The upstairs control room, centered around a restored 1978 MCI JH428 console.

Photo: Elizabeth Streight

It doesn’t take much sleuthing to find out the basis of Chris Mara’s recording philosophy. It’s right there in the name of his Nashville studio, Welcome to 1979. It’s in the MCI tape machines that ring the control room awaiting restoration and sale, in the lathe he purchased recently because he wanted more consistency in his vinyl releases, in the layout of his 7,000-square-foot, band-first facility, and in the Recording Summits and Tape Camps he hosts. Of course he has Pro Tools, but he’s a decidedly, unabashedly analog-tape kind of guy.

But his is not some all-consuming nostalgia story, or some analog purist tale. The emphasis on tape-based tracking/mixing was originally borne of necessity as much as ideology. Later it became a selling point. Mara doesn’t eschew the sound of digital recording or ignore its benefits. But, he says with a laugh, “We do unhook our tape machines to hook up Pro Tools.”

The Road to 1979

Mara arrived in Nashville as a 19-year-old in 1995, having grown up in very-small-town northern Wisconsin (“the nearest stoplight was 15 miles away”) and cutting his teeth in live sound as a 16-year-old running live sound for a rock band. The nearest big city was Minneapolis. He did sound and lights for opening acts in small clubs, and wanted to learn more about touring. He enrolled in studio recording courses at a community college to glean what he could about live sound, then tagged along with a roommate to Nashville, where he found himself “amazed by the number of studios, so unlike Minneapolis.”

He got an internship right away at The Recording Club in Berry Hill, and soon was working sessions as an assistant. He met a couple of engineers and producers, and began working at studios all around town. The 1990s were a different time, very busy for assistants. He credits that time as his school. So many teachers, in so many environments.

“Marty McClantoc was one of my mentors,” Mara recalls. “I‘d say about 80 percent of the techniques I learned from him I still use today. He came from Muscle Shoals, so the people who taught him essentially taught me. I was lucky to be last in line of a very good gene pool there. How to do a B3, a piano, this matters, this doesn’t matter…Marty was real hip on staying in your role in a session. If you can’t be a good assistant, then you won’t stick around to be a good engineer. I learned how to behave, how to maneuver a session.”

After three years of strictly freelance assisting, Mara began engineering about half the time, going out to find rock bands and convincing them to work with him because he was fast and had access to studios for decent deals on weekends, late at night, pay as you go.

At a Welcome to 1979 Producer/Engineer Summit, panelists, l to r: Mitch Easter, Todd Robbins, Neal Cappellino and Larry Crane.

Photo: Elizabeth Streight

“I’m engineering everything I can,” Mara recalls. “Taking anything. Actively seeking more independent rock bands and having some luck with it. But I’m losing more and more work to the money issue—I had to go in and rent a studio and get my rate on top of it, when a band could go to someone’s home studio for half the cost. A few years of that go by and I start to think, ‘If I had a studio, what would I want?’ I want a lot of square footage. I want ground-level load in. I want a big control room. At this point we have a two-year-old boy, my wife is pregnant, and I say, “Honey, I want to get a studio.” [Laughs]

Space and Vibe

He had already been thinking about a name and a philosophy. He shied away from “Tape” or “Analog.” When he said, “1979,” it had a ring, and he liked the word “Welcome.” Later he would get calls and emails raving about that year as a hallmark of recording. At the time, it just sounded good. And his philosophy? He priced out a fully-blown Pro Tools HD rig and simply couldn’t afford it. Plus, he had a solid MCI tape machine and a couple racks of gear. He would be analog. He still didn’t have a studio.

If it sounds that innocent, it’s because it is. Much of Mara’s, and his studio’s, development has been unplanned, driven by both experimentation and a frugal business sense of working with what you have. While on the way to his bank one day, Mara passed a building with a For Sale sign, as he had many times before. This time he contacted the owner, and over the next six months talked him into a two-year lease on the front 7,000 square feet, arguing the financial benefits of leasing to a studio owner in a down real estate market. Seven years later, he’s still there.

“All the wood was here,” Mara says. “It was built in 1954 as a record pressing plant. Gorgeous wood. Two stories with lots of rooms. A perfect floor plan. Originally I thought I would be building out into the warehouse, but a band came in and said, ‘Wait, this feels good down here on the floor. Why don’t you go upstairs for a control room?’ It was perfect. It’s a little weird, but it was a fast avenue toward making money and it sounds great!”

Over the ensuing months, Mara continued engineering by day and night, wiring and painting and imagining his new place in his off-hours. When it came time to move in equipment, he traded a band studio time for grunt labor, hour for hour. The band got two days of recording. Mara got his fridge, piano and old-new console moved into the upstairs, 1,200-square-foot control room. In what has become a theme, Mara stayed within his means, purchasing an MCI JH-428 console from friend and confidante Randy Blevins, unrestored. Mara would do the restoration.

His first gig was a rock band, so he made sure that he bought five sets of headphones and mic stands and 15 mic cables. That gig would finance the next purchase, the next set of headphones. “I think bands get that,” Mara says. “My rates are fair, my overhead is low, because of the sweat equity.”

Over the years he has enlisted the help of friends and experts in listening to the room and making improvements. Acoustician Steven Durr has been a key consultant from the beginning, a couple of years ago helping him with isolation and transmission issues in the main tracking room ceiling. But by and large, the space has a sound, a vibe, a unique character, one he didn’t have to mess with.

A few of the MCI tape machines, 1978-87, restored by Mara Machines.

Photo: Elizabeth Streight

Grow As You Go

Mara knew from the beginning that there was no business in booking time alone; there are simply too many good facilities in Nashville at all levels of the food chain. He charges a single day rate, same for all customers, regardless of how long a booking. It has helped him and hurt him, he admits, but he’s sticking to it. He believes in his fair rate. Then again, he has other revenues; from the beginning, Welcome to 1979 was meant to be more than just a studio.

“I had always wanted to have a tape camp,” he says. “You get 10 people in for a weekend who pay x amount of dollars, make it affordable, get a band in and just talk about tape and the differences between tape and digital. And how they are more similar. Show people how to comp on tape. Then record a band and have fun doing it. We did that the first year, and we’ve now done dozens of them, even in other cities.”

Also in year one, Mara started an annual Recording Summit. Having been to a number of national conventions and regional events, he wanted to present his take, without trade show booths or apparent conflicts of interest. It sells out every year, with a max 60 people gathering over a weekend in November. Hand-picked panelists are paid, Twitter is turned off, people are free to mingle and network and say what they feel. Face to face. In small groups.

While those expansions were conscious, Mara backed in to perhaps his most unexpected enterprise, Mara Machines, after he started receiving calls with people asking where he got his tape machine, how could they get one. After four or five inquiries, he started thinking that he could sell these. He bought one, restored it, sold it, bought another, restored it, sold it. Six the first year. Thirty last year. Eighteen by April of this year. All MCI machines, from 1979-1987. Pete Townshend has two 1-inch, 8-tracks; there are now about 100 around the world. Vintage King is his exclusive retailer. For Mara? “That money can buy headphones and mics.”

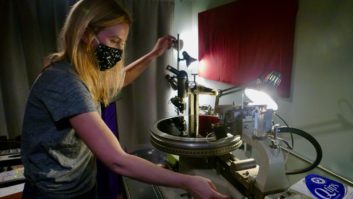

Mara and his crew do the troubleshooting and most hands-on repair, hiring out to Steve Sadler for component-level work and final fixes. Mara is driven by the theory of how things work, inherited from his father, an electrician and it’s served him well. When he discovered that half his mixes sounded great on vinyl and the others “sounded like shit,” he started to wonder why, so he called up A-level mastering engineer Hank Williams, at the time an acquaintance and now a friend, and asked why.

Further inquiries, coupled with a suggestion by mastering engineer Eric Conn that he should get a lathe, soon led Mara into record cutting. “At this point I’m buying a lot of gear on a regular basis, and buying a lathe was the most difficult thing I’ve done,” Mara says. “They’re rare. And the people who deal in them also cut lacquers, so instantly you’re getting the leftovers. Hank was so kind that he let me reply to some of these guys with him cc’d on the emails, and you would not believe how nice people get when there’s an expert in the email!

Mara found a lathe, Chris Muth restored it, then Williams came over and spent three weeks with Mara and Cameron Henry, who had been hired but had never cut a record old-school. “Hank didn’t care,” Mara recalls. “I didn’t even know how to turn the lathe on. Swear to God. But Hank came over and it was like Karate Kid. We spent two days talking about records, looking at records, before we ever even turned the lathe on. Cameron and I both know the theory of operation, how it works, how it’s supposed to react. And now Cameron is one of the finest cutters in the country.

“I’ve been taught by the smartest people on the planet,” Mara says. “Randy Blevins taught me a ton. John French. Mike Spitz, Tom Beaupre, Steve Sadler, Ben Surratt. All these guys taught me so much about the theory of operation of a tape machine. Others taught me about the lathe. If you know exactly how it works, then you can figure out why it’s not working.”

Now entering its seventh year, Welcome to 1979 is much more than just a studio. It’s become the nexus of a small but mighty community of tape lovers, recording experts and bands that want to rock out. A couple of years ago, with small children and a good, though uncertain job, Mara’s wife, Yoli, joined her husband and now handles the business side. Thinking that they were downsizing, they soon found that business had never been so good.

When you build as you go, within your means and from the ground up, with commitment to your passion, good things can happen. Whether it’s 1979 or 2014.