Daniel Lanois is well-known to most Mix readers as the highlycreative, best-selling producer of landmark albums by U2, PeterGabriel, Emmylou Harris, Bob Dylan, Robbie Robertson, Willie Nelson,the Neville Brothers and others. But the low-key, easy-going FrenchCanadian native is also a formidable musical talent himself: anexceptional guitarist, songwriter and singer with three fine soloalbums: Acadie (1989), For the Beauty of Wynona (1993),and his latest, the recently released Shine. He’s seemingly gotthe best of both worlds — producer and artist — andbalancing the two lives has been an interesting juggling act. Lanois isthe first to admit that 10 years between albums is “a long time.But I’m always stockpiling music. I’ve probably got 20 albums’ worth inmy library. It’s a little difficult when I’m doing production for otherpeople: I’m pretty dedicated and don’t treat them lightly.” Rightnow, though, he’s in solo-career mode.

“After I finished U2’s last record [All That You Can’tLeave Behind], I decided that this was my time and justdevoted myself to my own music. I took writing sabbaticals in Mexico,Canada and France, and wanted to create a CD that you could listen tofrom beginning to end and not skip over certain tracks. That’s kind ofmy romantic view on records.” Lanois mentions Miles Davis’Kind of Blue and Bitches Brew as albums that meet thathigh standard. To create a similar aura, he crafted his latestrecording, Shine, around four songs that would be, as he putsit, “universally embraceable,” with the other songs beingbasically “snapshots.”

“One is called ‘San Juan,’” he continues,“and it’s this little song about getting away from urbancrossroads, finding this small Mexican village and having a romanticlife. ‘I Love You’ has dreamy psychedelic twists and someidentifiable sonic ingredients such as a repeating theme played on aLes Paul. It’s like the theme to ‘A Summer Place’ [a biginstrumental hit in 1960], and it has an exotic sound combined withthese bells I found in Mexico to create an entire vibraphone out ofthem. The instrumental ‘Matador’ is all about technology,with one note and I changed that into three with a harmonizer. Then Ibuilt them up and stored them with a bunch of different intervals.Ultimately, I played the whole thing on a keypad, not even a keyboard.Also, pedal steel guitar is a big rediscovery for me. Over the lastfive years, I found my own way of playing it in more of a gospel style.The last song on the record, ‘JJ Leaves L.A.,’ featuresit.”

In a somewhat disjointed fashion, Lanois recorded bits and pieces ofShine in a variety of locales during a long period of time. Hetransported equipment from his New Orleans studio to Tijuana and LosAngeles. Additionally, just north of Buffalo, N.Y., on the Canadianside, he maintains a “rig”, in his brother’s log cabin inthe woods. Around 1997 (he was a bit fuzzy about exact dates), he spenta number of months in Mexico, and that’s where he originally conceivedof Shine. He fondly recalls the period as “an amazingexperience” and did skeleton songs and recordings. Additionalsongs, augmentation and enhancements were done in Canada, France andfinally in his Los Angeles home/studio.

“There was basically 10 years of stuff alreadyrecorded,” remembers Adam Samuels, Lanois’ engineer, from theproducer’s home/studio located in the Silverlake area of L.A. He’s beenworking regularly with Lanois for the past three years there, and atTeatro Studios in Oxnard, where they met five years ago. At that time,Samuels was hanging out with Victor Indrizzo, a producer/drummer (Beck,Macy Gray and Drizz) and was just learning the basics of engineering.His attitude and drive impressed Lanois, and they first worked togetheron Willie Nelson’s Teatro CD (1999) at that studio. From there,he did a stint at the Sound Factory, assisting Tchad Blake for a yearbefore he relocated to England. Since then, Samuels, who’s alsoCanadian but was raised in Europe, has reunited with Lanois and ishandling his various engineering needs, including tour sound.

“What strikes me all the time about Dan is his absolutededication to innovation, uniqueness and greatness,” Samuelssays. “He doesn’t settle for anything less than amazing. He’salways fighting, even when you think, ‘I can’t go onanymore.’ He’ll have his sleeves rolled up and ready to go afterit and be thinking about how can we make this great. The song‘Tears Roll By’ came out of a loop that was made for BobDylan’s Time Out of Mind. It just had something that he felt wasgreat. But he worked at it for a long time to develop a song out ofit.”

“I did a lot of the parts on the album myself,” Lanoissays. “I find that in the heat of the moment, especially at atime when I considered a particular recording to just be a demo, I’llplay all of the instruments myself.” For accompaniment, Lanoisrecruited a few select friends: “On drums, it was mostly BrianBlade, who’s my favorite drummer. [Jim Keltner also played drums.]Chris Thomas and Darryl Johnson played bass sometimes, and Aaron Embrywas on piano. I’d wait for people to come through town, while in themeantime, I was chipping away by myself. Then I’d invite them in for afew days and see if we could shake up a little dust.”

Samuels helped turn Lanois’ living room into a studio, and much ofthe tracking for Shine took place there during the late summerof 2002. When Lanois was working alone, the pace was relaxed:Typically, recording would start around noon and end by the earlyevening. However, during sessions when other musicians were used, thesessions went to all hours. “There’s a certain aspect of thestudio that’s ongoingly mystifying to me,” Lanois comments.“You’ll tune your instruments and record on one day, and you’lltry to overdub a month later and it doesn’t quite fit in. I think themolecules are set in a certain way one afternoon and that’s the time toget the overdubs done. When ideas are flourishing and things are reallygoing well, that should never be taken for granted. That’s really agreat time to just get as much work done as you can on atrack.”

Samuels says that Lanois’ way of using equipment and laying thingsout is well-thought-out and ensures that sessions go smoothly withminimal complications. “Everything has its own job, and nothingis doing two things,” Samuels notes. “That’s a philosophyDan always tries to put in his studios. An example of that is the mainmixing console is not used for going to tape. It’s the idea ofdedication [of equipment], and luckily for Dan, he’s got enoughequipment to do that. He has a separate console for going to tape, aNeve Melbourne 12-channel with API preamps. Those are set up withdedicated microphones and sound. A channel that’s [dedicated to] thepiano microphone is always that. If you sit down at the piano, it’smiked up and I know what it’s going to sound like.”

Over the years, Lanois has amassed an impressive array of equipmentand he manages to put together similar setups wherever he ends upworking. Consoles include his vintage Neve 8068, a pair of smaller Nevedesks and an Amek. He likes Studer decks but has also found the RADARhard drive system to his liking; he started using it during U2 overdubsessions in France for their most recent CD. The RADAR was usedextensively for recording, editing and mixing tracks for Shine.“I think it’s fantastic because you don’t do data entry withit,” Samuels says. “Instead, you’re listening to music andworking with your sound, not waveform pictures and a keyboard. I preferthe sound of the RADAR, too [to other hard disk systems].” Theproducer did end up using Pro Tools, too, because his engineeringfriend Tony Mangorian brought in his setup to assist on the song“Falling at Your Feet” (which features Bono on vocals).

Lanois albums always feature unusual processing and sonics, andShine is no exception. He says he tends to use “whateverI’m most excited about,” which usually amounts to many of the oldboxes he’s had around for years, such as the Lexicon Primetime andPCM70, and the Eventide Harmonizer. He generally eschews conventionalreverb devices; for compression, he uses a Teletronix LA-2A for vocalsand a UREI 1176 for bass. Neve 1066s are his preamps of choice. Formicrophones, he’s fairly set in his ways: He says he hasn’t seen anyimprovement in the technology over the years. He listed thesetime-tested models as favorites: Sony C37A, Neumann U47 and U48, RCA 77and 44 ribbons, and the more modern Sony 800-T. He also likes dynamicmics such as the Shure Beta 57 and 58, and the Sennheiser 409 and 421.Overall, his only innovation in the mic area was using Sennheiser’sradio headphone system during the sessions, which he says,“worked very successfully.”

In many respects, gear is often secondary to Lanois; more importantis the sessions’ setting and vibe and his willingness to experiment. Heoften quotes Leo Nocentelli, guitarist of New Orleans’ famous funkmasters, The Meters: “It ain’t the axe, it’s the cat who playsit.” Samuels adds, “You can make a great record onanything. The key element I’ve learned from working with Dan is payingattention to the way things sound before the microphone. Ifyou’ve got a great-sounding guitar player and amp, then put a [Shure]57 on it. Or you read a manual that tells you how to get a great guitarsound and do whatever they say. Either way, it’ll sound good. But ifyou’ve got a guitar player on a crappy amp with bad tone, it doesn’tmatter what you do, even if you have a super-duper plug-in.”

For Lanois, recording successfully is often about the processitself, and working on so many albums has given rise to a number ofpersonal theories of what works and what doesn’t. One that separateshim from many other producers is, “I do the mixing as I goalong.” He says, “I don’t save it for a mixing date. If atrack is sounding good after an afternoon’s work, I do a mix. I findthat the best mixes often come from rough-and-ready situations, whenpeople aren’t thinking about things too much.” Samuels adds,“A lot of the mixes would be where I was toying around with ablend after a take. Dan would say from the other room, ‘That’sgreat. You got something there.’ And I would just leave it, evenif it wasn’t what I was going for. From there, he would come in and wewould both be on the console.”

Lanois likes to stay open to new ideas, and it is not at all unusualfor him to be working on several different arrangements and mixes of asong at once. “These are lessons I learned from Brian Eno a longtime ago; he’s the mastermind of unusual balances,” he says.“It’s a way of getting you out of your usual habits and maypresent you with a fresh way to look at a blend. For‘Sometimes’ [on Shine], the original version wasacoustic guitar and me. I was tempted to put that version on therecord, but I ended up with four or five different versions. I likehaving a lot of versions of songs and think you learn a lot by havinganother bash at it. Additionally, I look for sonic identities:sometimes a riff, other times a tone. A track will come on and it willjust have a sound that separates it from everything else on theradio.

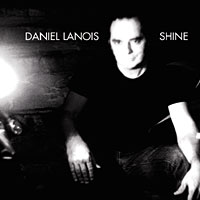

“I often wonder, what would my buddy Brian Eno think? He hadlittle involvement with this project, although I did send him the CD atthe back end for his views on sequencing. The same with Bono, and hewas very useful. While on vacation with his Dublin cronies, they wouldcall every hour as they got drunker and suggest marketing campaigns,among other things. It was a lot of fun. Bono even said, ‘You’vegot to call the record Shine [which is also the title of one ofthe songs]. Its got a lot of rain on it, but its also got a lotsun.’ Then he asked, ‘What kind of photograph are you goingto use for the cover?’ I said, ‘I’ve got a picture of me,nighttime, lit up by motorcycle headlamp.’ He said,‘Perfect, coming out of the darkness; that’s great.’ Thenhe went on to say, ‘That’s what it should be when you perform.Walk onstage back-lit and don’t let them see your face for the firstsong.’ He had it all worked out,” Lanois laughs.“He’s a very sweet man and I’m lucky to have him.”

Of course, the other side of working with the likes of Bono, Dylanand Gabriel is that beyond the camaraderie is the pressure of having toproduce under the microscope, so to speak. Amazingly, Lanois seems tothrive in those settings, yet he admits the tension level on his ownproject was more intense, especially near the end: “Those folksare all highly intelligent and creative people, and only good comes outof those situations,” he says. “That’s a wonderful arena tobe operating in, and I like the challenge of intelligence. Itallows me to get real resourceful and bring the best out of myself.There is a kind of intensity and there’s high expectations, such aswith a U2 record. Then I take those same lessons and apply them to myown productions. Yeah, maybe it’s a little more relaxed, but at theend, the same pressure exists: You’ve got to deliver.”