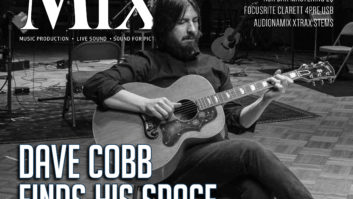

In order to truly “come back home again,” in a manner celebrated in story and song, you have to first truly get away. You have to make a big break, not a parallel move. You have to challenge yourself and the way you live, to find the way you want to live. Then you can go back home at peace, whether personally or professionally, metaphorically or literally. For producer/engineer John Davenport, “coming home” meant all of the above, and he now sits, in his mid-50s, in his dream studio on 10 acres of a 500-acre family farm, along the Deep River in beautiful North Carolina.

From the time he left home at age 18 until he returned and eventually built this month’s cover studio, Davenport lived a Walter Mitty-esque life that began in the heart of the 1980s New York City recording scene. At the time he had just graduated from a military academy and was debating enrolling in the U.S. Air Force Academy. He took a two-week trip to New York that summer to stay with his sister and he stayed for 10 years.

“On my second day of visiting my sister, she said that she and some friends were going to a studio that night at 10 o’clock and asked if I would like to come along,” Davenport recalls. “That was Chelsea Sound, and I was just smitten. I kept coming back, and then they started using me as a gofer, and I eventually was asked to plug stuff in. I was taught by a great engineer, Bradshaw Leigh. I stayed the summer and just loved it.”

Chelsea Sound did jingles and voice-overs, as well as music, and one night, when the engineer had to leave at 1 a.m., they threw Davenport into the hot seat on an Elliott Randall session. Around 5 a.m., he accidentally erased half the tracks. “That was the night I became an engineer!” he laughs.

When that summer ended, Gus Skinas offered Davenport a job as an assistant maintenance engineer at nearby Secret Sound. He taught him to solder, work with transistors and align tape machines. He assisted on sessions, too, using tape loops for delay, learning the MCI console. The studio was busy, with the likes of Spyro Gyra, Evelyn “Champagne” King, The Spinners. It was the height of disco, and he was trained old school, making $180 a week having a ball. Then they had to let him go—he was making too much as an assistant. Skinas told him to call Ed Germano at The Hit Factory, who was looking for an assistant.

“What an incredible time,” Davenport says. “Eddie and Troy Germano were very nice to me. There were artists coming in and out every day. I was 21 in New York City and riding up the elevator with Michael Jackson. John Lennon was doing Double Fantasy there when I was hired. Every day and week was a new thing. I was an assistant for guys like Chris Kimsey, spent a lot of time with Michael Kamen. He was a genius. I worked with him and Jimmy Destri from Blondie. Chris Lord-Alge, Tom Lord-Alge, Bob Clearmountain, Ed Stasium, Frank Filipetti, Eric Thorngren on a Robert Palmer record—I was in the room with the best of the best.”

He spent two years as an assistant on Bruce Springsteen’s landmark Born in the U.S.A.—75 songs over the course of two years, with Chuck Plotkin and Toby Scott and the hardest-working man in show business. It is a time he treasures. Then, just as he was getting more engineering work, including a co-credit on the Rolling Stones’ “Undercover of the Night,” he up and left New York and headed to San Francisco.

What followed was a seven-year odyssey that took him from the Bay Area down to a ranch in Big Sur, over to Hawaii for a while and some work in a dive shop, a year-plus as an independent engineer in Japan, a month-long trip to Belize that turned into a year, before he finally decided to come back home in 1997 and take care of the family farm, while helping his brother run the 100-year-old family food distribution business. He was there during an explosive growth period. He still dreamed of his own studio, an intimate creative getaway.

The idea for the studio was actually born in 1997 while Davenport was building his Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired home on the property. All 60-degree angles, local materials, “part of the hill, not on the hill.” He had been doing some engineering in nearby Chapel Hill at Wes Lachot’s studios, and asked the engineer/studio designer to come out. Their design aesthetic was completely in sync. Lachot drew up plans based on a hexagonal, honeycomb geometry.

But it was too soon. Davenport took some time off to raise his son and grow the business. When his family sold the company in a few years ago and he got his first check, the first thing he did was call Lachot and revive the project. Lachot went back to his original hand-drawn designs, spent a week trying to come up with something different and better, but couldn’t.

“He had built this house on a honeycomb geometry, and it was really the start of the hexagonal geometry I base a lot of my studio designs on to this day,” Lachot says. “I had a Eureka moment about 20 years ago, when designing this studio. It all begins with the equilateral triangle at the listening position. Then you try different angles for the walls to get the widest sweet spot. I found that the hexagonal geometry works best, a series of six 120-degree angles, where all the reflected sound is angled to the back wall. You don’t have to get rid of that sound, you don’t have to over-dampen it. You don’t want to soak it all up or the room will sound sterile. The rear three sides of the hexagon are diffusive at high and mid-frequencies and absorptive at low frequencies. That’s where we go to the slotted Helmholz resonators, in addition to the full-range basstrapping overhead. Then behind the Helmholz resonators there is a system of tuned membrane traps that are tuned to specific frequencies based on the engineer’s position.”

The studio is not large, roughly 1,200 square feet in total. But it has an intimacy and relaxed feel, with a 20-foot-wall of glass overlooking the river, which is meant to inspire. The control room employs ear-level monitoring out of ATC SCM 200 mains and ATC SCM 450 nearfields, and it’s centered around a custom API Legacy Plus console with Vision software, selected for its analog punch (and because Davenport remembers the API on the sixth floor at Hit Factory with fondness) and configured for the way Davenport likes to work, including a patch bay to the right of the 24 faders. He asked for graphic EQs on 1-8, and parametrics the rest of the way. “It just sounds great,” Davenport says. “You start out with an analog microphone, why not have the best analog console.”

The ceiling clouds of the control room and live room are also based on equilateral triangles, employing trapping and absorption. “Every other triangle is fabric-covered, just standard fiberglass bass traps,” Lachot explains. “The wooden ones have a series of holes developed from the math RPG developed for their BAD panels. Peter [D’Antonio] developed them about 1999, and we use RPG BAD panels extensively, in all of our studios. But they are usually square panels, and I didn’t think it would be aesthetically appropriate in the room to use the square pattern of holes. We took Peter’s math, and I skewed it to the hexagonal geometry, so it’s something of a collaboration.”

Both rooms also have a soffit ringing the area, which serves as a bass trap as well as practical and aesthetic purposes. The live room includes a fireplace made from bricks by a local brick company three miles up the road. Lachot likes a combination of reflective and damped surfaces, which leads to the windows.

Ten 2-foot windowpanes run nearly the entire length of the studio, offering a one-of-a-kind view. A series of 10 rotating acoustic panels, absorptive on one side, diffusive on the other, allow for variable acoustics—quadratic diffusion via RPG FlutterFree T, with fabric on the reverse. An iso booth fills one corner. A couple of echo chambers sit in the basement. The acoustic build-out, as usual on Lachot designs, was by the master Tony Brett of Brett Acoustics in Durham; the A/V wiring, BNC and Cat-5 throughout was by Thom Canova of Canova Audio.

While the studio is for hire, there isn’t really a rate card. It has accommodations and amenities to rival any four-star hotel, but it isn’t really a residential facility. It was built with Davenport’s aesthetic in mind, for the way he likes to work. It’s for friends and family and those looking for a creative getaway. He has produced local bands and hosted artists who won a spot from fundraisers he helps to organize. He also has produced three short films directed by Monica Tidwell and has an eye on multimedia production.

But most of all he likes to get away from the stress of the city life and the notion of a sterile studio. He likes to ride his ATV on the property and fly his drone over the river. He is a rancher, a farmer, a businessman, a studio owner, a producer, an engineer and a dad.

And he couldn’t be happier at home. Making music.