This Classic Tracks is from the January 2003 issue of Mix.

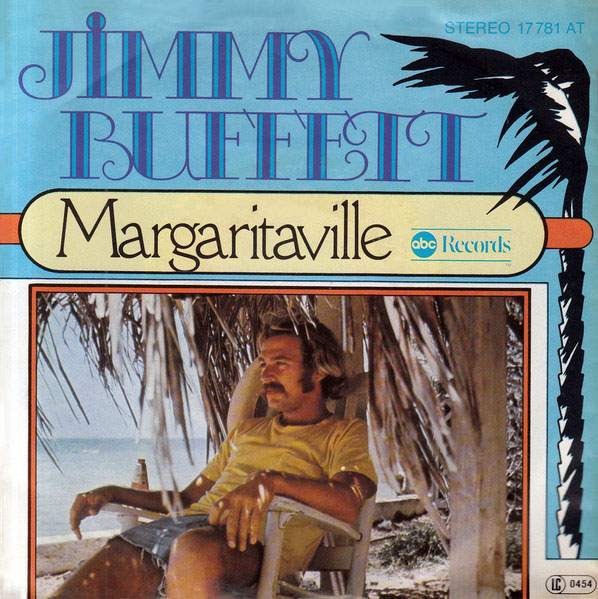

Few songs have defined an artist, an era and an attitude quite like Jimmy Buffett’s “Margaritaville,” released in January 1977. The song continues to be the national anthem for generations of college kids on spring break, burnt-out stockbrokers and wishful thinkers who long to leave careers behind and let their biggest worry be which beach to sleep on that night. Buffet himself has turned the song into a kind of theme park—the day-in-the-life-of-a-beach-bum chronicle has been the cornerstone of an empire that now includes bars, books, T-shirts and other “Parrothead” paraphernalia always clearly in evidence at the Mardi Gras-like concerts that Buffett continues to sell out every year coast to coast.

Maybe Buffett had an inkling of what the song would come to mean for him and others. It took him several days to write, much longer than his usual musical gestation period. “He’d often write a song in the morning and we were recording it in the afternoon,” recalls Norbert Putnam, producer for Margaritaville and several other Buffett albums, as well as a huge discography of other artists including Dan Fogelberg, Joan Baez and New Riders of the Purple Sage. “He had this one kicking around for a while. He’d tell me about it, that it was a day in his life, and I’m thinking, ‘Oh, like The Beatles—‘A Day In the Life.’ I didn’t know what to expect.”

Putnam met Buffett in 1976 in Nashville, where Putnam and David Briggs—who had both traveled north from Muscle Shoals years earlier to become part of the city’s 1970s iteration of the A-team musicians—owned Quadrafonic Recording Studios. Quadrafonic had been a pop oasis in Nashville, hosting sessions for the likes of Linda Ronstadt and Paul Simon, allowing Putnam to establish his credentials as a pop producer with artists such as Joan Baez, whose “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” gave both the artist and producer their first Top 10 pop single.

Buffett migrated to Nashville in the 1960s to pursue a record deal. His second solo record earned him some notoriety for the song “Why Don’t We Get Drunk,” because that title question continues in the chorus “…and screw”; a little extreme for Music Row tastes at the time. By the early 1970s, Buffett was living in Key West, a place better suited to his personality and artistry, signed to ABC/Dunhill Records and working with his Coral Reefer Band. Putnam recalls that it was a label executive who suggested pairing him and Buffett, whom Putnam recalls having first met when the singer was working a second job as a freelancer, writing concert reviews for Billboard in Nashville. “He came into Quadrafonic to do an interview with Jerry Jeff Walker, I think,” says Putnam. “He had been working with [producer] Don Gant in Nashville, and they kind of had a hit with ‘Come Monday.’ They made that in Nashville with Nashville session guys and The Jordanaires—but it wasn’t who Jimmy really was. One night, he approached me at Julian’s [a legendary upscale Nashville watering hole of the era] and we talked. He said that the Coral Reefer Band was more like the Rolling Stones than the Grand Ole Opry, and after I went to a concert of his, I knew he was right. Actually, they were like the Stones on acid. They were playing ‘Come Monday,’ which was a ballad, with power rock chords.”

Putnam decided that Miami’s Criteria Studios was the place to bring Buffett, given the singer’s proclivity for the seashore and the studio’s elevated presence as home to the Bee Gees and records for Eric Clapton, The Eagles and many other top artists and producers. When they arrived in Miami that summer with Buffett’s band, Putnam and Buffett quickly agreed on a work schedule: In the studio at 11 a.m.; work on whatever song Buffett had finished that morning; out at 5 p.m.; head to Buffett’s new 33-foot sailboat; pop in a cassette of the day’s work and listen. “For that album, we were trying to get the rhythms and the vibe to match the rhythm of the ocean waves against the boat,” says Putnam. “Sounds crazy, but it was working. We were getting a vibe for the record.”

What Putnam was less sure about was a single. He was pleased with Buffett’s songs and liked his choice of covers, such as Steve Goodman’s “Banana Republic,” but he still hadn’t heard the song that would put the album over the top. Then, during the second week of recording, Buffett walked into the large tracking room at Criteria and announced to Putnam that he had finished the day-in-the-life song. “It was called ‘Margaritaville,’ and I wasn’t crazy about the title,” says Putnam. “I was thinking that it had these sort of jazz-hipster overtones like ‘coolsville’ or something like that. But when he played it, me and the band knew instantly that this was the song. This was the single. This was it. It wasn’t a song — it was a three-minute screenplay.”

Jimmy Buffett Live in 1998: Turning Manhattan into Margaritaville

Putnam and engineer Marty Lewis recorded the track just as they had the others: drums, bass, guitars and keyboards all set up as an ensemble, with Buffett singing his lead vocals live into a Neumann U87. (Most of those live vocals were kept for the finished version, too.) The recording was through an MCI 500 Series console to an MCI JH-24 multitrack deck running at 30 ips and no noise reduction, because as Putnam notes, “Marty really liked to push the tape a lot.” However, Putnam, knowing how critical “Margaritaville” was to the project, felt that he wasn’t getting the groove from the band drummer, Michael Gardner. He asked Kenny Buttrey, one of Nashville’s premier session players, whom Putnam had ostensibly brought down to play percussion (but also as a backup in case just that kind of situation arose), to fill in on drums.

“Jimmy loved working with his own band and I understood and respected that,” says Putnam, “but I knew I wanted a few seasoned session guys there, too. Road drummers almost never work as well with headphones as experienced studio guys.” The switch assured that “Margaritaville” was nailed in three takes. Most of the musical moves on the track, such as Mike Utley’s little clavichord filigree that sets up Buffett’s first vocal entry, were made up on the spot. There were few overdubs; Utley was surrounded by a grand piano, a clavichord and a Fender Rhodes electric piano, and switched between them on the fly, as he did in concert. “I would say that we had cut the track, virtually complete, within 30 minutes of Jimmy playing the song for us,” says Putnam.

The tapes were taken back to Quadrafonic in Nashville for sweetening, fixing and mixing. Putnam and Utley wrote the string parts for the album’s tracks, as well as the flute and recorder parts played by Billy Puett using, as he recalls, a bottle of Cristal champagne as a muse. Several overdubs had also been done in Miami, such as a marimba on “Margaritaville”—part of Putnam’s attempt to give Buffett a distinctive sound. “I was trying to come up with the sounds that would define him, and my ideas were all Hollywood clichés—marimbas, congas, a ship’s bell. But you know what? They worked. It might have seemed a little corny, but that’s what Jimmy was about: creating characters the same way Hollywood does.”

Classic Tracks: Gary Wright’s “Dream Weaver”

There were a few vocal punches done at Quadrafonic by Buffett, but not on “Margaritaville,” following Putnam’s desire to keep the take’s emotion dominant over an occasional pitch squib. Buffett did his harmony vocal overdubs there. To get around the singer’s aversion to headphones, Putnam set up a pair of Big Red monitors loaded with 15-inch Altec speakers about a foot apart and just behind Buffett’s ears. “It’s an interesting trick,” he says. “You can really have the singer feel like he hears it all perfectly without headphones but you have to place them carefully, and sometimes we’d put the bass out of phase to avoid that blowing back into the microphone.” The vocal passed through an LA-2A compressor and little else in the way of processing.

The mix was also done at Quadrafonic, on the studio’s MCI 500 Series console, which had an early version of MCI chief Jeep Harned’s first automation system onboard. Putnam, like everyone else at the time, was fascinated by the prospect of automation, but he also missed the warmth of the studio’s previous Quadrafonic 8 console. With that in mind, he asked Paul Buff, then of Allison Research and forerunner to gate-maker Kepex, for advice. Buff suggested that a 1940s Bell Labs design for a transformerless micpre might warm it up and still allow the automation to not affect transient response. The solution worked so well that Putnam says Harned incorporated it into future versions of the console.

The mix was done over Big Reds with Mastering Lab crossovers and loaded with Altec 604E speakers, which Putnam describes as “awful, but if you could make it sound good on those—and good was the best you’d ever get—then you knew it would sound great on record.”

“Margaritaville” was a surprise hit in the spring of 1977, making it all the way to Number 8 on the Billboard Singles chart and propelling the Changes In Latitudes, Changes In Attitudes album to Number 12. When you factor in the many compilation and live releases through the years, “Margaritaville” has now sold close to 50 million copies—not bad! However, as Putnam noted, the song’s longevity can be attributed to its accessible narrative as much as anything else: “As I’ve told Jimmy more than a few times, he and I made good records together, but we would have made even better movies.”