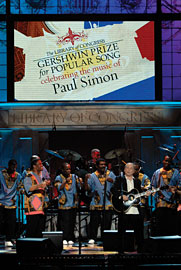

One of the highlights of the concert aired on PBS was Paul Simon’s performance with Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

This story I’m about to tell begs to be adapted as the screenplay for a buddy movie. The plotline goes back four decades to the leafy quadrangles of Princeton University, motors up the New Jersey Turnpike to Greenwich Village and then crisscrosses the country in a mobile truck with the King Biscuit Flower Hour crew before working up parallel subplots in New York and L.A. The climactic section, set in the present, is played out against a tableau of gleaming hardware and technological breakthroughs, which only serve to reinforce the deep and longstanding bond that connects the protagonists.

The main characters are Bob Kaminsky, once a producer for King Biscuit and now a partner at RipTide Music, a “business-to-business record label” in L.A.; XM Productions/Effanel Music head Randy Ezratty, whose remote trucks were once used by Kaminsky for King Biscuit remote recordings; veteran producer/engineer Robert Margouleff, founder of Hollywood’s Mi Casa Multimedia; and studio architect/acoustical designer John Storyk, co-owner of New York-based Walters-Storyk Design Group and the Princeton classmate of Kaminsky’s brother, Peter, and soon thereafter Kaminsky’s roommate in a Village bachelor pad, as well as his bandmate in a blues combo.

Storyk and Margouleff became friends when the latter was recording Stevie Wonder’s Music of My Mind album at Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios, which had been Storyk’s first major studio project. Margouleff is one of two godfathers of Storyk’s daughter, as is producer/engineer Eddie Kramer, who worked with Storyk on Electric Lady. He describes Kaminsky as an “unofficial godfather.”

Spider-Man couldn’t weave a web this tangled, but there’s more. It was Storyk who introduced Kaminsky to RipTide founder Rich Goldman a quarter-century ago, when Kaminsky was doing A&R for A&M Records and Goldman owned and ran the Storyk-designed Fifth Floor Recording in Cincinnati. A quarter-century later, Goldman and Kaminsky are working side-by-side at a company whose musical range, Kaminsky notes, “goes from indie bands to the Library of Congress.”

The joint mission that brought all of the above back together in 2007: creating and recording a concert and TV special for PBS commemorating Paul Simon being honored with the first Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song.

The production team at Mi Casa. Standing: Brant Biles (left) and Robert Margouleff; seated, Bob Kaminsky (left) with Mix’s L.A. editor Bud Scoppa.

The seeds for the event were sown in 1999 when the Kaminsky brothers approached Dr. James Billington — the Librarian of Congress and Kaminsky’s professor back at Princeton — with the concept for bestowing what would be the nation’s highest honor for songwriting. Fast-forward eight years to the moment when the Gershwin Prize finally became a reality, with Kaminsky as the executive producer and brother Peter functioning as head writer.

“When Paul said, ‘Yes,’” says Bob Kaminsky, “the first call I made was to Randy at Effanel to make sure we could bring in John Harris, who worked with me during the King Biscuit days, and Mitch Maketansky, a great audio producer who was trained at King Biscuit. We then confirmed XM/Effanel Studios in New York for the mix. And then I decided to do the post-conform, sweetening and correction at Mi Casa because TV shows are all over the place and these guys know how to make it into a cohesive audio experience.”

A week of rehearsals took place on a New York soundstage taped off to mimic the stage of Washington, D.C.’s Warner Theatre stage, with Effanel’s Digidesign ICON-equipped L7 truck parked outside. “We then moved the whole thing to George Washington University and rehearsed there for two days, and then moved the whole thing again to the Warner Theatre,” says Kaminsky. “So the band was playing together for 10 days. Paul was at just about all of the rehearsals. We had a fantastic afternoon watching him teach James Taylor ‘Still Crazy After All These Years.’ That was like seeing a master class in song interpretation.”

The concert, which took place on May 23, featured Art Garfunkel, Taylor, Stevie Wonder, Lyle Lovett, Allison Krauss, Stephen Marley, the Dixie Hummingbirds, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Yolanda Adams, Jerry Douglass, Marc Anthony, Jesse Dixon and Shawn Colvin. The three-hour show would be edited down to 90 minutes for the PBS special, which aired June 27.

The Pro Tools and RADAR files were transferred to Jazz At Lincoln Center for mixing on one of the facility’s three ICON controllers, with Harris — who, like Ezratty, had recorded countless King Biscuit concerts with Kaminsky by his side — and Rob Macomber at the console. Phil Ramone mixed Simon’s performances with the artist on hand.

Says Ezratty: “The L7 truck was designed as a clone of Jazz At Lincoln Center Studios, so everything that John worked on in preparation and during the show was instantaneously recalled. That made the project flow more efficiently than anything we’ve ever done.”

From there, the mixes were sent to Mi Casa for 5.1 post-production sweetening, with Margouleff’s partner, Brant Biles, at the Sony SIU 100 interface. Back in the ’90s, Margouleff and Biles had come up with the idea for a facility dedicated to creating state-of-the-art audio for TV viewing. They set up the facility in Margouleff’s Spanish-style home at the base of the Hollywood Hills; its original owner was Bela Lugosi.

“This show is the real convergence of everything that’s good about audio on television,” says Margouleff. “It brings together the best possible audio in 5.1 and the best possible reproduction with high-definition video — and it doesn’t get any better than that.”

It took a lot of work to make the sound of the concert as aired seem completely natural. Biles worked primarily with the SADiE PCM-H64 recorder/editor running CEDAR Retouch and the same company’s noise-reduction package. “We did the project in full surround,” Biles adds. “There was an editor in New York who did his stereo version and that served as a template, with down-and-dirty rough cuts. Two recordings were done at the show — a Pro Tools recording of the band itself and a 24-track RADAR recording with all the announcer, ambience and voice-over mics. So it was a matter of taking the realized video edit and putting these pieces together — being able to push audience and emphasize response to jokes and things like that. There were also clips to integrate. You can hide a lot of things in stereo, but when you’ve got a mix of musicians and then ambience mics placed in your mix throughout, it’s much harder to crossfade from one bit of audience to another and not hear the difference in audience attitude over the course of the show. So sometimes I would have to take their mix, sample-align it with the RADAR tracks and supplement the ins and outs of the songs.”

Says Kaminsky of the process: “Thanks to DigiDelivery, we were able to take mixes from a studio in New York and have it translate perfectly to a studio here in L.A. One day we called Effanel in New York, and said, ‘Hey guys, the piano in the Marc Anthony song needs to be a little bit louder and the guitar solo needs to be a little louder. Can you redo that and post it in two hours?’ And they went, ‘Yup.’”

In 1980, while doing A&R at Arista Records, Bud Scoppa tapped Margouleff to produce the Bus Boys’ album Minimum Wage Rock & Roll. In another twist of fate, Scoppa wrote the liner notes for Columbia/Legacy’s reissues of Simon & Garfunkel’s studio albums; he recently completed the notes for Simon & Garfunkel Live 1969.