Pictured are lead audio engineer John Stoll and audio engineer Elizabeth Weissinger. The two smaller machines (stacked vertically in the rack) are Tascam MX-55s. The larger machine is the Ford/Philco 30-track 1-inch Soundscriber.

Photo: Lauren Harnett/NASA

John Stoll has an audio job that’s never going to earn him a Grammy or let him spend weeks on the road staying in fancy hotels in exotic ports-of-call. At parties, he can’t say he’s worked on projects involving Bono, Jagger or Jay-Z. But Glenn, Shepard and Armstrong are another story, and they are part of the story Stoll is helping to tell America through his tireless work for NASA the past seven years.

As lead audio engineer at NASA’s Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Stoll has spearheaded an exhaustive (and exhausting) effort to digitize many thousands of hours of recordings of manned U.S. space flights, from the early ’60s to the present. Further, he’s been responsible for posting the fruits of his labor on the Internet for all the world to hear, on Archive.org. From pre-launch communications, to thundering blast-offs, to in-flight conversations on the spacecraft and with Mission Control, to splashdowns and landings, there is a fascinating and comprehensive audio record of the U.S. space program, captured on a nearly unthinkable number of tapes (and disks) in a wide variety of formats.

“When I came here [to JSC], we had a vault full of analog reel-to-reel tapes that starts back at the very first manned Mercury flight [by Alan Shepard in 1961] and goes up to the present day on the Space Shuttle and the Space Station,” says Stoll, a native of Harlingen, Texas, who got his start in audio running sound for the band he was in and got a more formal audio education at South Plains College in Levelland, Texas, before landing his first job at JSC in 1997. “We also had a big box of microfiche that had scanned transcripts of everything everybody says from all the early missions—they stopped doing the full transcripts in about the Skylab days and early Space Shuttle days, for budget reasons.

“I thought it would be great to have all this material more accessible to the general public and for everybody from researchers to students, and with Internet speeds increasing everywhere real quick, it seemed like it might be possible,” he continues. “To me, it’s all about transparency and availability. This is a national resource.

An overall view of the Shuttle (White) Flight Control Room (WFCR) in Johnson Space Center’s Mission Control Center (MCC).

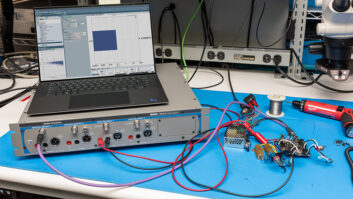

“So we got all the microfiche transcripts scanned into OCR [optical character recognition] PDFs and stuck all that up on Archive.org, and those have been tremendously helpful to many people. Then I started taking a look at the audio, and a lot of it is ¼-inch 2-track, some of it is ¼-inch full-track. Some of it’s 1/2-inch 8-track, some of it is ¼-inch 7-track. One format is 30-track 1-inch tape. So it’s all over the place and it’s been a challenge to work with all these formats.

“Media and schools and other groups were always asking us for audio clips—maybe a quote they were looking for—and in the past the way we would fulfill those requests is we’d use the microfiche reader to find the quote and then extrapolate that to a tape. We’d process the clip and send it to them and they’d usually use it once, and then that work was gone. What I wanted to do was digitize the whole clip and put it in a public place where everybody could find it. Now, I can send a link to whoever’s requesting, for whatever they’re requesting, and they can find it in the PDF file and go get the WAV file from Archive themselves.”

Some might be surprised to learn that tapes from the early years of the manned space program—the Mercury and early Apollo days—“are the healthiest ones we have; solid as a rock,” Stoll says. “It’s pretty much all ¼-inch 2-track of varying sizes of reels; nothing was standard.” One of the tape machines in that era was a ¼-inch 7-track Ampex SP-300 instrumentation recorder, which didn’t have a particularly good fidelity “but was a way to multitrack in the early days,” Stoll says.

Even though Stoll says that NASA was generally good about labeling and storing tapes, the archiving and digitizing job has involved some sleuthing along the way. Former NASA Flight Director Gene Krantz found a large batch of old tapes—some unmarked—underneath one of the consoles in the Mercury Control Center (in Florida) right before it was torn down. He brought a bag of these tapes to Stoll in 1998 and “we had to sit down and listen to some of them and figure out from the comm what [mission] it was from. Fortunately, he knew what most of them were. But I do still have a box of mystery tapes here at JSC. For one thing, there were a lot of simulations done, and if those were recorded, it sounds exactly like a mission. In fact, the Apollo 1 tragedy [in which three astronauts died in a capsule fire on the launch pad in 1967] was a simulation. There are also different ways of labeling and even different ways of recording time: GMT [Greenwich Mean Time] is standard, but some were labeled with GET—Ground Elapsed Time starts at zero when a mission starts, so you have to go back, find out exactly when it launched, and make a formula to figure out where you are on the tape.”

Some of these early tapes were also quite brittle. “Many required dozens of splices just to play,” Stoll says. Still, they produced a bounty of “lost” audio history, including an early Redstone rocket test flight and the original recording of the flight of the space chimp Enos, in the pre-Mercury days.

The most unusual recording format NASA used came during the Apollo days, when it employed a pair of custom 30-track recorders at JSC. “Only two of them were ever built,” Stoll says, “and one of them is still here at NASA; the other was used as parts to restore the one that still works. They’re all tube-driven and if you look underneath, everything is point-to-point hand-wired on turret boards. It’s amazing to see how it was built. They ran at 15/16-inches per second, which is half the speed of a cassette, and one 10-inch 30-track reel of tape held 14 hours of mission.”

Why were 30 tracks needed? “There was a lot to be recorded! The cut sheet of what they would actually record would change at different points in the mission because there are different people here for launch and on-orbit and landing operations. They would record the air-to-ground channel that went up to the capsule; the flight director loop, which is the main comm loop that goes on here behind the scenes—anybody who has seen [the film] Apollo 13 will know what that is—and also a ton of other back rooms. There’s a room that does the environmental support systems of the spacecraft, a room that does the communications with the craft from the Earth to the ground. There are people who do tracking and pointing and attitude control. Each of these disciplines has their own backroom communication loop, so all those are recorded simultaneously.

The Apollo 11 launches on July 16, 1969, bound for the first Lunar landing mission.

“Back in the middle to late ’70s,” Stoll continues, “there was a transfer of most of the [30-track] material to ¼-inch and we shipped off the original 30-tracks to the National Archives, so they could be kept for safekeeping there. But only the air-to-ground channel and the public affairs commentary channel were transferred. There is actually an effort right now to partner with some people to get those 30-track tapes out of the National Archive and digitize them in their entirety. Of course we would need the machine to do that. As it is, you can only play one channel of audio at a time and the way you select the channel is there’s a little rotary knob on the front of the head. As you can imagine, with 30 tracks on a 1-inch tape, getting on the track you want is really almost impossible. But we’re working with someone to get a custom head built so we can take all 30 tracks out, digitize them and go from there. Each tape gives you 30 14-hour-long WAV files, one per track. That’s a lot of data. And we have probably 150 of those 30-track tapes here that were not transferred off to ¼-inch, so that’s our mountain to climb here.”

By the time we get to the Space Shuttle program (technically known as the Space Transportation System) in the early ’80s, the 30-track was long gone, replaced with more conventional multitracks, including half-inch Ampex 8-tracks at JSC to capture just the air-to-ground, the flight director loop and the public affairs commentary. “We started paring down what we recorded here,” Stoll says.

Unfortunately, many of the later tapes have proven to be more problematic for digital transfer. Stoll notes, “Starting in the late ’80s, and especially the early ’90s, I pull those tapes out of the vault and they just don’t play. The problem with the tape is with the backing, not the audio side—the tape formulation changed. So they have to be baked. You read the recommendation, or maybe you learned in [recording] school how to bake a tape: 14 to 48 hours at 130 to 140 degrees, let it cool all the way before you play it. Well, that doesn’t work for these tapes. Our vault is in Houston—in Clear Lake specifically, which is near Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico—so its super humid and a lot of these tapes have mold on them. They’re all stored tails [out], so in order to get these things to play I have to bake them for about two weeks at 145. I pull them out of the oven and they’re still at full temperature, I get Pro Tools running, I stick ’em on the machine and hit Play and play them in backwards; then I just reverse them, because if I wait for them to cool, they won’t play. They’re so sticky it’s amazing. So we’re breaking all the rules in how to do it.”

Stoll has used a few different archiving formats, including SADiE and Nuendo, before Pro Tools. “From the beginning I’ve been going 24-bit, 48kHz PCM WAVs,” he says. “I guess I could capture them at 96k, but the file size gets so big for I’m not sure what gain. But it’s the processing power of computers—and specifically native processing—that really made it seem like we could do this now.” Pitch-changing plug-ins have allowed him to deal with speed irregularities in the original tapes, and other in-box processing helped him tame some of the more egregious hums. He’s even been clued into some pitch issues by commenters on Archive.org: “The beauty of having the audio there is that the peer review process is now worldwide. I appreciate every comment I get.”

Even with all the work that has been done to get so much material up online the past several years, Stoll estimates that only about 35 percent of the available material has been digitally archived. “Apollo was maybe 10 years and the Shuttle ran for 30 and had more and longer missions,” Stoll says. “I’ve barely started touching into the Space Shuttle audio, and a lot of those tapes are in bad condition. The quality of the recording is better, but the tape formulation really drops off, so that’s going to require a lot of time.” And this has never been the main part of Stoll’s job. Rather, he’s fit it in around other work he does around the JSC involving NASA broadcasts and media outreach.

John Glenn

For the moment, at least, Stoll is dealing with a finite collection of space flights that need archiving. The Space Shuttle flew its final mission in 2011, and there are no manned space flights planned for the near future. He is understandably wistful about what truly is the end of an era: “I was sad to see the Space Shuttle end. It was very big part of my life. When Space Shuttle was flying, we were broadcasting 24-7 [over the NASA TV cable channel], we were doing press conferences, briefings, interviews with people on the ground. I was fortunate enough to be able to hook up President Obama with the Space Shuttle [on the final flight]. That was a thrill. The Space Shuttle was a great, great machine.

“Now the attention shifts to the Space Station for the next few years. We [NASA and its international partners] stopped building it, but we’re utilizing it and there’s a lot of serious science going on there. The science coming back from the Space Station is going to change the world.”

Meanwhile NASA’s presence on Archive.org continues to grow. You can give your subwoofer a workout replaying a Saturn 5 rocket launch or drift for hours along with astronauts as they orbit the Earth and talk about what they’re seeing and doing. Stoll has also helpfully extracted some of the more famous moments into short, easily findable clips—“That’s one small step for man…” “Houston, we’ve had a problem…” and other NASA Greatest Hits. A good place to start is the homepage: http://archive.org/details/nasaaudiocollection.

Asked if there’s an audio moment that he finds particularly inspiring, Stoll doesn’t hesitate: “I can’t listen to John Glenn’s first launch without getting goose bumps. It still excites me. I stand up when I listen to it; it’s a reflex. It’s just so cool what they were able to do, and it was truly on a shoestring budget in those days, and these old recordings really get those across.”