As fate would have it, the first band I ever saw perform live (outside of at local dances) was the Staple Singers, opening for The Doors at Madison Square Garden in January 1969. I’d never heard a note by them before that night, and even though the mostly teenage audience was largely inattentive during The Staples’ 30-minute set, I was both charmed by them and engrossed in their set. I had been listening to a lot of old country blues in between my Cream and Jefferson Airplane records, and it was clear to me that The Staples were part of that line that stretched from the Mississippi Delta in the ’20s, shot through Chicago in the ’40s and ’50s, and then changed the face of rock ‘n’ roll in the ’60s. The Staples weren’t really a blues group, although Roebuck “Pops” Staples’ slinky guitar lines obviously came from that world. But their harmonies were straight from the Southern Baptist church; there were dominant elements of secular ’60s R&B in there, and a few of their songs that night had socially conscious lyrics. Lead singer Mavis Staples might not have had the rep of Aretha, but she had incredible pipes and passion to spare; another sister of the church possessed by the Holy Spirit.

As fate would have it, the first band I ever saw perform live (outside of at local dances) was the Staple Singers, opening for The Doors at Madison Square Garden in January 1969. I’d never heard a note by them before that night, and even though the mostly teenage audience was largely inattentive during The Staples’ 30-minute set, I was both charmed by them and engrossed in their set. I had been listening to a lot of old country blues in between my Cream and Jefferson Airplane records, and it was clear to me that The Staples were part of that line that stretched from the Mississippi Delta in the ’20s, shot through Chicago in the ’40s and ’50s, and then changed the face of rock ‘n’ roll in the ’60s. The Staples weren’t really a blues group, although Roebuck “Pops” Staples’ slinky guitar lines obviously came from that world. But their harmonies were straight from the Southern Baptist church; there were dominant elements of secular ’60s R&B in there, and a few of their songs that night had socially conscious lyrics. Lead singer Mavis Staples might not have had the rep of Aretha, but she had incredible pipes and passion to spare; another sister of the church possessed by the Holy Spirit.

I didn’t know it then, but the already-veteran Staples were just entering their Golden Era around this time. Pops Staples was born in 1915 in Winoma, Miss., where he heard the blues of Charley Patton, Ma Rainey, Son House and others, and was inspired to take up the guitar himself. At the age of 16, he joined a gospel group, the Golden Trumpets, and stopped playing secular music completely. “I was a Christian man,” he said. “I figured blues wasn’t the right field for me. My family was a real religious family. There were 14 of us. In the evening, when we used to get through working in the fields picking cotton, we didn’t have no amusement but to sing to ourselves. We didn’t have no radio, no television, nothing like that. That’s the way my family got started singing.” In 1935, he joined the huge exodus of African-Americans who moved from Mississippi to Chicago, hoping to find a better life for him, his wife Oceola and their first child Cleotha. His brother, Rev. Chester Staples, was already in Chicago, and Roebuck found a home there for his music. Three other children followed Cleotha — son Pervis and daughters Yvonne and Mavis — and Pops schooled each of them in harmony singing, just as his own father had taught him and his siblings. By 1953, the Staples family had earned a considerable reputation in Chicago for their exquisite harmonies in church, and they cut their first sides for the local United Records; that led to them getting a national contract from Chicago-based VeeJay Records. In 1956, they recorded one of the first million-selling gospel singles — “Uncloudy Day,” written by Pops. Other hits followed, including “Too Close,” “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” and “This May Be the Last Time,” a song that was, frankly, later ripped off by the Rolling Stones. In the early ’60s, they put out albums on Riverside and Epic and were embraced as part of the folk boom. Though still firmly rooted in gospel music, some of their songs started reflecting the socio-political currents of the times, as well. Pops wrote “Why (Am I Treated So Bad)” in response to racial unrest surrounding early efforts to desegregate schools in the South, and after meeting Martin Luther King and watching him speak in Birmingham, Pops supposedly told his family, “If he can preach this, we can sing it.” In 1967, The Staples even cut a version of Stephen Stills’ “For What It’s Worth,” giving it a soulful reading Stills’ Buffalo Springfield couldn’t have possibly imagined; it even made the pop charts briefly.

The following year, the Staples Singers changed gears again. They signed with Memphis-based Stax Records and began cutting albums there with Booker T. & The MGs’ guitarist Steve Cropper producing and MGs’ bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn and drummer Al Jackson Jr. laying down funky Memphis soul grooves behind the singers. After two albums produced by Cropper (Soul Folk in Action contained their amazing version of “The Weight”), they came under the aegis of Stax producer/executive Al Bell, who wanted to turn the group in a slightly more commercial direction, just as he’d done with Isaac Hayes and Carla Thomas.

His first decision regarding the group was to have their basic tracks recorded at Muscle Shoals Sound in Alabama, using the extraordinary Muscle Shoals rhythm section — Roger Hawkins on drums, Barry Beckett on keyboards, David Hood on bass and Eddie Hinton on rhythm guitar. Playing additional guitar and a whole slew of other instruments, including harmonica and keyboards, was a young musician/engineer named Terry Manning, who was an engineer/musician working at Ardent Studio in Memphis.

By late 1970, when The Staples’ cut their first record with Al Bell, The Staple Swingers, Ardent had already developed a reputation as the best-equipped studio in Memphis, and Manning was regarded as one of the city’s finest engineers. A native of El Paso, Texas, Manning had played guitar with Bobby Fuller while still a teenager, even appearing on the original version of Fuller’s classic “I Fought the Law.” Fuller moved to L.A. to pursue his career (there, he re-cut “I Fought the Law”; it was that version that became the national hit), and Manning’s minister father moved his family to Memphis, much to Terry’s delight — he’d been smitten by the Memphis R&B of artists such as Rufus Thomas and The Mar-Keys (which included Steve Cropper and Duck Dunn).

“So at a very young age — still in high school,” Manning relates, “I walked into Stax Studio with a guitar in my hand and said, ‘I’m here to work.’ And those crazy guys said, ‘Okay, what do you do? We’ll put you to work.’ Obviously, that would not happen today,” he says with a chuckle. “I said, ‘I sing, I write, I play. I’ll do anything!’ So, I started copying tapes and sweeping up the floor.” Manning had been messing with recorders since he was nine and always had an interest in recording, so he was an eager student at Stax. “Then, the band I played in locally — called Bobby & The Originals — recorded at John Fry’s home studio, so I started hanging out there. John, who was just out of high school, had a studio in his parents’ house, and I consider that the original Ardent. And a lot of really cool things were recorded there — some rockabilly things that are not that well-known nationally, but were popular in Memphis, were cut there; all sorts of things. When I first went there was around ’64. We recorded there for a while and John had already been there for some time, and then he wanted to expand to a real studio building, so he found this place that was at 1457 National Street. It was half of this big building that stretched over a whole block. He built Ardent in there, and the other half of the building was a Bible bookstore. That was 1966, and that was the first real Ardent commercial studio.

“After the studio moved,” Manning continues, “I started working over there and a lot of Stax business came there. We had the first 4-track — a Scully — in the South. So that’s one reason Stax people came over to work there, and that’s how the Staple Singers would have come over there. Steve Cropper would cut [‘Dock of the Bay’] at Stax and then bring it to Ardent, and we’d mix it there. Or [Memphis producer] Willie Mitchell would cut these tracks of Al Green and Ann Peebles and people like that at Hi’s studio, and then he’d bring it to Ardent to mix. I guess people still do that: ‘We’ve got to get Bob Clearmountain to mix this…’ R&B acts from all over — New Orleans, Chicago, Philly, Detroit — would get me to mix. I got to work on all these records that I now look back on as these great, classic records. At the time, they were just more sessions — I mean I always loved them, but we didn’t know they were so great that we’d be hearing them still 30 years later.”

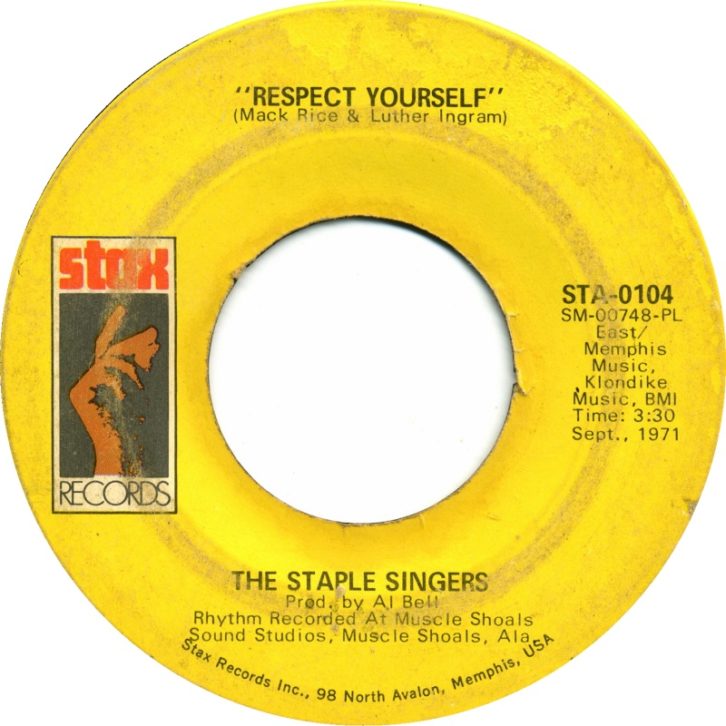

So Manning played on and mixed The Staple Swingers LP, which produced three hits for the group, stretching from December ’70 through the summer of ’71: “Heavy Makes You Happy,” “Love Is Plentiful” and “You’ve Got to Earn It.” Al Bell knew he’d hit on something with the group, so the next album, begun in the summer of ’71, was made in much the same fashion as the previous one: basic tracks cut in Muscle Shoals, with Jerry Masters engineering, and then overdubs and mixing at Ardent, with Manning engineering and adding a number of instrumental parts himself. Bell found a fantastic bunch of songs for the group to record this time out, including his own “I’ll Take You There,” Carl Smith and Marshall Jones’ “We the People,” and this month’s Classic Track, “Respect Yourself,” penned by veteran songsmiths Mack Rice and Luther Ingram. “Respect Yourself” was a perfect vehicle for the Staple Singers — it featured alternating lead vocals by Pops and Mavis, a slinky bass-drums-rhythm guitar-Wurlitzer electric piano groove set up by the Muscle Shoals gang, and lyrics that decried racism (“take your sheet off your face, boy, it’s a brand new day”), as it spoke to the rising black pride movement. Its “message” was in its title really.

Tracking sessions at Muscle Shoals Sound were always relatively straightforward in those days, Jerry Masters remembers. It was a “hot” studio at the time, and there were often sessions going day and night. “We were like a track factory,” he says. “Sometimes we didn’t even know who the artist was, because they weren’t around for the tracks. Then later we’d hear a song on the radio and we’d say, ‘Well I’ll be darned, that’s who that was!’”

A former casket factory, the studio had a wooden floor with a basement underneath, “and I think that had a lot to do with the ambience in the room,” Masters says. “By the time we worked with The Staples, we had built a drum booth and that really made our drums sound great.” The control room was equipped with a custom Dan Flickenger console and a new MCI 16-track recorder. To capture Roger Hawkins’ drums, Masters used a combination of close miking and overheads: “I was using [Neumann] 87s on the overheads, and dynamics on the tom-toms and the snare. I had a KM84 on the hi-hat and an RE20 on the kick.” For David Hood’s always-dynamic bass lines, Masters mostly used a direct signal. “David’s amp was right there by the control room,” Masters says, “and when they’d be running down a song, he’d have his amp on while they were getting the song down. But when we’d start recording, sometimes he’d turn his amp off. Occasionally, we’d put a little amp in [the sound]. As a bassist myself, the bass was always real important to me. On Barry Beckett’s Wurlitzer, we put this cheap, dynamic Electro-Voice mic; I can’t recall the model number.”

Classic Tracks: The Righteous Brothers’ “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling”

Masters recalls The Staples working closely with Al Bell on the arrangements of the songs — “finding the right key for Mavis, where to put the choruses and such” — though only Mavis was involved in the basic tracks. As Terry Manning, who was down at Muscle Shoals primarily as an extra guitar player, recalls, “Mavis would do a rough guide track, singing behind some baffling or in a separate little booth to help them get the feel of it. On some occasions, we’d later take some of those guide vocals and we’d have to use them, they were so good. And the musicians were playing off that feel she was getting, so it was a great collaboration.

“Al was very much the producer in charge,” he continues. “Al was not necessarily a musician who could pick up a guitar and play a c-minor diminished and say, ‘This is what I want.’ But he knew how to guide musicians into getting the feel and the sound he wanted, and he guided the arrangements. Of course, the Muscle Shoals guys were great musicians and used to playing together; they’d been on many, many hits already, so they knew what to do and they would arrange themselves to a large extent.

“Still, on this particular album, Al and I talked a lot about all the different styles we wanted to incorporate. I was trying to bring in some rock elements — fuzz tone and various things. And Al was trying to bring in a Jamaican feel. Not long before that, he’d been on a trip to Montego Bay and he’d heard some of the early reggae and he brought that back with him: ‘We need to get this feeling in with the R&B and the funk and the rock.’ That may sound a bit grandiose because maybe you listen to that and think, ‘It’s just the Memphis sound, it’s just R&B.” But it’s not. It was a big thing to us at the time. I can hear Jamaican ska type of jumps that are on the drums, especially on ‘I’ll Take You There’ — that off-beat, not all the way to reggae, mixed with R&B.”

When the basic tracks had been completed, the action shifted to Ardent, where overdubs were cut on a 3M M-56 16-track through their custom Auditronics board. Manning says that Mavis Staples’ lead vocals were typically comped from three or four run-throughs of a tune, “and nearly every take she did was great. She’s amazing, probably one of the top three artists I’ve ever worked with.” Manning used a U87 through a UA 1176 tube compressor for those vocals (and also used a U87 on Pops Staples’ guitar amp). After Mavis’ lead was in place, the background vocals — also including Mavis — would be cut, the singers usually grouped around a single U87 (or on occasion, a U67). Sometimes he would double-track the backgrounds to reinforce certain sections of a song.

Manning was fond of adding little instrumental touches to the records he worked on, and Bell encouraged him to experiment. On “Respect Yourself,” the most striking additions are the soulful blasts of the Memphis Horns, led by Andrew Love and Wayne Jackson, and Manning’s prominent Moog synthesizer line — nearly unheard of on an R&B record in those days. “The Memphis Horns really did their own arrangements for the most part,” Manning says, “but on that song, I had some ideas, too, so I came up with the arrangement in conjunction with them. I had the one line [he sings] ‘da-da-da-dit-dat-a-dat-a’ for the end; that was something I wanted to get on there. And I’d pre-done that on the track before the horns came in. You see, I’d just gotten this Moog synthesizer. I had been up to meet Robert Moog up in Trumansburg, New York, and under his tutelage I’d learned a bit about his synthesizer.” Manning bought one from Moog, and even managed to snare the keyboard controller that The Beatles had used on Abbey Road (after they returned it to Moog, mistakenly believing that because the oscillators were out of tune, that it was somehow faulty). The Staples were the first group Manning used it with. “We were working on that album that had ‘Heavy Makes You Happy,’ and I used the Moog to put these little twinkly sounds and some sort of horn-like sounds in the background.” On “Respect Yourself,” Manning used the synth as a guide track for the horn line he envisioned, but then he and Bell decided to keep the synth as a prominent element in the mix.

As far as the mix was concerned, Manning left both the instruments and the vocals fairly natural-sounding, adding some judicious EMT reverb here and there (though not as much on that track as on some others) and various other outboard tools, including Pultec and Langevin EQs.

“Respect Yourself” was released as a single in the fall of 1971, and it quickly became The Staples’ biggest hit up to that point, reaching Number Two on the R&B charts and Number 12 on the pop charts. Bell and the group completed the rest of the album Be Altitude: Respect Yourself after the single was already a hit. At Ardent, this finishing work coincided with the studio’s move to a new address on Madison Street in Memphis, where it resides to this day. With radio hungry for more Staples, a second single, “I’ll Take You There” (which features one of David Hood’s all-time great bass lines) came out in the spring of 1972 and became one of The Staples’ two Number One pop hits. (The other was “Let’s Do It Again” in 1975.) Though The Staples would never ascend to the top of the pop charts again, they continued to score R&B hits for many years, and both as a group and on solo records by Pops and Mavis Staples, they continued to make great albums that deftly mixed spiritual and social concerns.