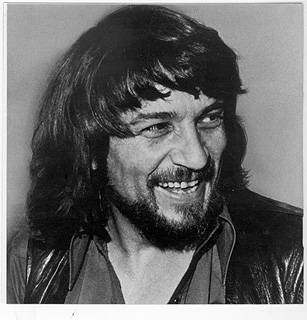

This month’s “Classic Track,” “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way,” is on Waylon Jennings’ Dreaming My Dreams, the third album he recorded in the studio owned by his friend and fellow Outlaw Tompall Glaser, and the only record he made with legendary engineer/producer Cowboy Jack Clement.

“It was my concept of Waylon Jennings,” Clement says of Dreaming My Dreams. “More earthy, and where he plays guitar himself rather than somebody else playing. He played some nice guitar on that album. He had a sound and a style. When Chet Atkins and some other people produced Waylon, someone else would play guitar and he would just sing. I heard him live and I knew that his real essence was playing guitar and singing at the same time.”

“Jack thought my voice and guitar were one and the same,” Jennings wrote in his 1996 autobiography, Waylon (written with musician/journalist Lenny Kaye). “They were a matched set. Coming from a guy who often said he was a sucker for good voices…that was high praise for my guitar…and when he got to mixing, Jack acted on the music, making it more theatrical, giving it a mystique. It sounded real strange to me when I first heard it back, but I liked it and went with it.”

“Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way” definitely has that “mystique.” The combination of layered guitars, thumping bass drum, a roomy reverb sound on Jennings magnificent voice and the singer’s clever original lyrics all create a very un-Nashville song that honors Hank Williams, Jennings’ first musical influence, and takes a tough stand against the status quo.

It’s the same old tune, fiddle and guitar

Where do we take it from here?

Rhinestone suits and new shiny cars

It’s been the same way for years…we need a change

Somebody told me when I came to Nashville,

Son you finally got it made

Old Hank made it here

We’re all sure that you will

But I don’t think that Hank done it this a’way…

Though Jennings taught himself to play guitar listening to “Old Hank” on country radio, his professional career began with early rock ’n’ roll. He was working as a DJ in Lubbock, Texas, when he met his close friend Buddy Holly. Holly produced some of Jennings’ earliest recordings, and in 1959 he asked Jennings (then age 21) to put down his Telecaster, learn the bass guitar and join the Winter Dance Party package tour, which included several other performers.

The rest is one of the saddest, best-known stories in rock ’n’ roll: On “The Day the Music Died,” February 3, 1959, Holly was tired of the frozen confines of a tour bus and chartered a plane to take his band from Clear Lake, Iowa, to Fargo, N.D. Jennings was initially offered a seat on the plane, but gave his place to tour-mate J.P. Richardson (aka, The Big Bopper), who had been ill and dreaded spending another night on a cold bus.

Jennings wrote in Waylon that before leaving for the airport, Holly poked fun at Jennings, accusing his new bass player of being afraid to fly. Jennings wrote: “’Well,’ he said, grinning, ‘I hope your damned bus freezes up again.’ I said, ‘Well, I hope your ol’ plane crashes.’”

After Holly’s plane went down, killing him, Ritchie Valens, The Big Bopper and the pilot, Jennings was emotionally devastated by the loss of his friend and unsettled by feelings of guilt over the events leading up to the crash. He stayed away from music for a while, and then decided to go back to radio. He wrote later that at that time, he had “no intention of ever playing another note.” But restless as he was, work in Texas was hard to come by and hard to keep, and he ended up moving to Arizona, and playing out to earn a living.

Jennings became a regular performer at a nightclub called J.D.’s in Phoenix. He signed a deal with A&M and scored a few hits regionally. In 1965, Nashville-based musicians Duane Eddy and Bobby Bare heard Jennings and helped convince Chet Atkins to sign Jennings to RCA. Next stop, Nashville.

While making country albums for RCA, Jennings was finally coming out of the dark cloud he’d been under since Holly’s death. He developed a stronger sense of his own sound and took increasing control over his own production. Albums such as Lonesome, On’ry and Mean and Honky Tonk Heroes were made in RCA Studio B under Atkins’ supervision, albeit with an increasingly artist-driven approach.

In 1974, Jennings was still with RCA, but he began making his albums in Glaser Sound Studios, which he dubbed “Hillbilly Central.” The studio was situated in the upper floor of an office building and was operated by a young engineer named Kyle Lehning.

Lehning says that the first time he met Jennings, the country star showed up at the studio with his road band, ready to record, completely without warning: “The first record we made in this studio was This Time,” Lehning says, “which included the song by the same name; it was his first Number One single. The first time I met him, I was sitting in the studio, playing a Wurlitzer electric piano through my wah wah pedal into a Fender amplifier. Waylon walked in the door, and I looked at him, and the very first thing he said to me was, ‘I hate those things.’

“I immediately turned it off, and he said, ‘We’re in here to record. This is the band.’ Back in those days, the studio was set up and ready to go. We had a drum kit set up; we had everything miked. They weren’t dragging in a lot of equipment off the road because all the amps and everything were already there. They basically plugged in, and in short order we were recording.

“The very first song we recorded was a J.J. Cale song called ‘Louisiana Ladies,’” Lehning continues, “and being the young punk that I was, during the playback of that song, while the band was at lunch, I went back into the studio, turned back on the piano and the amplifier, and started playing piano through the wah wah pedal to the track they had just recorded. Then Waylon came back, and I thought, ‘Uh oh, this is not going to go well.’ And he said, ‘Hey, come in here and show me how to run this tape machine and put that on this record.’

“That’s the kind of guy he was. He was completely unfettered. If he liked something, if it felt right, that’s what you did. That first album, This Time, Willie Nelson produced. It took about a week to make it. The second of the three albums I made with Waylon, Ramblin’ Man, Waylon basically produced it. That’s the one with ‘Amanda.’ That took about two weeks.”

After Ramblin’ Man, Jennings and band went back into Glaser Sound Studios with Clement to start Dreaming My Dreams. This record took seven months. And the sessions got off to a rousing start: “I think I had maybe seen Jack Clement a couple of times before this, but I had never worked with him and had never really met him,” Lehning says. “He came in the studio the very first night that we recorded. There was a producer’s desk right next to the console, and he put a bottle of Jack Daniels down there and drank what looked to me to be about half of this fifth of whiskey. I thought, ‘This is going to be interesting.’ Then he lit up a couple of joints, smoked those.

“There was a great big blue talkback button right there on the producer’s desk. Waylon and the band would start a song, and Jack would hit the talkback button and say, ‘Muuuuuuuuuuuuh,’ and I would lift his hand off the talkback button.

“The guys all threw their headphones off and looked at me like, ‘What the hell is going on?’ And I would look at them and shake my head. So they started the next take, and he did it again. Waylon jumps up, and says, ‘This isn’t going to work, Hoss,’ and they took Jack home. That was day one. But after that, nothing like that ever happened again. Jack was totally cool.”

On the whole, the Dreaming My Dreams sessions were cut live. Lehning had Ritchie Albright’s drum kit set up in a booth. Charles Cochran sat in front of the booth at the grand piano, with Duke Goff (bass guitar) and any guitar players (there were several guest guitarists on the album) arranged next to the piano.

“The studio was small, so there wasn’t a lot of space between places,” Lehning says, “and Waylon was at the center of all of this, playing electric guitar and singing live vocals into a Neumann U47 FET. Sometimes he would fix a vocal later, but sometimes it would be that live vocal on the track. The vocal chain would have been the preamp in the Flickinger console through an LA-2A and the FET U47.

“We had a lot of extra instruments around the studio, as well,” Lehning continues. “[Waylon] would actually play my electric 12-string from time to time and run it through his Maestro Phaser—though mostly he would play his old leather Telecaster. And [pedal steel player Ralph] Mooney kept everything moving in a really sweet, gentle kind of way. He would always ask just the right questions to push things in the right kind of way.”

The songs were captured to an MCI 16-track machine, but the project also made use of the studio’s Scully 2-track. “Sometimes we would use tape delay into the [EMT] plate,” Lehning says. “We had a lot of tape machines, and we even had an 8-track that I would use for slap, things like that. Ah, the good old days!”

Lehning also has fond memories of the Flickinger board: “That console sounded outrageous,” he says. “Dan Flickinger was a guy who was way ahead of his time. He built these really interesting Class-A consoles; they were transistors, but they were Class-A. The Glasers had a 20-input console, and it was huge—one of those big, heavyweight aircraft carrier–sized consoles with a big meter bridge where I could place the KLH monitors.”

Outboard processing gear at Glaser Sound included UREI 1176 and LA-2A compression, and a Pandora digital delay that Lehning says may have been used on this album (“but definitely not on vocals”). The studio was fitted with JBL 4320 mains, but Lehning says he and Clement mostly mixed on that pair of KLH Model 6s.

It was during the mix that “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way” took on the “real strange” quality that Jennings acknowledged set Clement’s production apart from other country recordings of the time.

“I took that song in a different direction while [Waylon] was away one night,” Clement recalls. “I’ll do that—get in there and experiment—and this was one that I messed with. We cut the track, and then some time later I put my own rhythm guitar part on it, and it wound up different than how it started. Waylon loved it, and that’s how the record ended up.”

“Hank” ended up being Clement’s favorite track on the album, as well as a fan favorite: It reached Number One on the Billboard Country Singles chart, and Dreaming My Dreams was a Number One country album. Clement and Jennings never worked together again officially, but they remained personal and musical friends.

Lehning left Glaser’s studio after Dreaming My Dreams to become an independent engineer/producer. He went on to tremendous success with artists such as England Dan and John Ford Coley, George Jones, Ronnie Milsap and Randy Travis, whom he’s produced regularly since 1986.

Jennings followed Dreaming My Dreams with the seminal Wanted: The Outlaws collection that also featured his wife, Jessi Coulter, and friends Glaser and Willie Nelson. All told, Jennings cut more than 50 albums in a nearly 40-year career. Jennings suffered from RSI late in his life, and was no longer able to play guitar when Mix interviewed him in 1998. He also suffered from diabetes and died of complications of that disease in 2002.

“Dreaming My Dreams is my favorite album I’ve ever done,” Jennings wrote in ’96. “Whether it was Clement experimenting, or the sense of possibility I felt settling into Tompall’s upstairs studio, surrounded by friends…it was a special moment in time, hanging at Tompall’s, being brothers.”