The old saw that “routine is the enemy of art” seems to be at odds with modern recording technology. Musicians work hard to find the right balance of predictability and surprise, yet the tools we use to capture inspiration require a high level of inflexibility. While those of us who work both sides of the studio glass try to balance the logical with the creative, it can be challenging to keep the tools from determining the finished product rather than the other way around.

advertisement

We set things up to work a certain way and, without realizing it, we’ve boxed ourselves in, creatively speaking. Typically, what comes easy is what gets done.

Of course, routines simplify our workflow. They remove barriers to productivity in order to allow things to go smoothly. For example, we use session templates in a DAW so that we don’t have to reconfigure our recording setup from scratch each time we want to work. Ostensibly, that leaves us with more creative time.

But sometimes barriers produce richer results. If I may appeal to the cynical readers of this magazine: Doesn’t it seem like better music was produced when it was more difficult to make records? Didn’t limited track counts, expensive studio time and the necessity to hone one’s craft onstage before hitting the Record button add up to a higher level of artistic achievement? You had to be committed on every level.

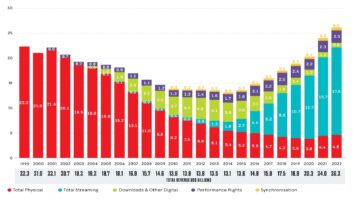

Now we have an unlimited track count in a non-destructive recording environment that we have 24 /7 access to. Everything we need is close at hand and available at an affordable cost. Theoretically that should allow us to write a song at breakfast, record it at lunch and upload it by dinner (to paraphrase John Lennon about creating the song “Instant Karma”).

Instead, we fuss over minutiae and remain non-committal about nearly everything. Why shouldn’t we? The technology allows us to wait until the very last moment before choosing the amplifier sound we want or the exact reverb setting for a string pad. We can see when the waveforms of the rhythm instruments are not perfectly aligned, so we fix them—because we can. And it’s good to know that we can easily replace every drum sound should the need arise. It’s both a blessing and a curse that we can view the edges of our work so clearly.

Therein lies the rub: We work toward perfection by practicing and running routines in order to increase our productivity, yet we need the ability to dash our expectations at a moment’s notice in order to create something fresh.

I can’t count the number of times that I’ve been in sessions where mics have been carefully placed on every part of the drum set, only to have them jettisoned during the mix in favor of a single omni sitting far off in the corner. Typically, the engineer wants things to sound as realistic as possible, while the artist is concerned with his or her vision of the song. That’s easy to work out when the jobs of artist and technician are divided between two people. But what if you’re wearing both hats?

Many of us like to think that lateral thinking comes naturally when we need it. We are, after all, in an artistic field. Books such as The Six Hats or The Art of Innovation are written for people who are unaccustomed to the creative process and out-of-the-box thinking. Or so we like to believe.

We expect that the years of work perfecting our craft will be the thing that saves us in tough situations. Often, it’s our ability to do the “wrong” thing that gets us over hurdles.

During one of the tracking sessions for the Tom Waits release Bad As Me, the rhythm section was trying to find its way through an arrangement, and one of the guitar parts just wasn’t working. It needed to be simple and naïve, but the guitarist just couldn’t capture the right feel. It wasn’t a matter of talent; this was a studio veteran who could, usually, play anything you asked for. Finally, after changing instruments and stripping down the part to no avail, Waits suggested he play the guitar upside down, as if he was a lefty. As the guitarist tried to navigate the fretboard with the hand that was normally used for picking, he nailed his part on the first take. Most importantly, he didn’t just try it. He went after this unusual request with full conviction and made it work. Ultimately, it didn’t matter who made the suggestion because the goal was to find the right part. The guitarist could’ve tried it himself without saying so, but the pressure of the situation had the surprising effect of corralling his lateral thinking.

We’ve all had that dream where we show up for an important gig and we’re either naked or have forgotten our instrument—some variation on this theme. Now imagine that it’s no dream. Rather, you’re working for the client of your dreams but you have become creatively naked. Would you sort it out in a tried-and-true fashion, or would you attempt something absurd? Would you do so with full commitment? How much would you be willing to risk?