Listening to Bruce Springsteen’s song “The River” always makes me cry. I used to think it was just me. Raised East Coast and blue collar, I always saw in Springsteen’s ballad of failed dreams my family and the people I grew up with. Writing this story, I discovered that I wasn’t alone. As it turns out, tears are a pretty universal response to “The River”; you don’t have to be East Coast or blue collar to understand that our lives often don’t turn out as we’d hoped.

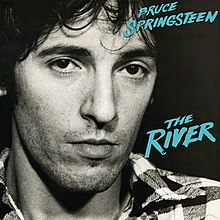

Introduced on September 22, 1979, at the No Nukes concert at Madison Square Garden, “The River” was never a single. But, a year later, it became the title track of a double album, Springsteen’s fifth. Set chronologically between the brooding, working-class vignettes of Darkness on the Edge of Town and the starkly hopelessNebraska, The River contains such patented Springsteen party songs as “Hungry Heart” and “Sherry Darling.” But running through it is an underlying theme of disillusionment that’s encapsulated perfectly in the song “The River.” A mid-tempo ballad, it tells the story of a pair of working-class teens forced by pregnancy into an early marriage and dead-end jobs. It also showcases the E Street Band at their best. Somehow solid and airy at the same time, the ensemble is masterful in its support of Springsteen’s lyrics and folk-style melody, juxtaposing musically plaintive verses against falsely hopeful choruses.

Recorded in New York City at the Power Station (now Avatar Studios) during a 16-month period, The River sessions were Grammy-winning producer/engineer Neil Dorfsman’s first real engineering gig. He recalls it vividly: “I was a huge fan of Bruce’s from early on,” he remembers. “When I heard they were coming in, I went to the studio manager and, basically, begged to be on the date. Bob Clearmountain started the project, did a track or two, then had to leave for a prior commitment, and they gave me a shot. I was so nervous the night he walked in, I was shaking. I was sure the first night would be my last. Little did I know it would go on for something like 16 months.”

In 1980, Power Station’s Studio A was becoming legendary as the place to get a big, live sound. However, at that time, studio lockouts weren’t the norm; the sessions that became The River were cut entirely on the night shift. Dorfsman and his assistants tore down each morning and set up again each evening — six or seven nights a week. “It was recorded live, so it was the same setup every night,” he says. “My assistants re-set up the room, and I got to the point where I could walk in the control room, set up the entire console, my patches, four different headphone mixes, all my levels and be ready to roll in 20 minutes.

“It was fun. But tearing down the studios every night was brutal. I’d get to the studio at 5 p.m. and wait for the previous session to end, usually at 6:30. Then we’d go in and hit it. In an hour we’d be done and the band could walk in and start playing. In fact, they’d often start playing as things were still being plugged in. If it sounded okay, we’d get it on tape and go. That was Bruce’s sound: immediate and alive.”

The setup was a big one, with Bruce and all six members of the E Street Band. Max Weinberg’s drums were in the main room, where a vocal booth was also constructed for Springsteen out of goboes, plywood and blankets. Organist Danny Federici with his B3 and baffled-off Leslie, and pianist Roy Bittan were set up in their own iso room, along with miscellaneous keyboards. A second, deader iso room housed the amps: Springsteen’s Fender Bassman, guitarist “Miami” Steve Van Zandt’s amps and Garry Tallent’s baffled bass amp. Saxophonist Clarence “Big Man” Clemons had his own booth on the side of the control room.

Studio A’s control room housed a 32-channel Neve 8068 console that was, according to Dorfsman, “totally maxed out.” He recalls using either a Neumann 87 or a U67 on Springsteen’s vocal, with either a Teletronix LA-2A or a UREI LA-3A limiter and Pultec EQ. “The Power Station didn’t have a lot of vintage mics,” he says, “and we kept the setup simple in case he wanted to come back later and change something, which, actually, he never did.”

The rest of the mics were simple also: two Shure SM 57s for each guitar amp, “one straight and one at an angle on the center of the cones and a Neumann U87 and a couple of Sennheiser 451s” on acoustic guitar. The B3’s Leslie was recorded in stereo: two 57s on top, spread left and right, and a Neumann 47 FET on the bottom, mixed up the middle with the stereo tracks “probably compressed with two Neve compressors linked to keep it sort of burbling instead of pokey.” Bass was taken both direct and with either a Sennheiser 421 or a Neumann 47 FET on the amp. Both DI and mic bass channels were run through the console’s pair of 33609 limiters with no EQ.

The piano, miked with two Sennheiser 451s or 452s, wasn’t compressed, but it was generally “severely” EQ’d through Pultecs for a very bright sound. “Power Station had 24 Pultecs in the control room,” explains Dorfsman. “That was a lot of the sound of that record. Everything pretty much ran through them whether they had EQ or not. There was a patch between the console and the tape machine, and Ed Evans, the chief tech, had done a mod so you could go through the tubes of the Pultecs without going through the EQ stage.”

The drum mics were classic Power Station: an SM57 on snare, a Sennheiser 421 and an RE20 on the kick drum, which was housed in a tunnel made out of a packing blanket. On the toms — top and bottom — 421s. For hi-hat, a Sennheiser 451 with a 20dB pad; for the overheads, 451s with 10dB pads. Room mics were two U87s, “up pretty high, sometimes facing away from the drums toward the wall for more reflection and longer delay, or, depending on the tune, sometimes low to the ground and facing the drums, about 20 feet away. It was fairly well squashed with a pair of LA-3As — nothing crazy — just to give them some punch. There was a moderate amount of console EQ used, but no real outboard EQ. The sound was the room, the board and the band. The hallmark sound for recording this record was the ambience and the brightness. When you were monitoring in the control room, you could almost never have too much ambience; Max loved it.”

Dorfsman recalls cutting several versions of “The River,” trying out different tempos and a more embellished rock ‘n’ roll arrangement. “I don’t, in general, remember the specifics of each song,” he admits. “We were doing multiple takes of every song 20, 30, sometimes 40 times, so things really blended together. Bruce cut something like 50 songs, with multiple — at least 15 — takes of each tune. We had over 400 reels of tape. But I do remember, when we first heard “The River,” I looked at my assistant and went, ‘Wow, this is great.’ It had a special vibe and everybody — at least everybody at my end, in the control room — knew it was a special tune when we cut it.”

The album’s final mixes (except “Hungry Heart,” which was mixed by Bob Clearmountain at Power Station) were done by Toby Scott. Although Scott has worked in various capacities with Springsteen for over 20 years now, “The River” was also his first Springsteen project. In 1980, he was manager and chief engineer of producer Chuck Plotkin’s Clover Recording in Hollywood.

“Chuck helped out on the mixes for Darkness at the Edge of Town,” Scott explains, “and they [Springsteen and manager Jon Landau] called him in again when they had trouble getting the mixes for The River. They’d had Bob Clearmountain mix about a dozen songs on two different occasions, and they’d done mixes with Neil Dorfsman. When they ended up calling Chuck, he got me into the picture because we worked together. He said something like, ‘Toby’s my right-hand man. Let him mix it, and I’ll just refine his mixes.’

“So they gave me a song. I worked on it for two or three hours, then Bruce listened and said, ‘No, that’s not it. Where are the room mics? I want it to sound more like this!’ He shoved the room mics way up on the faders so the drums sounded like they were in a basketball court! Obviously, that was going to be integral to the sound of the band. They left, I rebalanced, and when they came back in, they said, ‘Sounds good, let’s try another song.’ I mixed a few more, things were going well, and then they said, ‘Okay, now let’s really mix the songs.’ Because Bruce, at that time, was into very meticulous control of everything. He took as long as was necessary.”

A lot of what Scott spent time on was getting the room sounds and reverbs right. “I had to figure out a way to control the room mics,” he explains. “They had a lot of cymbals in them so that when you turned them up loud, they washed out the drums. It ended up that I used a couple of Eventide 910 Harmonizers to create a multi tapped delay, which I popped the drums into, and then sent out into our studio through [Altec] 604E speakers, recorded into a couple of 87s. Our studio wasn’t very live, so I nailed plywood boards on the walls.”

Wanting the mixes to be “great,” as Scott says, he and Plotkin auditioned a prototype Sony 1610 digital recorder and settled on it as their mix format. Working on Clover’s 32-channel, 8-bus API console, and taking approximately two days to get what Scott calls the “sound picture” for each song, they laid down mixes and variations of mixes. “There wasn’t any automation,” Scott points out, “so the mixes were really a performance. We did hundreds of variations: with backgrounds and without; lead up, lead down; more echo; more slap. Once we started taking mixes, I think we averaged 75 variations per song.”

For “The River,” room sounds were integral, but the added reverbs were also striking, especially noticeable on the first entrance of harmonica and vocal. As Scott recalls, they comprised an EMT 250 digital reverb and Clover’s two EMT 140 plates, which he had damped and made less “metallic-sounding” by gaffer-taping the sides. Those plates also had a unique trait: Set in a separate room against a cinder-block wall, they would heat up during the day and give off a softer, more mellow sound. At night, the plates were tighter and brighter. “You’d bear this in mind,” Scott says. “Most of Bruce’s mixes were laid down in the middle of the night.”

For Roy Bittan’s piano, which leads much of the track, Scott used two Eventide 910s, “one spread so that the harmonized, delayed side was on the left, and the undelayed sound was on the right, and the other set at the reverse, so that the delays and harmonizing weren’t the same.”

Scott’s favorite vocal limiter on the sessions was an EMT 156, which, even at that time, was a rarity. “Virtually no engineers knew how to work it,” he admits. “It was unity gain in and out, so it was all based on gain structure. When we first started, Bruce said, ‘I don’t like my vocal compressed; don’t do it,’ but I stuck it through the EMT and it worked incredibly well. He never noticed it. If the level you were sending in was right, and you followed the chart on the front panel, it carefully compressed to where it was seamless.”

Scott’s format for mixing was — and still is — to get the rhythm section going first, then to put up the vocal and begin working the chordal instruments around it. When he opened up Springsteen’s vocal on “The River,” he was surprised at his reaction. “I listened to the track a couple of times,” he says, “then I put up the lyrics, and it really got to me, the story of this kid who got a girl pregnant and trapped them both into a miserable life. I was sitting there, actually sobbing away at the console. And I was thinking, ‘Geez, how am I going to do this?’ Finally, it was, ‘I’ve got to get on with the job at hand,’ and I went on and mixed it. But even then, a couple of days later when I would listen back, I’d be sobbing again…it really was the most emotional song.”

I was lucky enough to catch Springsteen live twice before he turned superstar. It’s not that his performances changed; he’s still an incredible communicator, one of the few who can hold riveted a packed stadium. It’s just that those huge stadiums sometimes seem to be filled with Top 40 fans and clueless yuppies shouting out “Dancing in the Dark”! But, on the night in 1980 when I saw him perform “The River,” the crowd was still full of believers, and the shows were still gut-wrenching, emotional and intimate. As Springsteen and “Miami” Steve sang the last wordless notes to “The River,” as it slowly faded out and the stage went black, there was only hushed silence, the crowd too stunned to react. Driven to tears, if you ask me.