and enrolled at the Institute of Audio Research. “I was always into the ‘sound’ of things back then,” Lichtenstein says. “And I think that’s part of why I wanted to build a studio today. I see signs out there that people are starting to turn back to high-quality sound.”

Shortly before finishing at IAR, he took an apprentice job with Paul Wickliffe at a small 8-track studio on 28th Street in Manhattan. While assisting and sometimes mixing, he also did maintenance, and when Wickliffe started building Skyline Studios in the late-’70s, Lichtenstein got a real-world education in what it took to put a top-notch facility together.

While at Skyline, the first record he did on his own was for Alan Vega of the proto-punk band Suicide, followed by The Fleshtones. Soon after, he was engineering a John Cale session when Cale asked him to sit in on drums. That led to three years of touring with Cale in the early ’80s, throughout Europe and the States. That was followed by the formation of his own band, Cowboy Mouth, where he wrote, played guitar and sang. Then he left that behind and enrolled full time at Columbia University, earning an EE degree in the early ’90s.

Lichtenstein came to the Bay Area in 1994 and took a job writing code for a software company. By 2002, he was back writing music and bought his first DAW—Cubase—then got the rehearsal space at Soundwave, then did the record at Fantasy, then decided he wanted to be a studio owner. But first he needed a building.

Dave Lichtenstein at the API Vision

Photo: Sherri Tantleff

BACK IN OAKTOWN

“Actually, the first few months I spent convincing my wife,” he says with a laugh. “Then I went looking for a building, and that took about two years. I wanted a stand-alone structure, at least 4,000 square feet, with high ceilings and a nice concrete slab. Of course, once we got into the design with Fran, we ended up ripping that out and putting in floating floors, but it was a nice selling point for me.”

Fran is Fran Manzella, the noted studio designer from New York who had known Lichtenstein back when they were both working at Skyline in the early ’80s. The years went by, and then, as Manzella recalls, he “got this call out of the blue from an old friend who wanted to build a studio.

“Dave was in the process of buying the building when we first met, late 2009,” Manzella continues. “I came out for a site visit, and we literally drove into what would become the studio. It was a great host building, a British auto repair shop on the edge of a real up-and-coming area. Dave started to describe for me his vision, which I would describe as rough-and-ready, with a slightly unfinished look but absolutely professional in its infrastructure. Rough-sawn wood, custom-milled, local reclaimed woods. Nothing too detailed, nothing too perfect. The term he used back then was ‘a gallery aesthetic.’ And he was decidedly analog.”

Originally, Manzella submitted designs for both a one-room and a two-room facility. Lichtenstein acknowledges that from a business standpoint, two rooms may make more sense, but he wanted something that separated him from the competition, something that would make him unique, so he stuck with his original vision of a big, live tracking room.

From the initial site visit to the API console install in July 2011 was about 18 months, and while there were a fair amount of changes in the finishing, Lichtenstein stayed true to the original architectural and acoustic design, and he ended up taking Manzella’s advice—albeit a bit more costly—to float four slabs on springs and rip out two steel trusses in the ceiling.

“Dave really liked the look of the open trusses in the ceiling,” Manzella recalls, “but isolation was paramount, and once we decided to float the floors, we had to take them out. Then we decided to replace the roof, and I have to say, the ceiling is fantastic. It’s this old barn-style structure with four segments, so we put in some lighter-steel, bent I-beam construction and were able to maintain the height. Dave liked the height and wanted to keep it throughout. Twenty-one feet in the live room, Fourteen feet in the control room. As designers, we love that.”

While Lichtenstein definitely had a vision for the look and feel, he is not shy about seeking advice from other professionals. When he needed a contractor, all talk led to Dennis Stearns, one of the best in the country. “Dennis was just fantastic,” Manzella says. “A real professional who has been doing this a long time, with great insights and a huge breadth of resources. He has a top crew and a fantastic electrician [Tommy Thompson]. Do you know how hard it is to find a good electrician? They are rare. Dennis is also great with custom woodwork, so all those diffusion boxes and panels along the wall, with that rough-sawn look, he built them all according to the geometries of the spaces.”

Stearns also found the flooring for the studio at a lumberyard in Novato, Calif. It turned out to be reclaimed bleacher seats from a stadium at Southern Illinois University, refinished for floors. The ceiling and front wall of the live room is the rough Douglas fir, burned with an acetylene torch, then coated with five layers of a Brazilian oil. It looks stunning.

The San Francisco Bay Area’s A-list studio construction crew, under the direction of Dennis Stearns, from left: Vince Shaw, Miles Hart, DJ Burns, Stearns, John Ferlauto, Tommy Thompson (Thompson Electric), Kyle Beigel and Freddy Lopez. Not pictured: Aaron Johnson. Inset: studio designer Fran Manzella.

OPENING UP THE CONTROL ROOM

At the time construction started, Lichtenstein still hadn’t selected a monitoring system or a console. He was pretty set on the ATC 400s, and was finally sold following a listening test at EastWest Studios in L.A. He went for full-range surround monitoring, with a dual-sub.

As for the console, Lichtenstein says that while he was definitely going analog, API wasn’t even in the running until he visited Dan Zimbelman at the San Francisco AES in October 2010. Zimbelman invited him out to Nashville, where they spent some time on a Vision at MTSU, then headed over to Blackbird Studio D for a look at the 96-channel Legacy. The next day he booked the order for a 64-channel Vision.

“I checked out every major brand of console, new and reconditioned,” Lichtenstein says. “The light bulb sort of went off for me at the AES show. API is known for its sound, tracking through the mic pre’s—very punchy. Then it’s full surround for mixing, with all-discrete analog circuitry. No ICs in the circuit path. Plus, there are people who love their SSL or they love their Neve, but this was the only console where nobody has a negative opinion. Nobody.”

When it came time to begin amassing equipment, Lichtenstein turned to Stephen Jarvis, one of the best resources and consultants around, and he’s become something of a sounding board, business partner and mic supplier at 25th Street. Much of the gear came from a liquidation at Rumbo Recorders in Los Angeles, where he started picking up some of the classic vintage outboard gear that now dominates his racks. On the day of this interview, they were running the remote to an EMT 240 plate reverb. The Hammond B3 in the photo is Daryl Dragon’s—the Captain’s—very own from Rumbo.

The outboard racks are a Lichtenstein and Stearns special, something this writer has not seen before in countless studio visits over the years. They are angled and on wheels so they can be rolled out of the way, as they are on the cover, or pulled in lengthwise for the more traditional approach. “I never really understood the producer’s desk,” Lichtenstein says, “because it’s not ergonomic for the engineer to crouch down to make adjustments and turn away from the speakers. And it separates the room into two exclusive areas. This way, we can open it up for a more relaxed listening environment. Or we can seal it off if the engineer prefers.”

The API was installed in early July, and the last few months have involved testing and tweaking. Manzella came out the first week of September to listen and they ended up putting “maybe 1 dB of EQ in the monitors, which can be popped out if it seems to make a difference,” Lichtenstein says. “But we were 95 percent of the way there right when we turned everything on.”

Scott Bergstrom, a recent graduate of Peabody Conservatory’s master’s program in recording, has been hired as assistant engineer and has been central to shaking down the room with cue system testing, patchbay labeling and rack wiring. John Smart, who graduated from Ex’Pression in September, has also been brought onboard. They all love the sound of rock drums in the big space (local artists Let Fall the Sparrow), and they had Mark Wilshire in engineering the Cypress String Quartet; he gave a ringing endorsement, which bodes well for some of the scoring work they hope to pick up.

The goals are lofty but completely realistic in and around 25th Street these days, with an eye on the local community and plans to reach out to artists and engineers across the country. “I’ve grown to believe over the years that a great-sounding room can accommodate all genres of music,” Manzella concludes. “Rock, pop, indie, jazz, classical, hip-hop. You may have to adjust a few things, but the room still functions as a room. And this is a great-sounding room.”