TIPS ON PURCHASING AND USING YOUR FIRST SET OF IN-EAR MONITORS

In-ear monitors are now widely accepted as an alternative to wedge or side-fill monitors for live performance. First developed in the early ’80s at the prompting of such innovative artists as Todd Rundgren and Stevie Wonder, the technology has now matured to the point that large equipment manufacturers have entered the market with lower-cost products, making “in-ears,” or IEMs, affordable for a broad range of performing musicians. (It should be noted that the brand name Ear Monitors[R] is a registered trademark of Future Sonics.)

The major benefits of IEMs are several: When operated correctly, they can help conserve the hearing of both the artists and the monitor engineer; singers who risk straining their voices when booked for three or four gigs in a row now find that they can perform comfortably for five nights a week, a key factor in making high-overhead tours profitable; and entertainers with impaired hearing, who can find live shows especially challenging, can use IEMs to extend their performing careers by years, even decades.

For bands just starting out, IEMs can completely replace a rehearsal space sound system. Better yet, because an IEM system creates its own acoustic space between the ears, even the most claustrophobic practice space can be made quite tolerable. For the same price as decent amps, wedges and equalizers, an IEM system can serve a three- or even a four-piece band quite well. The same rig can be used in the studio and can also simplify club gigs and support slots, ensuring a level of consistency that is otherwise hard to achieve with a different wedge system at every show.

On the other hand, in-ear monitors are perhaps the most frustrating products to shop for. Unlike almost every other piece of equipment onstage or in the FOH and monitor sound systems, IEMs cannot be easily auditioned or A/B’d with comparable equipment, and when you’re talking custom models, only one person can listen to the product at a time.

Setting up to use IEMs requires considerable preparation and forethought. Band members and management need to be convinced that the serious cash outlay will be well spent, and monitor engineers need to be sure that the budget will cover all of the specialized equipment necessary to provide each band member with a quality ear mix. And don’t forget to include a small tackle box for keeping the ear-molds and belt-packs together, along with a supply of batteries and cleaning supplies for the molds. Misplacing an ear or pack can result not only in a serious financial setback, but can also be a real show stopper.

CHOOSING YOUR MOLDS

There are essentially two types of ear-molds: generic and custom. A variety of manufacturers now offer the generic, one-piece-fits-all models, and some can be upgraded to a custom fit with “tips” or “sleeves” from the makers of custom molds, which are made from an impression taken of the user’s ears. One difficulty for those purchasing custom molds is that they cannot hear their molds before they buy them. The tendency is for first-time users to try someone else’s generic piece. While that is an inexpensive way to check out the actual ear-piece driver, it may not be the best solution, but a much worse idea is to audition an IEM system through a $20 pair of Walkman ear-buds. Because properly fitted IEMs, whether generic or custom, will tend to block out ambient sounds on a performance stage, the system will allow for accurate monitoring at much lower volumes than wedge systems. Walkman-type ear-buds block out very little stage noise, so musicians typically turn them up really loud to overcome drums, guitar amps and P.A. backwash. At these levels, cheap ear-buds usually distort, and excessive levels, distorted or otherwise, will ultimately damage the user’s hearing.

Yes, the difference in price between the least, expensive generic models (a couple of hundred bucks) and the best custom molds (about $700) is considerable. But many musicians have spent more than that on a poorly chosen guitar, digital effect or other toy of the moment. For a product that can both improve live performance and help preserve hearing – and will be more comfortable – the extra money is well spent.

Having said that, it is worth noting that good sound is a matter of taste. Everyone’s ears are different, and variation in the size and shape of the ear canal will affect how any given transducer couples to the eardrum, with the result that the same product will sound a little different to each user. Also, each of us has had varying amounts of hearing recruitment (a less controversial word for hearing damage). Over the years, many musicians and engineers have developed a notch at around three kHz, while others are missing entire octaves of high frequencies. And everyone listens to music differently – most musicians are understandably focused on their own instruments, while engineers must keep an ear on the big picture. And though many in-ear monitors are endorsed or promoted by the rock stars that use them, the specs are often fuzzy and nigh impossible to check.

Beyond the choice of generic or custom molds, there are also two different types of transducer components used inside them. Balanced-armature systems (or “ribbon drivers,” as they’re incorrectly called) offer extended high-frequency response, helpful for older ears that may benefit from a little extra sparkle. Dynamic drivers, which are usually ported to tune the low end, have a response that typically falls off above five kHz. This roll-off can be corrected with a high-frequency boost in the mix or the belt-pack, though some say the unequalized lack of highs prevents hearing fatigue. Most recently, several manufacturers have begun offering two-way designs that combine a pair of balanced-armature drivers with a crossover. These units offer a fairly flat, full-range response.

How do they sound? To my ears, the two-way, balanced-armature molds can sound like a pair of Sony V6 headphones, while those with dynamic drivers sound more like Sony 848 ear buds. But don’t take my word for it. Because individual hearing and tastes vary, I recommend that new users carefully compare the listening experience each transducer type offers. Most of the newer designs are available in generic versions, so, having decided which type has the most pleasing sound, users can decide whether to settle for a generic piece and save a few bucks, or to get the isolation and comfort advantage of a custom mold designed to fit the ear. For about $100, several of the generic models can be upgraded with custom molded tips to give a more comfortable fit.

I have tried dozens of different models and now have several favorites, depending on the kind of music. Yet there are some models I don’t like that others seem to favor. It’s worth repeating that, when it comes to choosing the right model for you, it doesn’t matter what I prefer or what Madonna uses.

It’s also worth remembering that the frequency response of the tiny transducers in-ear monitors is lacking below 100 Hz. Though most concert sound systems throw the low end from the subwoofers back onto the stage, some performers – especially drummers and bass players – won’t be pleased unless their ear monitors are supplemented with LF, which requires yet another output from the desk. Purpose-designed products, known generically as “thumpers” or “shakers,” can be mounted to a drum throne or a riser to provide the lowest octave of response through bone conduction. A crude but effective alternative is to take an unused monitor, turn off the horn and drop the crossover to 200 Hz. In close proximity, such will provide enough supplemental low end to help out. (For more information on contact transducers, see the sidebar “Give Your Ears a Rest.)

LEARNING TO MIX IEMS

Mixing in-ear monitors is not much harder than dialing up a good headphone mix. The first step is to get used to them, and you can start using IEMs immediately, whether or not the band uses them. I stopped using a cue wedge at my console years ago, and I always monitor on “ears” during the show, even if the band is all using wedges. Apart from anything else, it’s easier to shoo hangers-on away from the monitor mix position when there is no cue wedge to listen to. Plus, using a wireless cue system and the same kind of ear-bud as the performer gives me a high degree of confidence that I am hearing what the performers are hearing.

The ability to put together an ear mix quickly is a great asset, and monitor engineers new to mixing “ears” might consider getting some practice by creating dummy headphone mixes during idle moments while mixing traditional speaker-based monitors. After all, after the first three songs in a set there is often little for a “wedge” engineer to do. And because the difference between a precise and isolated in-ear mix and the typical ambient stage wash from multiple wedges is quite significant, it pays to be prepared.

When you do finally start a band on IEMs, present them with a mix that’s already built, especially if it’s their first time on IEMs. The experience of putting in ear-molds and finding nothing in the mix is disconcerting, even for experienced users; make a habit of preparing and checking each mix before it is handed out. Obviously, it is desirable to have a single style for the monitor engineer and the entire band so the engineer can reference each mix. Different group members will probably have varying needs and tastes, but a mix can be modified easily to an individual’s taste simply by inserting an EQ across his or her output.

Mixing style can vary greatly between in-ear and traditional wedge-based monitors. Performers who rely on speakers are used to hearing both the stage acoustics and the sound of the P.A. coming back from the room. Players whose instruments are nearby are easily heard, but instruments on the other side of the stage will need to be in the wedge. Levels are all nominally about the same, but to hear an input in a wedge mix, it has to be at a higher level than the stage wash; most inputs in a wedge mix will be set at above 11 o’clock.

The in-ear mix, on the other hand, must contain everything the performer needs to hear, and small level changes are easily heard. Some inputs will be plenty loud at 9 o’clock, while others (usually the “me” inputs) may be wound nearly all the way open. Levels for in-ear mixes must be set much more carefully than for wedges, so the “velvet touch” will be appreciated. “Split the difference” is a frequently heard instruction for IEM engineers adjusting levels.

Depending on the band’s arrangements and playing style, levels of some inputs may need to change from song to song, and for in-ear mixers this may require more work than is typical when wedge mixing. Inserting compressors in some channels may help, but it may be more effective to simply mix the show, as one would at FOH. The hardest decisions will be which sends are going to be pre-fader and which will be post. Anyone still on wedges will be better off pre-fader, because they’ll require fewer inputs and level changes, and it’s best to make each IEM performer’s “me” inputs pre as well.

A frequent problem with singers using IEMs is that they quickly learn that they can back off the mic and then ask for more level, a trick they can’t get away with on wedges. The result is more stage wash into the vocal mic, which makes the FOH engineer’s job harder and rarely improves the monitor mix. My solution is to open each singer’s input up all the way and then offer to turn other inputs down in the mix. Plus, you can surreptitiously turn a singer’s vocal down in his or her own mix, which usually gets him or her to hug the mic during quiet songs when he or she might otherwise back off.

Stereo mixes are vastly superior to mono for in-ear monitoring. It is much easier to identify the various components in a mix when they are panned across a stereo sound field, and stereo can help keep monitor levels lower, which will reduce ear fatigue and conserve hearing. Check this for yourself by switching a headphone mix back and forth from stereo to mono.

As mentioned above, it is easy to make an in-ear mix sound better by inserting a stereo graphic EQ. The response of the actual IEM driver may not be perfect, and most musicians will have some differences in the response of their ears, but minor EQ tweaks can quickly improve the perceived sound without having to change anything else. In fact, boosting highs to compensate for high-end roll-off in either an ear-mold or a wireless will provide a Dolby-like mechanism to cover up some of the noise in a wireless system. Wireless users can even walk over and tweak their own mix. After using mix EQ for a while with ear monitors, you may learn quite a bit about the combination of your hearing and the IEM products you’ve chosen.

SIGNAL CHAIN REVEALED

There are no shortcuts to quality. Though technology has improved over the past decade, the more expensive products tend to perform better. Once you put transducers right into your ears, the quality of all the components in a monitor system becomes more easily apparent. The mic preamps in most live consoles are satisfactory when heard through speakers, but the differences between desks are easily heard when listened to in the isolation offered by good in-ear systems. These differences are especially noticeable with vocals. The use of outboard studio-quality mic pre’s for the money channels can provide a better listening experience.

Similarly, the qualities of digital reverbs are more easily heard on in-ear monitors. Most performers will enjoy hearing a little reverb on their voice or instrument, but sharing reverbs can be cumbersome and confusing, and simply inserting a reverb in the overall mix is not sufficient. Dedicated quality reverbs allow the operator to give each performer exactly the mix he or she wants.

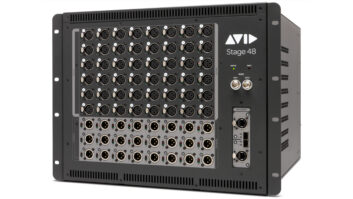

Though they eat up more inputs, reverbs definitely sound better in stereo. However, once you provide a stereo mix plus a reverb send for every musician using IEMs, the number of desk outputs required for in-ears nearly triples over that required for a wedge-based monitor system. A band with five musicians and three background singers might require as many as 24 output buses if they are all on in-ear mixes. Fortunately, there are strategies to reduce the number of mix buses. Reverbs dedicated to a single input can be fed an input from the channel direct output, and extra reverb send buses can be created by using an outboard line mixer to combine direct outputs from several channels.

Returning reverbs in stereo will either take up a stereo input (all too rare on monitor desks) or two mono inputs. Fortunately, many monitor consoles offer auxiliary inputs, typically used for line level signals like CD players, but equally useful for bringing in the outputs of a sidecar desk. Because these extra aux ins usually have dedicated volume controls and can be monitored on the cue bus, they can also be used for reverb returns. Multi-effects units often have enough onboard parameters to provide substantial EQ control, so a lack of board EQ on the aux ins may not matter.

Another way to reduce the number of monitor desk inputs needed, while also freeing the monitor engineer from operational overhead, is with additional small mixers onstage. Many keyboard players already use mixers in their rigs to give them independence from the monitor system and can happily program or noodle on headphones while the rest of the crew goes about getting ready for soundcheck. By sending band and vocal submixes to the keyboard mixer, you can probably give the mixer everything needed for an IEM mix; conversely, using the keyboard mixer’s output instead of individual DIs on each instrument can free up quite a few input channels on the monitor desk. In most situations, background singers can be quite adequately served with a small mixer fed with splits of the vocal channels and an instrumental submix from the monitor board; a dedicated reverb may also be necessary.

COMMUNICATIONS

Clear communication between the operator and performers is a cornerstone of mixing monitors, and IEMs lend themselves to concise and private two-way discussions during the show. Clear-Com’s TW-40 walkie-talkie interface allows radio traffic to be injected into the party-line intercom system. For my cue mix, I use a wireless in-ear system set to mono. One input is fed from the desk’s headphone output, and the other has the intercom plugged into it. I can hear everything at once at a comfortable volume and in private, and the backline techs on the opposite side of the stage can communicate the requests of the musicians they work for without making a trip across the stage. Another simple way to facilitate communications is to place a spare microphone onstage so the musicians can talk to the monitor engineer between, or even during songs.

PROTECTION LIMITING

The use of “brickwall” limiters has been touted as a safety measure for hearing conservation, protecting the performer’s ears from inadvertent transients. Set correctly, brickwall limiters will kick in before the IEM system’s onboard limiters and, hopefully, before the onset of distortion. But the best safeguard is a vigilant, attentive operator who carefully provides a safe mix, and that is only one part of the equation. Because each performer has an individual master volume control on the IEM belt-pack, it is all too easy to turn up the mix to overcome stage volume or hearing deficiencies. However safe and stable the IEM engineer’s mix, the higher sensitivity and lower impedances of today’s ear-molds allows them to put out more than enough SPL to gradually cause hearing damage over time.

Perhaps the most important and overlooked feature of professional-quality ear-molds is the amount of isolation that they can provide. Even with brickwall limiters and good mixes, poor isolation will tempt performers to raise the volume. Long exposure to even moderate levels can damage hearing over time, so it is important that performers are aware of their volume control positions. A musician who learns to first try something other than simply “turning up” will go a long way toward preserving his or her hearing.

TACTILE MONITORS ENHANCE THE IEM EXPERIENCE

In-ear monitors have brought big changes to the live stage environment, and most FOH and monitor mixers familiar with IEMs comment on how much cleaner their mixes can be with instrument amplifiers isolated offstage and wedge monitors absent. However, many musicians, especially bass players and drummers, find that IEMs fail to deliver the visceral ooomph that they are used to from their own bass rigs and drum monitors.

Fortunately, our perception of sound is not just dependent on our ears. Sound or vibration can be felt with the body – we are all familiar with the sensation of a refrigerator’s vibrations being sensed through our feet on the kitchen floor. In fact, our skeletal structures transmit full-spectrum sound instantly, without the need for air-transmitted sound, and this “tactile sound” bandwidth ranges from a subsonic 20 Hz up to 800 Hz for most individuals. In fact, studies have shown that most individuals are very sensitive to tactile sound and can detect a shift of as little of 1.8 Hz, a sensitivity that approaches the acuity of the human ear.

Though primarily developed for amusement parks and the military, which use them to transfer vibrational information directly into seating and floor structures, tactile sound transducers have obvious applications in stage monitoring. A single tactile sound transducer can effectively replace the LF speaker cabinets that bassists and drummers typically use to supplement their IEM systems. This method of audio information transfer has many advantages over air transmission, including greatly reduced LF leakage into open mics on stage, reduced room resonance and fewer standing waves caused by onstage subwoofers, and zero interference with other speakers, which is a major source of distortion in multispeaker sound systems. There is an economical argument, too: Because the ear is relatively inefficient at lower frequencies, it takes a lot more energy to move air with a traditional drum monitor setup than it does to produce the physical sensation of bass frequencies through a tactile sound transducer drum throne mount. Further, a tactile sound transducer is less likely to induce the hearing loss inevitably associated with exposure to loud noise.

The drum throne “shaker” has been with us for a few years, but tactile sound transducers can also be built into a performer’s section of the stage or attached to a riser, creating a localized area with exactly the right amount of apparent bass energy. And because tactile sound transducers are sometimes used in swimming pools and hot tubs, watertight and weather-resistant models are readily available. More specific product information, plus a list of current users, can be found at www.clarksynthesis.com.