Growing up in Queens, N.Y., Irwin Fisch gave little thought to a career in music. After high school, he earned a degree in journalism from Syracuse University before heading back to town, where he’s spent his entire life. Little by little Fisch found himself drawn into the musical life of Manhattan. “I played in bands through college,” he says. “In the early ’80s I toured with the folk artist Tom Rush, and Peter Allen. I kind of stumbled into arranging and writing as an outgrowth of the work I got as a player.

“I really took to the synth revolution when it hit and have kept a lot of the ancient keyboards I picked up when they were current,” he continues. “Lots of these axes find their way onto many of my tracks to this day, including an old Voyetra 8, my Prophet 5 and a pair of Roland Super Jupiters. The onset of MIDI actually had a lot to do with my getting deeper into composing and arranging. Sequencing led to the democratization of keyboard playing. Practically anyone could slow down the tempo and play his or her own keyboard parts, and work for session keyboardists like me dried up. I had to work, so I turned to the other areas of the business.”

Fisch has cultivated a longtime relationship with jingle house Three Tree, whose principals include legendary New York jingle writer/singer Jake Holmes. “I’ve written jingles exclusively for them for the last decade or so, since they formed as 4/4,” Fisch says. I make about half of my living doing jingle work. The other half of my income comes from film scoring, primarily for movie-of-the-week projects.” The two halves are not as different as they may once have been. According to Fisch, “The jingle business has changed. It was built on songs, but there’s a feeling in the ad agencies that songs are somewhat passe. Scoring and sound design are more in fashion now, and have been for the better part of the ’90s.”

When we spoke, Fisch was deep into composing two hours of music for a four-hour CBS mini series. Aftershock is about the chaos following an earthquake that hits Manhattan. Fisch was composing at his workstation, and the final score will include extensive synth and sampler parts and a 35-piece orchestra, which he will record in Seattle. Collaborating with director Mikael Salomon, whose previous work includes directing Hard Rain and being the cinematographer on Backdraft and Always, has been an enjoyable experience for Fisch. “I flew out to L.A. and spotted the film with Mikael. He has an excellent sense of timing, and I’m sure the score will turn out well. But working on movies-of-the-week and mini series is an exhausting process, with tons of music needing to be composed and recorded in a very short period of time.”

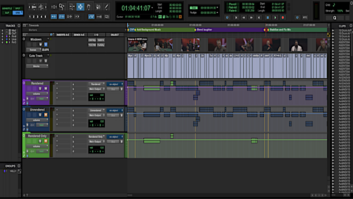

Although he’s comfortable arranging the scores he writes, Fisch sometimes finds that tight schedules require an outside arranger. He’ll be working with Larry Hochman on Aftershock (which stars Tom Skerritt, Charles Dutton, Cicely Tyson, Lisa Nicole Carson and Erika Elaniak) and is looking forward to trying out a new way of communicating. “Normally I put my ideas down on score paper in the traditional fashion and hand them off to an orchestrator,” Fisch says. “This will be the first time I’ve ever discarded paper entirely. Instead, I’ll be sending Larry Performer files exclusively.”

Once a gimmicky feature in MIDI sequencers, the notation pages in software like Mark of the Unicorn’s Performer now incorporate algorithms sophisticated enough to provide realistic playback of a performance, especially when quantization is applied carefully. “Larry will be able to play back my performances and study the score within Performer, and we’re pretty confident that he’ll have everything he needs to work with,” Fisch says.

Tascam DA-88s are the recording media of the moment for Fisch, who has a hard disk-based system that he hasn’t quite debugged yet. “I recently bought a new blue-and-white Mac G3. It has an extremely powerful engine, with a clock speed of 450 MHz, and I was led to believe that running digital video and tracking digital audio using my MOTU 2408 system would be a painless thing to set up, but for me that’s hardly been the case.

“I really don’t want to disparage any one source-there may be some user error involved as well-but the Miromotion digital video card, which is made by Pinnacle Systems, has not worked with the new G3 at all. At least not yet,” Fisch continues. “It crashes the computer, and when it does work it’s very glitchy. The audio never seems to be in sync with the video. I’ve got equipment from four different companies. As I said, Pinnacle Systems makes the video card, MOTU manufactures the 2408, Adaptec makes a SCSI accelerator card that I was told I’d need, and Adobe makes the software that runs the digital picture.

“The promise of being able to run real-time digital audio and video is very appealing, but the headaches I’ve experienced trying to get it all running have been nightmarish. Maybe a Mix reader has the magic solution to my problems! In the meantime, this is my life here, and I’m running on fumes composing this project, and so I’ve gone back to my DA-88s.” Not a bad choice, considering that the Tascam platform is still the interfacing choice for many, if not most post-production facilities.

Fisch has a system for the DA-88s that works well. “I have three DA-88s here in my personal project studio, all wired up to my Mackie 32-input, 8-bus analog board,” he explains. “I’ll drop all my synth/sampler parts to tape and head out to Seattle to record overdubs on another 16 tracks of DA-88s. We’ll replace all of my temp brass parts, but leave my string samples to be mixed in with some live playing.”

When it comes to the financial aspects of his career, Fisch finds that the composer is left to make a project work largely on his or her own. “The business of composing for television movies is simple: The composer is given a flat fee and told to do with it what he or she will. You have to balance your desire to maximize profit on the project against the importance of investing in your career. This score calls for a 75-piece orchestra; it’s a large and dramatic thriller score, in a Hollywood genre that people are used to hearing realized to perfection. However, if I hired 75 players and spent the time on a soundstage recording two hours of live music properly, the entire budget would be spent in production. Incorporating synths and samplers along with an orchestra the size we’ve contracted feels about right.”

He hadn’t finalized plans when we spoke, but Fisch intends to mix his score at Capitol Records in L.A. with engineer Rick Riccio. “He’s a heavy-hitting TV mixer, whose credits include The Simpsons, and that’s the kind of talent I want mixing this film,” Fisch says.

Fisch says that balancing a career in the jingle and television-movie worlds works out nicely: “I like the fact that jingles are relatively less pressure to work on. Plus, you’re generally working with other people, and the socialization factor is nice. Films are relentlessly taxing-16- to 18-hour days are the norm. However, this work is rewarding on a somewhat deeper level. There’s also less committee approval required; you work with the director and that’s it. As I said, going back and forth between the two is satisfying to me.”