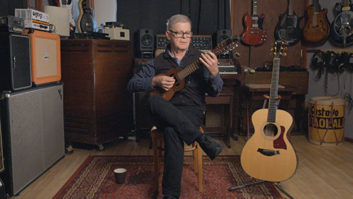

David Chesky does it all. Since 1986, he’s run his own audiophile record label, Chesky Records, which has released dozens of albums in a multitude of styles: classical reissues, new orchestral recordings, chamber music, jazz, world music, pop vocalists and more. As the label’s main producer, he has worked with the likes of McCoy Tyner, Clark Terry, Paquito D’Rivera, Peggy Lee, Phil Woods, Larry Coryell, Ron Carter, Mongo Santamaria, Marta Gomez, Badi Assad, Oregon and even The Persuasions.

A skilled pianist, Chesky has also recorded albums under his own name and with various jazz ensembles — the most recent was a marvelous recording called The Body Acoustic, released last spring, which finds Chesky in a spirited and adventurous quintet with trumpeter Randy Brecker, bassist Andy Gonzalez, conga phenom Giovanni Hidalgo and Bob Mintzer on bass clarinet. It’s one of my favorite discs of 2004. Chesky has also written and recorded many modern classical pieces, as well as genre-crossing works that merge his love of classical music and Latin jazz. It’s a wonder he ever sleeps.

Chesky is a hero in the audiophile world because of his company’s dedication to superb sonics. Eschewing conventional multitrack recording methods, Chesky prefers cutting live to stereo (and multichannel) with top-of-the-line custom equipment and variations on the Blumlein technique, using optimally placed mic pairs or a SoundField mic — whatever works with the band or ensemble. These days, he records mostly to Genex MO. He has heartily embraced 5.1 (even putting out a spectacular 5.1 demo disc called Dr. Chesky’s Magnificent, Fabulous, Absurd and Insane Musical 5.1 Surround Show) and has helped develop a different surround format, 6.0. Many Chesky releases are available as hybrid 5.1/stereo SACD releases. Chesky’s company also now markets its own high-end loudspeakers, the C-1.

Outspoken and opinionated, Chesky doesn’t pull any punches when he talks about the audio and record businesses.

The Chesky approach is to record live with a single mic array. How did you arrive at that methodology?

Mostly from just what sounds best to me. I’ve been involved with music my whole life, been in all sorts of different kinds of groups since I was really young. I’ve also been a classical composer and conductor. Anyway, when I used to conduct for television and movies, I would stand in front of an orchestra and it would sound great. I was a kid then, 19 or 20 years old. They’d have 20, 30 microphones set up and then we’d go back to mix it and it would always sound weird to me because the engineers would essentially be putting the orchestra back together. That stuck with me, and when I started my own label later, I wanted the sound to be from a single point and not all divided to be reassembled later. That’s why we started doing M/S recording. The multitrack is cool for certain things, but our philosophy is trying to document the live event and we do it with a stereo microphone. We set the musicians up very carefully and the electronics are minimal, but we’re using the best-sounding equipment we can. When you hear our stuff, it’s super-clear — everything is the best wire, the best amplifier, the best mic pre.

And it’s all custom gear.

Most of it. We build some things, but we also use some off-the-rack stuff, like our A-to-D [converter]. It’s a commercial one that we rebuilt. I’m not going to mention the name because one of them blew up on me last night. [Laughs]

What’s your current mixer?

We built it; it’s an 8-channel tube mixer designed by George Kaye [of Moscode Inc.]. He also did some work for us on some OTL [amplifiers] and things like that. We’ve modified microphones and we also do SoundField [MkV] miking.

You’re also a strong advocate for surround.

We’ve been pioneering an experimental format called 6.0. When you think about it, 5.1 is basically glorified quad. In 6.0, we have two height channels on the side at 55 degrees. I’m not that interested in stereo recording. I’m much more interested in making three-dimensional recordings. We’re into enveloping. If you come to my studio and listen back to a surround in 6-channel, it’s like you’re at the event. When you listen to a band in stereo live, the audience is in the 2-channel field. Now with the SoundField recordings, the band is in front of you and the audience is to the side and in back of you. We completely envelop you, which 5.1 can’t quite do, though we also matrix it for 5.1 for commercial releases. But this could be a future format. We were the first people to record at 24/96, we did the first oversampling chips, all that kind of stuff.

How would you mike a large band in 6.0?

With a single-point SoundField or an M/S with an omni. We could matrix it to 5.1 or 210 channels; it doesn’t matter.

How do you monitor that?

It’s really hard to monitor, because with the types of places we record — churches and such — you’re pretty much monitoring in the coat-check closet. [Laughs] We monitor a lot with headphones.

If it was a live concert from Carnegie Hall, I could put you in the fourth row, like a holograph. That’s going to be the future of mixing. Let’s not think of stereo or quad — let’s think of a three-dimensional space like you hear in real life.

Even with all the hype, so few people have adequate playback systems for surround. The numbers are still so small.

They are small, but look, you’ve got to start somewhere. We might be 10 years ahead of the curve and never make any money from this, but that’s not the point. Part of it is the art of the thing. If I were into the bread, obviously I wouldn’t be doing this. But this is our thing. We’re like the little French restaurant and the other companies are McDonald’s. We have our loyal audience. We’re doing okay. We want to make the best product we can; for people with high-resolution systems, these are the best recordings they can find. Then again, there are also a lot of college kids who are buying The Body Acoustic and playing it on boom boxes and computer speakers, and they’re digging it, too.

I find there’s a dichotomy in the recording world because you have this split. People want the technology to really advance the state of recording, but at the same time, most kids now listen to records on $10 plastic computer speakers. The ability to listen attentively seems to be getting lost. When we were growing up, you went home and you really listened to those records, whether it was Beethoven or the Grateful Dead. You put that needle down and it took you somewhere. It’s what we came to expect from music.

I don’t care if you’re an audiophile or not, but if you’re in a rock ‘n’ roll band and you spend nine months in a studio, you don’t want people to listen to it on computer speakers.

Do people who buy your jazz records also buy your classical recordings because they’re audiophiles?

There are some who like only our jazz or only our classical or only our world music, but there are some who just love the way our records sound. My label is an adult-oriented label. It’s acoustic music with real musicians. We don’t do overdubbing; you don’t go into the studio for nine months. We find the best pianists, the best jazz guys, the best orchestras and we go in and record them.

Surely you do editing.

We do editing. If there’s a wrong note, we take it out, but we don’t do overdubs and punching in.

How do you take out a single note from a stereo SoundField recording?

I have a guy named Nick Prout who’s brilliant on the Sonic [Solutions system]; he can take out a 32nd note. What we do is record two or three takes. Chances are, nobody is going to make the same mistake twice. We’ll edit between performances as necessary. For this kind of recording to work, you need great musicians, a great engineer and great editors. I’m really happy I have a staff of people who will do what needs to be done and do it right. I know if I give the tapes to the editor, he’s going to go through it better than I ever would. It’s so important to have a good team. It’s not about me. I’m like the coach.

Who are the people who influenced you sonically?

Well, I started my label by reissuing the classic [Charles] Gerhardt/[Kenneth] Wilkinson records — Reader’s Digest records by some of the guys who invented the Decca Tree! The first record I reissued was the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2 [in C minor, Op. 18], and that was it. We did reissues for two years and then we started making our own records when we had the money, using some of those techniques but with our own [improvements].

When stereo records started happening in the ’50s, the people who owned the labels were passionate about it. The guys who owned record companies were into the music; they weren’t bean counters working for multinational corporations. Even the big guys at the labels were musicians. The engineers were real engineers — they could build mic pre’s and build amps and they really understood the equipment they used. It was a different head. People had Marantz and McIntosh [amps]. Really, it was an audiophile era by default.

My aesthetic is to create a real event with dynamics. Unfortunately, we live in a world that doesn’t want dynamics. On the average pop record, the object is to get the needle not to move. We’re teaching the population of the world that dynamics are bad. So you have two opposing factions — one is saying let’s do a great thing and have high-resolution multichannel audio, and the other is saying let’s make things that sound good compressed on the radio and on MP3s through computer speakers. The sad thing is, when you go to an AES show, you have the smartest people in audio up there giving papers and demonstrating high-end equipment, when in reality, the industry is geared to some fictitious 14-year-old girl who lives in the Midwest who is downloading compressed files to her iPod. Imagine if everyone tried to make things great instead of dumbing everything down. We have the technology right now to create affordable home theater systems that will truly put people in another space and hear things in ways they never have before.

How did you transition from being mainly a musician to mainly a producer?

I had been writing and arranging and playing in studios my whole life — classical and jazz. And being an arranger, you’re pretty much already producing. You’re writing the charts and working with the engineer because you know what it’s supposed to sound like. After a certain point, I said to my brother [Norman, who helps run the label], “Instead of waiting for the phone to ring, let’s be the catalyst and make the records we want to make.”

Was it hard to get the word out? Marketing is so hard.

Marketing is tough, especially for a small company. But we always had good word-of-mouth from the beginning and that goes a long way in the jazz and classical worlds. We always felt encouraged about what we were doing.

I don’t have the resources that Sony and Warner Bros. have. Fortunately, over 18 years, we’ve built a big audience around the world where our logo actually means something. We’re never going to be about making hit records. We’re into making great records.

When you work with someone like McCoy Tyner, does he know there’s going to be a certain approach to the recording that might suggest a certain kind of repertoire?

Everyone knows how we record. We’re going to be live in a room and we’re going for dynamics. So I’ll tell the drummer, “If you play too loud and you can’t hear the piano player, there’s nothing I can do. You’re a musician and you have to learn how to play with dynamics.” That’s how they used to do it. The problem is, musicians and engineers have relied on using all these microphones and tracks as a crutch.

Are there some instruments that lend themselves more to the kind of recording you like to do than others? Like when you did The Body Acoustic, you’ve got piano and a muted horn and Giovanni Hidalgo banging away on the congas. Are there certain overtones and subtleties in some of the instruments that are picked up more easily in the type of miking you like to do?

Pianos are hard sometimes because the [dynamic] range is so big. And that’s my instrument, so I’m very sensitive to it. Really, though, a lot of it is getting the musicians to play with each other in a way that is sympathetic with the acoustic space we’re recording in. Like Giovanni is used to playing with these big Latin bands and whacking those congas. He’s amazing; he’s like the Heifetz of the congas. In his world, he’s as good as anyone on the planet.

[The Body Acoustic] was tough for the reasons you said. It’s an interesting combination of instruments and textures. But the engineer [Barry Wolifson] did a great job. I’m really happy with how it turned out, and we’ve gotten a really good response to it.

What are your favorite spaces to record in?

I love churches. I love concert halls. I love jazz clubs. The space is so important. If you’re in the wrong place, the best mics and mic pre’s aren’t going to save you. We record all over. Everything is in racks on wheels.

Are there other producers you admire?

I really love the work of Reference Recordings. Tam Henderson and Keith Johnson are brilliant. They’ve done such wonderful stuff. I also really like Tom Jung’s work. A lot of the best stuff is coming out of small labels. They have passion.

I know you’ve gotten to produce some of your heroes. Can you be a fan and a producer?

Sure, but it’s true that once you produce someone, that changes the relationship you have with that artist, and I don’t mean that in a bad way. You can’t be sitting around just admiring them and thinking how great they are. [Laughs] Suddenly, you’re in a position of power and you’re helping them achieve something; you’re working as an equal in some ways. If there are mistakes, you have to get them to do it again. You’ve got to be able to say, “Hey man, in bar 24, that note is wrong, it’s flat.” I idolized people like John Lewis and Clark Terry when I was a kid and then here I was, 20 years later, telling them what sounds good. It’s wild, but it also felt natural to me.

We’ve read all these stories about the dire state of mainstream jazz and classical recordings. Sales are down across the board; people are struggling. Do you exist outside of that business because of your audiophile credibility?

That’s definitely something we have going for us — the audiophile thing. But it affects us, too. We talk a great game in this country, but at the end of the day, we do absolutely nothing to educate kids about music. You go to Italy and every truck driver, whether he listens to Puccini and Verdi or not, respects them. Every young kid in the United States should know who Coltrane, Ellington and Parker are. If they’re not into it, fine, but they should at least be exposed to it and respect the art form. Unfortunately, we live in a time where everything is disposable and there’s no respect for these people that laid the groundwork. It’s sad. As long as politicians pay lip service to helping schools but in actuality cut arts funding, they’re going to get the culture they deserve.

American Idol, MTV…

Right. American Idol. McDonald’s. Kids aren’t out there saying, “You know what? I want to hear the Mahler 8th.” They’ll never hear it unless they search it out or someone plays it for them. Same with Coltrane. Same with most music outside of the mainstream. A lot of kids don’t even know where to look. There’s so much more out there. It’s like farming: You have to plant the seeds for the next generation.

For more on Chesky Records and Chesky Audio, visit

www.chesky.com.