Canadian film composer Mychael Danna has invented a highly diverse career for himself. Because most of the films Danna works on delve into intense feelings and states of mind that require equally enigmatic musical support, his scores rarely meet conventional Hollywood expectations.

“I think filmmaking fulfills a lot of different purposes,” Danna says. “There are movies where people really want to go to the theater and just see [and hear] something that they expect. There’s a certain comfort in that predictability. And there’s nothing wrong with that. That’s one genre of movie-making, and it’s a pretty big one. But there are other things that films can do, and that’s where I spend most of my time, [with those] other kinds of films.”

Those other kinds of films span a wide range, from the fascinating stories of director Atom Egoyan — Danna has scored all his feature films, including Exotica and The Sweet Hereafter — to Mira Nair’s erotic Kama Sutra and Joel Schumacher’s edgy 8MM. In scoring Ang Lee’s short BMW film Chosen, Danna composed a baroque/Tibetan score for baroque orchestra, a heady challenge he relished. Such eclectic, arty choices have allowed the Toronto-based composer to indulge in exotic explorations, which seems natural because he has a composition degree from the University of Toronto and some background in ethnomusicology.

“I’ve ended up [finding] that I’ve been able to work with different kinds of music,” he observes, “from Moroccan music in 8MM to American old-time music in Ride With the Devil to European medieval and Persian music in The Sweet Hereafter. The Ice Storm had gamelan as well as Native American [instruments]. Mira Nair’s new film, Monsoon Wedding, I recorded in India. The film I’m working on now [Atom Egoyan’s Ararat] is taking me to Armenia. I’ve just never felt that there was any reason to be limited to choosing Western orchestral music to score films with. Not only can you expand that into different places to draw from as your musical source, but also different times.”

While many film composers work intensively in home or personal studios, Danna uses his to flesh out his compositions before recording and mixing elsewhere. His films usually require him to record musicians in various international locations and then bring back the results to exploit further.

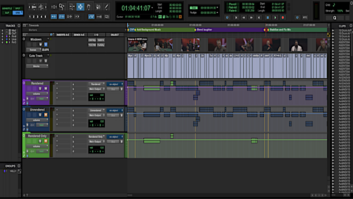

“For this project in Armenia, I’ll be recording [musicians] into Logic Audio, and then there will be a lot of manipulation of the audio files,” explains Danna. “In fact, that’s almost where the writing will happen after I record, because they’re folk musicians. I generally tend not to throw scores in front of folk musicians, although I did on Monsoon Wedding. I wrote out everything in India earlier this year, and then we recorded into Pro Tools in Bombay and just tracked it like a normal recording session with each instrument coming in separately — recording sitar, recording bansuri — one instrument at a time. They were just playing from scores, so I already knew exactly what I wanted and where I wanted it.

“But this film has a very Armenian kind of theme, so the idea is to weave a tapestry out of folk songs and melodies that will be played by folk musicians,” he continues. “I’ll be taking what I find and going with that. I’ve done a lot of research into Armenian music, so there’s certain folk songs I know I want, and there are certain instruments that I know I want and where those things generally are going to go, but I’m keeping it pretty open in that sense, too. There’s also going to be an orchestral element to this score, and I’ve written quite a bit of that now, but I’m still waiting for some of it, too. I know one or two of the main folk song melodies I want to use, but there might be other ones that I’ll discover when I’m there.”

Danna likes to be able to compose and record music into his Mac or Titanium laptop while watching digital video, even when on location, and his assistant, Andrew Lockington, has created an interesting setup that allows him that luxury. A Sony DVMC-DA2 box hooked up to the computer converts analog video into a digital signal (and vice versa). “It connects up to a computer via FireWire,” explains Lockington. “What I did was scanned in the movie and turned each reel into a DV file that is stored on an external FireWire drive.” Using Logic, Danna can then open up the DV file (a Quicktime file is also possible) and watch it while working inside Logic.

“The main advantage of that is we wanted them to be able to watch the movie on the laptop, all by itself, if they wanted to,” continues Lockington. “And if we had scanned it in at a higher compression rate, then as you make the Quicktime window bigger on your screen, the resolution would disappear. That’s part of the reason we had such a large file [5 to 6 gigabytes per 20-minute reel]. With DV, you don’t have a choice. It automatically scans it at a certain level, and if you’re viewing it at a smaller window level, it’s still the equivalent amount of information. It’s just using the CPU to break it down.”

Now, Danna can record digital audio right onto the internal hard drive of the Titanium, allowing him to improvise music while watching the video. “It’s very similar to if you were working with a video machine,” says Lockington, “but there are no sync problems, no delay in one thing synching to another, because it’s all inside the computer. So, once you set the sync point, then it will be in sync exactly the rest of the way. It works really well. We were a little bit surprised that it worked, actually.”

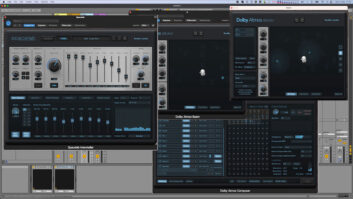

Danna’s basic writing studio in Toronto is equipped with a Mac G4 with Logic Audio 4.6.3, a Mackie D8B board and Genelec 1031A speakers. When asked whether he plays his samples on keyboards or chops them up, he says he has done both, but nowadays, Logic allows him to do it all. The composer owns many keyboards, but their individual importance varies from project to project. “Sometimes it’s pencil and paper, sometimes it’s mocking up,” Danna says. “Right now, I’m using the Roland XP-5080. I had a bunch of Roland samplers — the S750s and 760s — to mock up orchestral stuff, and now most of it fits onto the 5080. I still like the Roland library. I have GigaStudio, but I find I don’t use it very much because the Roland samples are the ones that I find are the best for mocking up.

“I think you can get better accuracy with other libraries, but I never synthesize acoustic instruments here,” Danna continues. “I synthesize them only for the purposes of a mock-up. Things always get re-recorded, so if I’m mocking up an orchestra, it’s only to be thrown away and replaced by a real one. If I didn’t have a budget to use an orchestra, then I would probably not go for that size of a group. I don’t want to try and spend my time synthesizing acoustic instruments. That’s why I like the Roland samples, because they give you a quick idea of what’s going on. They’re probably not incredibly accurate, but [they are] good enough.”

Danna owns numerous electronic sound sources, from a Virus to a D-50, and the main keyboard he uses for triggering is the Roland A90. The composer also owns vintage gear like Poly-6 synths and old Revox tape recorders. While Danna possesses a lot of processing gear, he notes that a lot of it remains unused today because of the proliferation of plug-ins. “But the things I still use quite a bit are the LXP-5 [and] Lexicon Prime Time,” states Danna. “I like the old, dirty stuff. I use a Quantec QRS almost exclusively. It’s my favorite reverb. It’s from the ’80s, but it just sounds amazing.”

Danna does not mix or master in his studio, nor does he have Pro Tools. “For Ararat, I’m recording bits in Armenia, bringing them back into the computer, and then I’m writing the orchestral part, which will then be recorded in London. We’ll be mixing in London, so I’ll be bringing over the finished folk music audio files, probably dropped into Pro Tools, because we’ll be recording the orchestra into Pro Tools.”

When it comes to recording and mixing his Canadian productions, Danna often works at the state-of-the-art CBC facilities in Toronto with Ron Searles. His other main engineer is Brad Haehnel, who is Los Angeles-based. He uses both of them for recording and mixing; which one depends upon where the project is. The composer has also used a few music editors over the years, including Tom Milano.

The one recent exception for mixing in his writing studio was Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding. “I did mix here because it was an extremely low-budget film, but it’s unusual that happens,” Danna remarks. “I don’t even have a center speaker here. When I did Monsoon Wedding, I had the Mackie D8B — in fact, that was the first project I used it on — and I rented a center speaker. The desk is made for surround mixes, so it was really fun. I did everything from start to finish on that, and I think it turned out really well.”

Although Danna has been at his studio space for 10 years, he has never named it because he does not think of it as a studio. “It’s just where I work,” he says. The composer lives in a high-rise condominium overlooking a lake. He lives in one unit and then has another for composing, complete with an office, an assistant’s room and the studio. “So it’s kind of home, but I get in the elevator,” he observes.

Did he face many challenges in converting a conventional apartment space into a studio? “None at all,” Danna replies. “There’s a huge living room, which had floor-to-ceiling windows that look out over the lake, which is why I’m still here, even though I’ve run out of space. The view is amazing, and it’s different every day. I look at the Toronto Islands, which are somewhat unspoiled [areas], so I look out at trees and water. That’s what you want to look at when you’re working. There’s glass all over the place, which any acoustician would wince at if he saw it, but I don’t care. The view is more important than the acoustics.” Because he only records keyboard parts here, that fact is not a sonic pitfall.

“As far as work, it’s just fantastic,” Danna beams of his studio. “I’ve got everything just the way I want it. Everything has nice wood. I’ve got good work lamps. I’ve got two 17-inch monitors for the Mac and another one for the Mackie. The workspace is really comfortable and very efficient. But as far as being in a condominium, I don’t record here, so I don’t need any acoustic treatment. And I don’t monitor loud at all.”

During the course of his lengthy career, Danna’s aural adventures have taken him around the globe, and modern technology has allowed him to venture to exotic locales independently. “We’re using a studio that’s in Armenia, but I’m bringing all my own stuff,” he reveals. “We’re basically using a Soviet-era studio space, which will sound great. I’ve worked in these Soviet-era studios before, and the space is amazing.” But the technology leaves a lot to be desired, hence the need for his Titanium setup and bringing his own mics.

“I’ll be able to be self-sufficient to a large extent, depending upon what I find when I get there,” Danna explains. “I end up doing that a lot. In Morocco, I ended up setting up in a big, empty hotel room [for 8MM], and I brought my own power and everything. That’s where I end up a lot, looking for these less-traveled paths as music sources.”

While this laborious process makes things more interesting, it also invariably makes more work for the composer. But he believes that the end results are worth the trouble. “When [the score] works, and it’s very well-considered and conceptualized, you can see something that really helps the understanding of the film and helps the theme of the film in a very elegant and thought-provoking way,” Danna concludes. “I’m really against the idea of throwing world instruments into a score just because they’re the flavor of the moment. You better have a very good reason for choosing your instruments. You need to think very carefully [about] what it is you’re trying to say and what instrument can best say it, what connotations all those instruments have.”

Traveling the world and absorbing new cultures in a quest for fresh sounds certainly spices up his scores. “I find that it’s the thing that gets me most excited,” Danna declares. “I love learning about new kinds of music, listening to nothing but Armenian music like I’ve been doing for the past two months now. And to me, that’s what the process of filmmaking is all about — just immersing yourself in a different world for a while. Hopefully, I’m able to transmit some of that in the music that I make.”

Bryan Reesman is a contributor to Mix.