Everyone from KISS to Green Day to 50 Cent has had a song or two on a videogame soundtrack. Gamers can hear their favorite bands while virtually racing cars or fighting space aliens, as well as listen to old and new game music, themes and effects on videogame radio stations and even catch composer interviews on the G4 cable network.

If gamers want to venture outside, they can hear music from Halo, Zelda and Mario, among others, performed live by U.S. symphonies, courtesy of large-scale multimedia productions such as Video Games Live, which is touring North America this fall. Stand-alone soundtrack CDs accompany most new games — some shipping with the game itself, others selling in retail outlets online and off.

Watch out for Cannibal Mother, a nasty creature from Jade Empire.

With $7.3 billion in revenue (U.S. computer and videogame software sales in 2004, according to the Entertainment Software Association), the videogame industry is catching up with film box-office receipts and is reportedly the only entertainment sector that has shown growth during the past decade.

With technological improvements such as more memory-rich DVD releases, incorporating surround sound, THX licenses, higher bit rates and 44.1k playback, audio designers have more freedom than ever to create captivating musical “foregrounds” that hold their own against high-action battle and sports scenes and corrupt virtual universes.

The path that music takes from pre-production to final mix closely resembles a film soundtrack’s creation, right down to its balance when played against dialog, Foley, field recording, sound design and original and/or licensed music. To illustrate the process, we asked composer Jack Wall and members of the Edmonton, Alberta — based BioWare Corp. audio team to walk us through the Xbox™ game Jade Empire™, published by Microsoft Game Studios. In contrast to this big-budget production, we picked apart PlayStation title Rise of the Kasai, an all-MIDI game with music composed by Rod Abernethy, Jack Wall, Keith Leary, Mikael Sandgren and Mike Reagan; Chuck Doud, music director for Sony Computer Entertainment America, served as audio director.

PRE-PRODUCTION

Set in mythological China, the single-person roleplayer Jade Empire blends ancient martial arts and mythical culture with gigantic serpents, mechanical insects and sweeping scenery. A highly complex production, Jade Empire contains 15,800 lines of recorded dialog and 6,900 vocal combat sounds from more than 400 speaking characters, not to mention layers of original sound effects and more than 90 minutes of score.

Rau goes after a dragon in Rise of the Kasai

“Initially, Dave Chan, our former audio producer, wrote up an Audio Vision document that detailed the audio experience for Jade Empire,” says Steve Sim, BioWare’s senior sound designer/audio technician. “We wanted the game to have an authentic Asian atmosphere and a very organic sound to complement the rich, lush visual environment, but to also have ‘Kung Fu movie-isms’ for critical elements in the game like combat.” The game’s producer and design crew met with the audio team to determine the sound design and music’s direction. BioWare then presented their chosen composer, Wall, with inspirational reference pieces, concept art and story synopsis.

Rise of the Kasai, the action-packed sequel to the 2002 Sony PlayStation game The Mark of Kri, also features warriors and an Asian-themed score, but with greater emphasis on intense combat. The game features an all-MIDI-driven soundtrack rather than streamed .WAV or MP3 files. In this case, pre-production involved recording drum samples, chants and Tibetan monks, which were then given to the composers. Audio director Doud oversaw the recording process of these elements, which took place in San Francisco, San Diego and L.A. studios. “We really went overboard with the amount of effort we put into this soundtrack,” he says. “We even hired a guy who builds his own custom instruments. He came in for a day and we made sample banks of those instruments and then shared those with the composers so they could incorporate them into their palette of sounds.”

COMPELLING COMPOSITION

BioWare brought Wall in early during Jade Empire‘s development, which, in his opinion, led to a better score. He first traveled to BioWare’s headquarters, where they “divulged the secrets of the game. At the time,” he says, “they had a prototype level they were getting ready to show at E3 2004.” BioWare had been working on the game since early 2003.

Wall’s score combines Western orchestral music with Asian instruments and percussion, but had to be palatable to Western ears. “I would write based on the fact that I needed music for various areas and various characters of the game,” he explains. Zhiming Han, who is fluent in Chinese and English music and languages, consulted with Wall on incorporating Chinese instruments into the score, then contracted the musicians, converted Wall’s parts into Chinese notation and translated Wall’s ideas and direction to the Chinese-speaking players.

The BioWare team, from left: Steve Sim, senior sound designer/audio technician; Shauna Perry, director of audio; Michael Kent, sound designer/audio technician; and Michael Peters, sound designer

“I’d give [Han] a piece of music, and say, ‘I think we ought to record this with a bawu, dizi or the 23-string guzheng,” says Wall. “We also used erhu and janghu, sort of the Chinese violin and viola, and Zhiming is a master of the yangqin, which is a Chinese hammered dulcimer. He was essential to this project.”

Wall used Private Island Tracks in Hollywood and Martinsound in Alhambra, Calif., to record percussion, which included a set of Taiko drums, a 42-inch-wide Hira Odaiko and a set of Shimi Daikos, among other pieces. Engineer Sam Lewis handled the Private Island sessions, recording through a Trident board into Pro Tools and Digital Performer, while Dan Blessinger engineered the Martinsound sessions. The remaining instruments were recorded at Wall’s nearby studio.

Rather than hire a 70-piece orchestra (which he did for Myst 4), Wall turned to libraries, choosing from the Vienna Symphonic Library, Project SAM for brass, SAM True Strike Orchestral Percussion library, Sonic Images sample library, Peter Siedlaczek’s Advanced Orchestra for some of the woodwinds and “a sprinkling” from the Gary Garritan Orchestral library. The result was more than 90 minutes of score (including cinematics and in-game) that was then divided into tracks that were one-and-a-half to two minutes long.

Faced with a very different, yet highly challenging composing experience on many levels, Abernethy entered Kasai‘s world at the midway mark. He and his Raleigh, N.C.-based Rednote Audio team — Jason Graves and Dave Adams — were given video and game play to fiddle with, a prequel to draw from, Doud’s samples and a basic concept delivered by Sony Entertainment Corp. From there, Abernethy and crew chopped up Doud’s samples, recorded more percussion, drums and drum hits of their own, and triggered it all with MIDI. Abernethy estimates each level of audio at about eight minutes long, “but you can’t say linear minutes because it plays all those tracks at different times. It’s almost an unlimited arrangement.”

Jack Wall (far right) conducts a percussion session for Jade Empire.

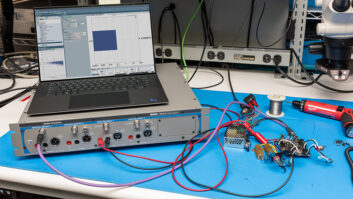

Abernethy composed on Digital Performer 4 on a Mac G4 that sits alongside an 80-channel Otari Status console, working with mostly original samples. “We were using three Mac G4s, one Dell PC, BIAS Peak, Cool Edit Pro, two E4-X2 samplers and three ASR 10s,” he explains. “We put our samples into the proprietary Sony sound tool, which has its own MIDI player, and then programmed our sequences within the tool.”

Rather than running straight to an interface, Abernethy often runs mics through vintage API 512 and Neve 1272 pre’s. “It makes a difference,” he says. “Whether gamers are really paying attention, who knows, but in the long run, the little things do add up.”

The music then split into bass, vocal and percussion parts — all MIDI files, all playing the downloadable samples. In addition to arranging these samples, Abernethy made sure that all the data fit into the PlayStation’s memory budget. The memory budget for Kasai was 800k per level using a 4:1 compression. A typical PS2 game has a total memory budget of 2 MB, with additional audio streamed from the game disc. “Some samples were 22k/16-bit, some were 6k/16-bit, so we had to pay attention to whether the samples needed better high end or if they were real low bass sounds where we could cut off the top end and use a lower sample rate to save memory,” he says. “When you’re recording a regular pop CD, you’re just trying to get the best sample rate you can; in this case, we had to really pay attention to conserving memory space and what sample rate we could use.”

That said, popular sites such as MusicForGames and GameSpot gave high marks to Rise of the Kasai‘s audio, which banished any assumptions of early MIDI-cheesiness and considerably altered the user’s experience. “This MIDI technique really changed the gameplay experience,” says Abernethy. “It was a true second-by-second adaptive soundtrack with the player — stomping around, pulling out the sword, et cetera. The music changes with each action, and you never hear the same loop twice.” How fast the gameplay and its coinciding music changes depends on the ultimate mixer — the player.

INTEGRAL INTEGRATION

While the composers are busy scoring the music — MIDI, a full orchestra, live instruments or symphonic music libraries — the rest of the audio team works with sound effects, Foley and dialog. The elements unite at the end of the process — much like they do for a feature film. But the fact that dialog cues are short, music ranges from short blips to long phrases to song clips, and effects have to pop for the youth market means that the mix becomes infinitely more complicated and nonlinear. (Look for in-depth coverage on the creation of game dialog and effects, and the implementation/programming process in upcoming issues of Mix.)

Rednote Audio’s Rod Abernathy (L) and Jason Graves

Once all audio elements are created, recorded and mixed, they join the visual elements during implementation, which comprises about 70 percent of the work. Often, composers will deliver their .WAV or MP3 files to the audio director and away they go, leaving their detailed score in the hands of one or more audio programmers.

However, many composers want more control over how their music plays. Wall provided input as to where to put certain pieces of music and pointed out when the audio did or didn’t match the story line. For Jade Empire, Wall also created custom mixes — percussion/no percussion — that were chopped up into 80 additional cinematics and placed into the game. Using a special Xbox development kit, Wall played the game at various stages and provided suggestions as to which tracks would work for different gameplay aspects and storylines.

“RPGs [role-playing games] have to be very story-driven, so it’s almost like an interactive movie,” Wall explains. “You’ll have a conversation with a character and based on that conversation, you’ll go to a different place. So the score needs to reflect what’s going on at any given time. I had pieces of paper all over my studio, noting which pieces are happy, romantic happy, then you’ve got the sad, the mystery/suspense, the dark and creepy, the haunted — the whole gamut. I could take from that list and just script the pieces into the game.”

Meanwhile, Sim mastered and edited the files and the game’s volume adjustments. BioWare’s designers assigned the music to different areas of the game and scripted specific tracks to be triggered to critical story moments. Audio coder Dan Yakielashek handled most of the transitions and crossfades from one piece of music to the next.

Chuck Doud

Photo: courtesy of Sony Computer Entertainment America

For Kasai, Abernathy and the Rednote team transferred all of their samples into Sony’s proprietary music engine, a device that allowed him to plug sounds into the tool, sequence and program. “The best thing about this tool is that it puts 99 percent of the power in the hands of the composer,” says Doud. “With a lot of other interactive music tools, the composers have to rely on a programmer on the game side and that’s always a risk. Composers complain about that all the time. Guys like Jack tend to be lucky, where they’ve got really strong support on the programming side, but that isn’t always the case. With our engine, the instructions that go out to the programmer are very minimal. Most of the work is actually done on our side, so by the time we dump the music into the game, it already knows what to look for. As a composer, that’s the kind of system that you want, but if you’re not working on one of our games, you’re screwed!”

PLUGGED-IN POST

RAM budgets, which vary depending on the delivery platform, have to be considered at nearly every stage of the game, especially during the post mix. The Xbox is currently the most powerful console, audio-wise, with Dolby Digital 5.1, a healthy amount of RAM and a built-in hard drive. PlayStation 2 carries 2 MB of audio RAM.

It takes savvy audio management skills to mix for large-scale games with massive amounts of dialog, effects and music tracks. Audio directors often have to pick their battles (so to speak!), downplaying Foley or certain ambiences to make room for more prominent features. They also have to apply higher sample rates to weapon fire and other high-priority sounds, and lower rates, say, 18 kHz for dialog and 11 kHz for far-off explosions or background noises. Format also has to be considered as each platform has its own requirements: Xbox uses 5.1-channel Dolby Digital surround; PlayStation and GameCube use Dolby Pro Logic II.

“The bulk of our post processing was done with plug-ins,” says Sim, who handled Jade Empire‘s final mix in about two weeks at BioWare’s studio, which feaures a live room for Foley and demo voiceover, a Nuendo workstation, PreSonus dual-servo preamp and Digi 001. “We used Waves and Sony Media plugs, the TC Electronic Native and the plugs that come with Nuendo. I use the L2 or Sony Waves Hammer for a lot of our hit and impact sounds and visual effect sounds to bring them a bit over the top. We did not mix the cut scenes or music for Jade in 5.1 because with 16,000 lines of dialog, space on the DVD was limited.” Lucky for Jade, Xbox offers real-time Dolby Digital encoding via the APU, which means that the unit handles the 5.1 mix itself and Sims just had to make sure the placement of the sound’s directionality was correct. Rise of Kasai didn’t require a conventional mixdown, “because we didn’t need a final mix,” says Abernethy. “The game is doing that. Like any MIDI player, you’re giving it an assignment to play things at a certain volume level. That’s what so cool about this game: You’re sort of mixing it as you play.”

A NEW GAME AHEAD

With the launch of new platforms such as the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3, the list of capabilities and the quality of audio and video will only improve. Sim notes that the compression software encoding is getting better all the time, “which allows us to make higher-quality audio while using less space and memory.”

Doud reports that in addition to the more popular streaming method, Sony will continue to use MIDI, “but instead of controlling tiny sample banks, we’ll be able to use that MIDI functionality to control full-res .WAV files. We’ll have that dynamic flexibility without having to make sacrifices on the fidelity of the music. That’s extremely exciting for me.”

Heather Johnson is a Mix assistant editor.