The 47×36-foot, 22-foot ceiling “Big Tracking Room,” attached to the Neve room pictured on this month’s cover.

Photo: Alan Esparza

Vibe is one of those versatile descriptors that can mean nothing or everything. It can be used to describe a person, place or thing in the generic, or, when attached to a modifier, become more specific, as in a “funky, New Orleans vibe.” It can be attached to an event, like a Clive Davis after-party, or a unique piece of art, an individual rock star or a scene a la Brooklyn. It can be so overused that it loses its luster, yet can sometimes be the only word that fits. At its simplest, it describes a moment in time. At its most complex, it describes a total experience, one that is just there all the time. Sonic Ranch has vibe—all-caps, boldfaced, italicized Vibe.

It starts with the structure itself, a 1930s hacienda with foot-thick adobe walls and exposed rounded logs for beams, from the nearby Lincoln forest. Then it climbs up the walls with a mishmash, juxtaposed explosion of fabrics from around the world that unexpectedly works throughout the complex, broken up by numbered lithographs from the likes of Dali, Miro and Chagall, along with an eclectic collection of art from India, Colombia, Argentina, Mexico and the American Southwest. The vibe continues outside in the three-sided plaza, tile-framed pool, 80-year old grape vines, 2,000 acres covered by pecan orchards, and star-filled, big-sky country, at a Border-bordering nexus of Tex-Mex culture.

That’s the environment, a distraction-free destination studio complex 30 miles east of El Paso, with eight guest rooms in the hacienda, with 20 more in five additional houses on the property. Since opening with a single A room in the early 1990s, its evolved into a five-studio, turnkey operation, songwriting to mastering, under the direction of owner/director Tony Rancich.

A West Texas native, Rancich is the quiet creative force behind Sonic Ranch. He jumped into music early, started recording at 15 and, after various incarnations, found his studio home on a ranch in the Rio Grande Valley. He is self-taught and well-versed in philosophy, psychology, art, wine, world cultures, and countless other topics. He also runs the pecan ranch and horse farm. He is the consummate leader-by-example, rallying all who work there to pick up a hammer, trap a raccoon or help cook dinner. The style choices and vision are his.

“In building out the studios, to me, the atmosphere and vibe was as important as the equipment and acoustics,” Rancich says. “It needs to inspire. All the rooms are different, so it has to do with mingling all these esoteric elements, from fabrics to lithographs to vintage consoles and outboard. Find the pieces, and find which pieces go together. As we put together rooms, there’s a lot of experimentation in design. It’s like tracking or mixing a song.”

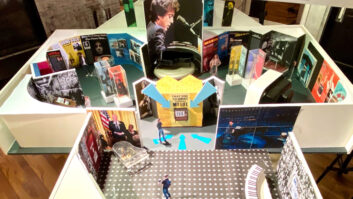

Adobe Tracking Room

Photo: Alan Esparza

Expanding the Vibe

In the beginning, the late 1980s, there was Studio A, Having outgrown his recording space in El Paso, Rancich found the current property, lured in by a wing of the hacienda that sunk a few feet into the earth and a few years later became Studio A. Producer Howard Steele, owner of Studio 55 in L.A., helped locate the SSL 4000 Series E/G (Black Series EQ), two large iso rooms were added, and by the early 1990s Sonic Ranch was in business. It remains the favorite spot for many repeat customers.

Those early days were mostly local and regional acts. Then a few well-known British producers hooked in early, people like Stephen Short, Colin Richardson and Neil Kernon. Rancich credits their faith in the place and the clients they brought—most notably Kernon and Short, who flew in more than 150 projects from around the world—with making the later expansion possible. It was a lot of heavy music, rock music. At the same time, inquiries began to come in from Mexico, particularly Chuy Flores bringing in the band Jumbo and many others. The room stayed busy; there was even demand for more.

One of those clients, in 2001, was Marco Ramirez, who was producing and recording his own band. Ramirez had been a freelance engineer and artist in Mexico since 1985, working with many top acts, but he had never seen anything like the gear and environment at Sonic Ranch. “I had never been in a big studio like this,” recalls Ramirez, who never left after that initial session and now serves as studio manager and mastering engineer. “It was a dream, all the equipment I would read about. I always dreamed about that sound on the vocals, and it was the first time I had heard something that good.” Ramirez would go on to record three projects for Ministry and two by the Revolting Cocks, among countless other records. He’s also proven instrumental in connections throughout Latin America, from Mexico to Colombia to Argentina.

By the time Ramirez came onboard as house engineer, it had become clear that there was enough demand to justify expansion. Rancich brought in noted designer Vincent Van Haaff, whom he had first hired to redo A’s control room in 1998, on the recommendation of Joe Chiccarelli. There was no linear plan in place, but one did come together through a series of synchronous events, starting with demand for a larger tracking room.

By 2000 work had started on the Neve studio (in a separate structure, 100 feet from the hacienda), with room for up to 65 pieces in the vaulted-ceiling, variable-acoustic live room and a spacious, comfortable control room (with two iso booths!), pictured on this month’s cover. The vintage 80-channel Neve 8078, with 31105 pres/EQs, dates back to the West Coast Motown studio, later to Madonna, then Yoshiki at Exstasy. Ramirez’s mastering room came online in 2002.

Adobe Control Room

Photo: Alan Esparza

Then in 2004, Rancich purchased a neighboring ranch, and with it a century-old adobe structure that today is, naturally, called the Adobe Studio, about a mile from the main house. Serendipitously, the 40-channel Neve 8088 from Dusty Wakeman’s Mad Dog Studios became available. In and around the same time, back at the hacienda, the in-house team, based on designs by Van Haaff, gutted the garage in the hacienda and constructed a mix room, with a 64-channel SSL G/G-Plus running at 240 volts.

There are either Augspurger/TAD or Tannoy double-15 mains in each of the rooms, and enough outboard gear to run another five studios, along with a large mic closet and a vintage instrument/amp collection to rival any, with a recent penchant for old synths. They have everything modern that you might expect, too.

“We had more demand than we had time for the one studio,” Rancich recalls. “So it became a matter of, ‘If we build another studio, will they come?’ I prefer the Ralph Waldo Emerson quote, ‘If you sharpen a knife, people who need a sharp knife will come.’ So it was a matter of building it out to what people wanted. Great vintage equipment is always in demand. And we realized there would always be a demand for a real studio with great rooms. But we had to make each room as good as the other ones. Different, of course, but just as good.”

Multiple Influences

Concurrent with the expansion of the space came an increase in the variety of projects. Heavy rock and Latin Christian turned into British, Italian, Argentinean, Colombian, Mexican pop and a noted uptick in American indie. On the day Mix visited, southern songwriter/artist Charlie Mars was in Adobe with Billy Harvey producing, Nina Diaz from Girl in a Coma was mixing with Manny Calderon co-producing/engineering, new singer-songwriter Sidney Wright was in the Neve room with writer/producer Stefano Vieni and engineer Alex Ponce, overseen by manager/producer Arthur Penhallow Jr., while engineer Yamil Martinez was working with Colombian Christian artist Alex Campos. The Dirty Heads, a reggae/hip-hop group produced by Rome Ramirez and engineered by Charles Godfrey, had just left. Most come together at breakfast, served to order by a wonderful cook, then retreat to their projects, bumping into each other throughout the days and weeks. Those who want to be alone can be.

Marco Ramirez’s mastering suite, which includes a rare, signed (!) Rupert Neve/Billy Stull Masterpiece.

Photo: Alan Esparza

“I love to take bands out of their comfort zone and their normality,” says British producer Jason Perry. “I like it to be like an adventure, something inspiring and different. Something that they’ll never forget. These are musicians, so the music is the easy part. Let’s make it special and get away to the desert, immerse ourselves in music, no distractions. Then the food, the heat, the insects, the sky, the desert sand, the pool, the buildings, and you’re right on the border of Mexico. There’s just an amazing clash of cultures there.”

That variety of artists and producers—from the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Charlie Mars and Sublime With Rome to Flogging Molly, Zoe and Whitey Morgan—coming into a common place certainly benefits the studio, as the best form of sales to date has been word of mouth. But the variety has also provided a true post-graduate, real-world education for assistant engineers, as they learn techniques and styles from a constant stream of visitors.

Charles Godfrey was working at Guitar Center when he was hired eight years ago as a drum tech, moved on to assisting, and recently engineered the Dirty Heads record, and he’s worked with the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, who have done two records at Sonic Ranch. He also produced nine projects last year. El Paso native Manny Calderon graduated Full Sail in 2008, then interned/assisted at Westlake in L.A. for three years before coming home to assist at Sonic Ranch. His first gig was Mexican super-act Zoe. His second project was a record for Girl in a Coma; last week he was co-producing GIAC frontwoman Nina Diaz on her solo project. He’s also worked with dozens of others. Sonic engineer Jerry Ordonez engineered the new Zoe record, and Zach Mauldin engineered projects for Bob Treachad’s Cat Food Blues label.

“They have an opportunity here to work with some of the greatest producers in the world, and they are all different,” Rancich says. “So you get to borrow from all of them and put those tools in your arsenal, so to speak. Now Manny, Charles, Jerry and Zach have these opportunities and are becoming formidable themselves. There’s a great community here, and people all help each other. Artists end up writing with each other, or meeting a new producer. Things that get put together here tend to then take on a life of their own.”