When producers Denzil Foster and Tommy McElroy turned in Funky Divas, En Vogue’s triple-Platinum sophomore album, to their record label, executives didn’t want to release it. “We don’t hear any singles,” chimed the suits at Atlantic/East West. “It’s okay, but it ain’t no Born to Sing” (their first album).

But the hot production team that revolutionized R&B with their fusion of hip-hop beats and soulful melodies (Club Nouveau, Timex Social Club, Tony! Toni! Toné!) knew otherwise. They wrote, arranged and produced an entire album’s worth of singles with En Vogue, and they didn’t want to replace any of them.

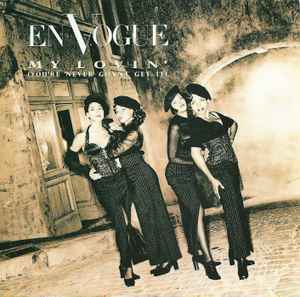

Somewhat reluctantly, the label released the album as is, and when Funky Divas‘ debut single, “My Lovin’ (You’re Never Gonna Get It),” hit radio and retail in the spring of 1992, the public proved Foster and McElroy right. The single peaked at Number 2 on Billboard‘s Hot 100 Singles chart, dominated pop and R&B radio, and kicked off a succession of five pop hits and several more dance favorites from that one album alone.

At the same time, the stunning, sexy quartet sauntered into heavy rotation on MTV, solidifying their triple-threat image of sass, style and smarts. En Vogue had all the ingredients of the ultimate vocal group: four equally strong singers, all capable of singing lead, and all with distinct personalities to conjure many a young boy’s fantasies. Foster and McElroy recruited vocalists Cindy Herron, Maxine Jones, Dawn Robinson and Terry Ellis in 1989 with this vision in mind, and as their careers developed, they became role models for later groups such as Destiny’s Child, Jade and TLC, among others.

Not only did En Vogue’s career peak with Funky Divas, but Foster and McElroy rose to become the San Francisco Bay Area’s answer to Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. Their minimalist production style — heavy on groove, hook and vocals, light on filler — brought R&B music to pop ears, and “My Lovin’” stands out as one of the most memorable examples.

For most of their careers, Foster and McElroy had worked almost exclusively at Starlight Studios, a modest facility in Richmond, Calif., christened “The Bunker” by some of its regular clients. After En Vogue hit Platinum with Born to Sing, recorded at Starlight Studios and Live Oak Studios in Berkeley, Calif., Foster and McElroy bumped things up a notch and brought the group to Fantasy Studios to record their follow-up. In the early ’90s, the popular studio hummed with nonstop activity from clients such as MC Hammer, Santana, Sammy Hagar and Chris Isaak, among others, although the En Vogue crew’s “banker’s hours” (roughly 11 a.m. to 9 p.m.) and strong work ethic didn’t allow for much socializing. “We were locked up in our own little corner of the world,” Foster says, jokingly. “We didn’t know who was coming or going until we saw another plaque on the wall!”

“My Lovin’” came together almost entirely in Fantasy’s Studio B, the smallest of the facility’s four studios, equipped with a Trident 80B, 21×26-foot recording room and a small lounge/vocal booth. They built a solid groove first. The song’s underlying, hypnotic drum beat came from a combination of E-mu SP12 and SP1200, and Akai MPC60 drum machines. “Tommy liked the hi-hat sounds that he had in his SP1200, and Denny liked the kick that he had in MPC60,” recalls engineer Steve Counter, Foster and McElroy’s engineer since the mid-’80s. “These were not the standard sounds that came with the unit; they were sounds they had sampled themselves at home or from various sources.” They recorded about six minutes of that beat, then added bass and other rhythmic elements on top. Foster created the bass line on a Korg M1. “I made a patch in the M1 that turned out to be a centerpiece,” he says. “It had a sound called ‘Pluck Bass Light.’ I took some of the pluck out of it and it sounded like a nice five-string bass. I used it for a lot of things — all the phrasing; the only thing I couldn’t do was actually pluck it!”

Aside from the vocals, the rhythmic foundation is the most crucial element of the Foster-McElroy formula, the bed upon which all other instruments are layered, and usually the inspiration for the song’s basic melody. In the case of “My Lovin’,” they had trouble coming up with a melody that matched the killer groove they had created. Foster, who handled most of the vocal arrangements, toyed around with several different ideas, but he says they all sounded “corny” or diminished the dynamic rhythm. So they set the track aside and pretty much finished the album before they revisited “My Lovin.’” By then, Foster could listen with fresh ears, and new ideas came.

“I listened to that ‘t-t-t-t’ rhythm, and then I heard this ‘da-da-da-da’ sound,” he says of the “never gonna get it” rhythm. “Then I heard sort of a teasing sound. So I hummed that, and then the girls hummed it, and I thought, ‘Okay maybe we’ve got to approach this song like you’re teasing a guy or attacking a guy. We decided to escalate from [the single] ‘Hold On’ [from Born to Sing], which was about how not to lose your man again, and have some teasing thing going on with a man, and that’s how the ‘never gonna get it’ came out. Then it became, ‘What are you never gonna give up? Oh, my lovin’.’ After that, it fell into place. We actually recorded the hook on the song, and me and Tommy moved to something else again.”

When they revisited the track, they added in a sampled guitar that they liked, fleshed out the vocals and penned the lyrics, which still hadn’t been written when En Vogue arrived at Fantasy to record vocals. “Denny would have a good idea for the hook and the verse melodies by the time the girls would come in, but he would write the lyrics right there, and then they would sing them,” says Counter. “The words you hear, those lyrics are five minutes old.”

Working off of the basic theme — the tease — Foster and En Vogue brainstormed on different lyrical ideas, this time, all revolving around the man who screwed up and the woman who ain’t gonna give it up anymore. The verse melodies came at the same time, and when they got enough elements written, they sang them.

Counter opted to mic all four singers with Telefunken Ela M 250 microphones and ran them through a vintage Neve 7198 mic/line mixer and a Teletronix LA-2A compressor to a Studer A800 2-inch tape machine. He captured their spot-on harmonies two at a time, with very little vocal stacking. “We didn’t like the sound of having every girl to a track,” says Foster. “Plus, the girls have pretty powerful voices, so we didn’t really have to do anything except double them for stereo effect.”

“If it were a three-part harmony, we’d do three parts on the left side, three parts on the right and that’s it,” adds Counter. “The more you stack them up, the more washed out they sound and you start losing presence. Denny wanted the vocals to be real present and full, so we doubled the parts and then left them alone.”

The group re-recorded lines and verses many times over to get them right, but Foster and McElroy rarely sampled vocals and Counter never had to punch in syllables or tune a vocal. (Real-time pitch-correction devices weren’t available at that time, anyway.) “We all had really good pitch, so we didn’t have a lot of bad notes and stuff,” says Foster. “The problem came from them getting hoarse or tired. We pushed them to limits that I don’t think they realized they could do, and that was the purpose. If you’re going to have these great voices, let the world know how great they really are! If you got 260 horsepower, use all of it!”

McElroy added a few extra instruments: a chunky piano, a flute run, an extra keyboard riff. Then, with the basics on tape, Foster and McElroy joined engineer Ken Kessie at Can-Am Studios in Tarzana, Calif., to mix the album. Kessie synched up two Studer A827 2-inch machines for the 30-plus tracks, then mixed down to ½-inch analog.

Working on the room’s “punchy” 56-input SSL 4000 E Series console, Kessie mixed most of the song relatively quickly, he recalls, employing Foster and McElroy’s basic formula: “punchy drums, a killer groove, a strong bass line, warm and clear vocals, and very little ambiance.”

Kessie worked closely with the duo to fine-tune the arrangement, using the console’s automation to mute various instruments during verses, bridges, raps or breakdowns. “It wasn’t like now, where I could arrange the whole song in Logic or Pro Tools,” says Foster. “It was more spontaneous. Before we got to the mix, we’d have all of the instruments playing all the way through, then start pulling stuff out to make things more dynamic.”

As a result, the arrangement, like a lot of Foster-McElroy tunes, had “lots of open space,” as Kessie recalls. “Tommy and Denny were so confident in their work; they just recorded what was needed and nothing more.” They extended this less-is-more approach to the vocals. “Back then, it seemed like every vocal had the same pitched-up/pitched-down stereo harmonizer patch,” says Kessie. “We all thought this sounded ‘un-soulful,’ so we avoided it like crazy. The En Vogue singers could really deliver and didn’t need any pitch-enhancing gear. Also, there was very little, or no vocal reverb. It’s commonplace now for dry vocals, but we were one of the pioneers.”

Only on rare occasions did they make radical changes at the 11th hour. The big band-influenced breakdown in “My Lovin’” was one of those times; they recorded and spliced it in after the mix was finished!

Classic Tracks: The Mamas & The Papas’ “California Dreamin’”

The original breakdown had more of a “party” theme and didn’t fit the song, they decided. They wanted something more dynamic that would show off the group’s harmony prowess in a big way. Foster, busy with some other last-minute details, passed the baton to his partner. McElroy went into the piano booth, alone, and toyed around with Andrews Sisters-style melodies.

“I remembered the chords I used to play in the big bands in high school,” says McElroy, who worked as a jazz musician before meeting Foster in the early ’80s. “Denny gave me a rhythm, and I took that and came up with a chromatic thing with a 4th, 7th, 9th, and a dominant 7th chord, and then stacked them. When I played it for Denny, he took one or two notes out and worked on it with the girls for, like, 10 minutes and started recording. I thought, ‘Aw, man! I did it!’”

It worked like a charm. “At that time, they were so in tune and in tune with us,” says Foster. “They were like an instrument that you could just pick up and play. Once they heard [the breakdown], they hit the notes like horn players. I don’t even know what chord they started on, it just worked, and then it went easily right back into the song!” McElroy adds that as soon as En Vogue sang that part, “It was like real magic. I was so happy and proud of everybody. That became the highlight of the song.”

Kessie assembled the final version of “My Lovin’” using one of his new finds: a 4-channel Digidesign Sound Tools system, the predecessor to Pro Tools. He captured the original mix and the new breakdown section into a computer, “and with the miracle of digital crossfades, was able to smoothly blend the two sections recorded months apart,” he says. “Doing the same splices on half-inch analog would have been nearly impossible. I was nervous at the time because the analog-to-digital conversion lost some quality, but it goes to show that a great song trumps engineering anytime.”

When they listened back to the final mix, they knew they had something special. Foster lit up, Kessie says. They knew that all of the struggle would pay off, and it did, in a huge way! Aside from massive sales, “My Lovin’ (You’re Never Gonna Get It)” solidified the message that Foster and McElroy had wanted to convey all along with En Vogue. “That song illustrated that there were four women in the group that could sing lead, as opposed to just Cindy and Terry, who were featured more prominently on their last album,” says Foster. “It showed that every one of them could step up and be featured and be a favorite. Everybody could identify with someone from En Vogue.”