Disney magic still manages to bring out the kid in everybody, including the veteran creative and production personnel for the animated feature Treasure Planet. While you might expect the seasoned pros to take a blasé approach to their work, the opposite was true; all involved labored to outdo themselves to bring the modern-day version of Treasure Island, Robert Louis Stevenson’s beloved pirate adventure tale, to life. Of course, it didn’t hurt that Planet takes the action into a universe full of alien worlds and galactic wonders.

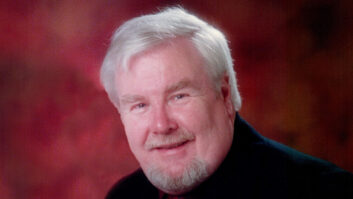

“They raised the bar again on this one with the animation,” comments Terry Porter, dialog/lead mixer on a team with Dean Zupancic, sound effects, and Mel Metcalfe, music, with the dub taking place on the AMS Neve DFC at Disney’s Main Theatre. “It’s a combination of 2-D and 3-D animation, and the picture is spectacular. Of course, that makes the bar go up for audio, too. The soundtrack has to follow with the same degree of quality and care or it will feel detached from the picture. Directors Ron Clemons and John Musker [Aladdin, The Little Mermaid] are veterans here at Disney. They command expertise from all of us. The picture editor, Michael Kelly [Mulan, Rescuers Down Under], is also extremely meticulous. They all have very high expectations. That puts a lot of good pressure on us.”

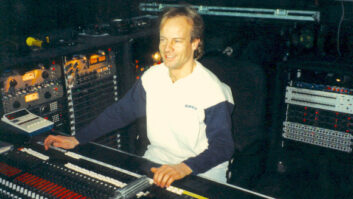

A major challenge was melding elements of the classic seagoing story with a large dose of futuristic action-adventure. “Throughout the project,” says Academy Award-winning sound designer Dane Davis (Danetracks owner, The Matrix, 8 Mile, Bound), “the directors maintained the concept of a 70/30 split — 70 percent familiar, traditional sounds and 30 percent exciting, fantasy-based sounds. We constantly strove for a balance between them to create an ‘antique future.’”

For example, pirate Long John Silver’s ship — a creaky, old Spanish galleon with masts, sails, rigging and rope — floats through space powered by solar sails that crackle and glisten with electrical energy as they absorb light to power the plasma rocket engines. “It creaks like a traditional tall ship when it turns or lists,” Davis says, “but it’s floating through a vast space ocean. It couldn’t sound like water, but it required the emotion and energy of wind and surf. Familiar and exotic at the same time.”

To create the sound for Silver, a cyborg with a mechanical prosthetic arm, Davis’ team scoured hobby shops and junk stores for antique windup toys and old spinning mechanisms. “We were able to manipulate those sounds to achieve the sophisticated end result we wanted,” adds Danetracks’ sound designer Rich Adrian, “but we purposely used unsophisticated sources to avoid sounding slick or sci-fi.”

Silver’s shape-shifting pet, Morph, got an even more organic treatment: “His molecules are constantly moving and rearranging,” Davis explains. “I used Jell-O in my hands to create movements, then digitally stretched and particalized the sounds to take it a bit out of our world. To integrate his movement and voice, we created vocal components using my voice through a mouthful of Jell-O.

Morph had to sound believable as an otherworldly creature, without coming across synthetic.”

For most of the other dialog, a traditional approach prevailed, with clarity being the goal. “We did some experimentation,” notes Porter, “especially with Ben the robot, a comic-relief character voiced by Martin Short. But everything we tried affected his comedy. Sometimes, when you start altering voices you lose emotion, and the last thing you want to do in a story like this is affect performances.

“I had 40 or 50 tracks of various voices — backgrounds, crowd and specific people,” he adds. “The quantity wasn’t as complicated as just getting a balance. I had to keep it lively and busy, without disrupting the storytelling aspect or obscuring the dialog, which you really don’t want to do in animation. In live action, you have a visual that helps you understand the dialog. With animation, even when the sync is incredible, you don’t quite have that. You have to ensure that the dialog is crystal clear.

“We were also fortunate that [composer] James Newton Howard really understands the storytelling aspect of Disney animation. He wrote music, beautifully recorded by Shawn Murphy, that worked in and around the dialog, so we weren’t constantly fighting busy music under important dialog.

“All the players were there to create a great soundtrack,” Porter concludes. “Schedules are never carte blanche, but Disney Animation always allows us the time to do it properly. They expect a good soundtrack, and I think we really delivered it on this one.”