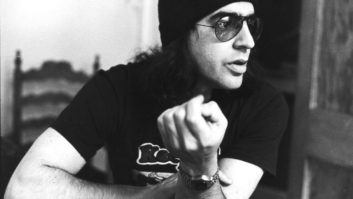

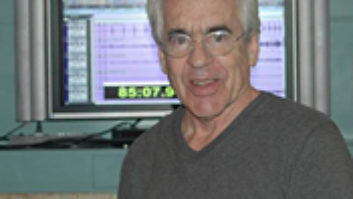

Elliot Mazer has had a long, varied and distinguished career as a record producer, studio owner/engineer, entertainment technology company executive and audio consultant. Primarily known for his 30-year association with Neil Young, Mazer has also produced hit albums by Linda Ronstadt and Janis Joplin, worked on The Band’s The Last Waltz film and album, and developed the AirCheck monitoring system, which automates the recovery of publishers’ royalties from radio stations.

Most recently, Mazer has been working with Neil Young on a DVD-Audio reissue of Harvest, Young’s chart-topping album from 1971. For Mazer’s description of the recording of “Heart of Gold,” the Number One single from Harvest, see Classic Tracks on page 198.

I understand that you are mixing the Harvest DVD-A at Neil Young’s Redwood Digital studio. Can you describe the technical setup?

I thought that it would be important for Neil to have a dedicated 5.1 monitoring system in his control room that is reflective of what a consumer would have at home. He has a 5.1 soffit-mounted TAD system that works well for tracking and film mixing, but that’s not really representative of current consumer 5.1 systems. Craig Street, a wonderful producer and longtime friend, talked to me about the stereo monitoring system that he carries between studios. He came over to my house and played a few of his projects on my new Parasound/Energy system. Craig concluded that my system properly reflected the subtle decisions he had made on his bigger system. Neil purchased a six-speaker system with Studio 100 speakers and associated power amps. This worked well, and the mixes we made sound good on other systems.

DVD-A has amazing potential. It enables the public to enjoy high-resolution recordings on relatively inexpensive consumer products. I am convinced that we will be able to buy complete DVD-A systems — with six speakers — for under $500 by Christmas 2001. Right now, the price point is around $650 for the complete system I use, which is a Technics A-10 and a Creative Labs Desk Top Theater 5.1 speaker system that cost me $139.95. I used it in my hotel room to review new mixes every night. It was very helpful.

Setting up Neil’s studio for a 5.1 mix was interesting. We set up both digital and analog recording systems, using Genex MOD recorders for digital storage and an analog Studer 827 2-inch 8-track. We transferred the original masters to digital through PMI HDCD Model 2 boxes at 192kHz, 24-bit; the sound of 192/24 is amazing and very different from 96/24.

How is Neil’s attitude toward digital these days? He made an impassioned speech on fidelity and “bad” digital at the TEC Awards event a few years ago.

John Nowland, Neil’s studio manager — and a wonderful Bay Area engineer who did projects at His Master Wheels [Mazer’s San Francisco studio] and ran Merle Haggard’s studio — did a 192kHz, 24-bit transfer of the Harvest stereo master through PMI converters. I played a DVD-A of that for Neil in his control room, and he, like all of us, was amazed at how real it sounded. It sounded like analog. Neil has spent a considerable amount of time and money on digital gear. He wants it to work, and I think he is happy now. Neil is transferring his analog library of music through the PMI Model 2 HDCD boxes at either 176.4/24 or 192/24. He is spending his own money on this project, and that is a serious level of commitment to digital. I believe Neil makes his new recordings on 16-track 2-inch 30 ips. He uses SMPTE to lock together the necessary machines.

For the DVD-A remix, we had to overcome some technical and practical issues. Recording six channels of 96/24 uses lots of disk space. Neil has been using Genex MOD recorders at his studio, Redwood Digital, for years. The current Model 8500 is in Beta release, so far as I know, and has its share of problems. We were getting a huge number of errors during takes while writing to the MOD disks. Denny Purcell of Georgetown Masters gave us a bunch of workarounds for these problems. One was to never put more than 13 minutes of music on a disk per side, and the other was to only use certified disks. We tried both and still had problems. We came up with a system that worked, but we incurred unnecessary costs and spent a lot of extra time.

Here’s how it worked: During the DVD-A mix sessions, we only wrote to the internal hard disk, and when we had 13 minutes on the hard disk, we made a SCSI backup to a MOD. After we listened to the SCSI backup, we made a second MOD SCSI backup. The SCSI backups have to be done in real time, as does the listening. So 13 minutes of security cost us 3× 13 minutes for listening and 2× 13 minutes for SCSI copying, so 13 minutes of music took us 75 minutes to check. We did get perfect copies, but we wasted 20 percent of the disks and a lot of time. I know that you can argue that we would have to make the copies anyway and listen to them, but you cannot selectively backup files from the Genex hard disk to MOD. I needed the hard disk for my next mix, and I wanted both MODs to be made from the original hard disk master. This made it necessary to do this during the mixing sessions, which was disruptive and costly.

A second problem we came across is that to get these bits into a DAW, you have to make a real-time AES transfer. Some of the DAWs don’t sound great at high bit rates, and one has to be careful about degradation. It would be much better if Genex, Sonic Solutions, Pro Tools and other manufacturers all complied with AES 31 and enabled us to move files around.

How practical was it to use Young’s Neve 8078 for mixing for 5.1?

The audio quality of the 8078 is amazing and therefore worth the effort to make it work for DVD-A. It’s obviously a vintage console, but Neil has spent a lot of money getting it in shape, getting it back to original specifications, and it is so versatile that it is not much of a chore to make it work for 5.1. The monitoring section was obviously not 5.1-ready, so Neil had some third-party gear installed to handle 5.1 switching, level matching, etc., but this gear deteriorates the audio quality in the monitoring chain. I hope that a manufacturer comes along with a high-fidelity 5.1 monitoring system that can be used on consoles built for stereo or quad.

Our signal chain was simple. The front two channels and surround channels we sent through two pairs of buses, and used Rev Send 3 for the center channel and Rev Send 4 for the subwoofer (LFE) send. Deciding what goes to the subwoofer is one of the trickiest aspects of mixing 5.1. If you rely on the subwoofer for most of your low-frequency information, your final mix will be bass-light on systems that do not have subwoofers, so I turn the subwoofer off when I am doing my basic mix. When this mix starts to sound like music, I turn on the subwoofer and blend in an appropriate amount from various instruments.

The buses fed three Model Two HDCD converters and the 2-inch 8-track Studer. On some songs, I preprocessed the mix through the Studer before it reached the HDCD box, so some of the songs on the Harvest DVD-A have been run through the Studer Record/Play chain, and some were sent right into the HDCD boxes. Plus, Neil has an analog backup of all the 5.1 mixes on the 2-inch 8-track. The audio quality of the analog backup is amazing.

You mentioned that you had a portable 5.1 system, but surely you used something a bit more sophisticated for checking your mixes at home?

I have a bunch of playback systems at home. The main system consists of two Ed Long speaker systems, each one larger than me! They are fed by a pair of McIntosh tube amps and a Parasound P/LD 1100 preamp designed by Bay Area audio legend John Curl. The CD player is a Rotel RCD 971 HDCD player. I also have a wonderful turntable and assorted DAT machines.

When we started to talk about the Harvest DVD-A project, I decided that I needed a 5.1 system. I went to Parasound and found an HCA 2205 5-channel power amp designed by Curl and a multichannel preamp/processor that did Dolby Digital, DTS, TMX and high-resolution analog (AVC 2500). The Energy xl16B speakers are a little bigger than NS-10s, and I have an 8-inch powered subwoofer. The DVD-A machine is the Technics A-10, which has analog outputs for 5.1. I set up the speakers at home and at Neil’s studio using a formula designed by Georgetown Masters, the mastering studio we are using for Harvest. This was tricky, but in the end I could hear well from most places within the speakers. I can’t presume that most people will set up six speakers perfectly and always sit in the middle — most people cannot set up two speakers correctly. Engineers, headphone users and people that listen on their PCs are among the only people that sit in the “correct” place to listen. If the music changes substantially when you move around or when the six speakers are not set up properly, there is something wrong with the mix.

You grew up in New York City and suburban New Jersey and went to college there. How did you get into the industry?

I loved music as a kid. Jazz and folk were my passions growing up until Elvis landed. I loved looking at and listening to records and got a job in the Sam Goody record store while I was going to college. One of my jobs was singles buyer for the store, and one day the Decca salesman came in and played me “My Generation” by The Who. I loved it and ordered five copies for the store, even though it was not on radio and nobody had heard of them in 1965. I played the record in the store, and people bought it. That really got me excited. Eventually, I got to know Bob Weinstock, the founder of Prestige Records. He asked me what I wanted to do, and I told him that I wanted to make records. He hired me, and I went to work for him doing all kinds of stuff like delivering DJ copies to stations, sorting the tape library, listening to new releases, checking label copy. He let me visit the studio and watch the recording process.

Esmond Edwards was the A&R guy, and they used Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, N.J. Esmond was making records with Red Garland, Oliver Nelson, and the studio was, and still is, fantastic. Rudy had a tube board with rotary pots, similar to what Columbia had at their studios, and he had mono and stereo Ampex 300s and perhaps a 3-track ½-inch 300. Rudy got the sounds, the A&R guys worked with the musicians and the stuff sounded great. The room is beautiful and very lively. Rudy recorded big bands as well as small groups. This was live recording — you put down exactly what the consumer would hear. My first production was a bossa nova album with Dave Pike. Clark Terry played trumpet, and I produced two of Clark’s albums a few years later for Cameo.

Skipping ahead to the ’70s, you produced albums for American artists such as Neil Young, Janis Joplin and Linda Ronstadt, but you also went to England to record Frankie Miller, Rab Noakes, Mike D’Abo and Andy Fairweather-Lowe. How was life as a continent-hopping freelance producer back then, and how have things changed?

The ’60s and ’70s were wonderful times for recording. You could really hear where a recording was made. Memphis sounded like Memphis, L.A. like L.A. and London sounded like nothing we had ever heard. The British studios, musicians and producers had a completely different rulebook and completely different kinds of equipment and tastes in music. American engineers, for the most part, used rooms and miking technique in an attempt to translate a literal copy of an instrument onto tape. British engineers used EQ and whatever gear they could find to create a sound, which did not necessarily have to be a literal copy. U.S.-made consoles had EQ with ±12 dB, while British desks had ±20 dB. A British studio setup would have a zillion U67s, while an American setup would have a bunch of different mics. The British producers, engineers and musicians loved the music coming out of Memphis and Florence, Alabama and Detroit. Americans wanted to sound like The Beatles, who really started out wanting to sound like the Everly Brothers or Chuck Berry, etc.

Early UK studios, pre-Neve and pre-Trident, had very simple equipment. Most desks had little or no EQ, and most control rooms had one or two compressors, if any. Reverb came from live chambers. Glyn Johns told a story recently about the desk at Olympic, which had one EQ knob and only two settings — pop or classical. Glyn, like most engineers and producers who started in the ’60s, learned to get his sounds from the musicians. People ask him which compressor he used on the bass drum on “Honky Tonk Women.” I get asked which one I used on “Heart of Gold.” The answer to both those questions is none. We worked with great drummers who knew how to make their kits sound great, and we know how to capture those sounds and put them in perspective. Those were literal sounds. George Martin used whatever voodoo was appropriate to get sounds on Beatles records. They were not necessarily literal sounds.

During the ’70s, things started to even out between the U.S. and England. Neve desks were coming to the U.S., and many of us were working on both continents. Brits made records here, we made records there, and, by the end of the ’70s, records started to sound the same — too bad. Then MTV came along and really clinched it. Everybody could see and hear everybody else’s music. The labels wanted the artists and producers to make hits that sounded like the current hits, and individuality started to overtake creativity. It was no longer the case that a record made in a specific city sounded like that city.

Today, Pro Tools and other technologies level this playing field even more. It is now possible to make complex-sounding records anyplace, and for a fraction of the cost of years ago. But the essential thing about a great record is the quality of the song and what emotion is transferred to the listener.

The two records you made with Area Code 615 were recently re-released on CD by Koch. They were very influential at the time, and I was surprised that it took so long for them to be re-released.

We had to go through a huge amount of red tape to get the CD out. The reissue happened in 2000, 30 years after we cut the records, and Universal could not find the contracts. It turned out that Mac Gayden had them, and we sent a copy to Andy McKaie at UMG. He got us back into the system, and Koch made a deal with them. UMG had the original ¼-inch master for the first album, but Polygram had lost the master for the second LP — we had to use a Dolby A tape dupe master and a Dolby A 8-track copy.

The Area Code 615 records were cut at Cinderella Sound, which is a two-car garage behind Wayne Moss’ house in Madison, Tenn. Wayne, a top session player in Nashville, had converted his garage by building a control room and adding acoustical treatment to isolate and shape the sounds. It had a drum booth built by Wayne and Kenny Buttrey, legendary drummer for the Everly Brothers, Neil Young, Bob Dylan, Elvis, George Harrison, Simon & Garfunkel, etc.. Wayne, Kenny, guitarist/songwriter Mac Gayden (who wrote “Everlasting Love” and played with J.J. Cale and Bob Dylan) and harmonica virtuoso Charlie McCoy (George Jones, Bob Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel) had a band called Charlie McCoy & The Escorts. They were mostly an R&B band, and the 615 project was conceived to have R&B rhythms under country sounds.

You also worked with The Band on The Last Waltz.

From the start of TLW, it was obvious that none of us would settle for anything except perfection. We would have one show, one night to document the music of The Band and their friends. We spent months preparing for this gig. Robbie Robertson, Marty Scorsese, The Band, Bill Graham and his people met many times to plan this massive event. Marty wrote a shooting script that was from The Band’s lyrics. The seven cameras and my truck got their cues from these pages. We rented Wally Heider’s truck, which had a large API console, two 3M 24-tracks and racks of Dolby A units. We recorded at 15 ips, Dolby A, with sync on track 24. I used my Neve Melbourne 12×2 desk for additional inputs. The truck split many of the P.A. mics, and we added extra mics for piano and drums. I did not use any compression, and I had to hand-ride everything. I had to anticipate every move onstage.

We rehearsed for two days. Every song was rehearsed, and most of the guest artists did onstage rehearsals. Muddy Waters and Bob Dylan did private rehearsals at the Miyako Hotel. Ray Thompson, one of the great remote recording engineers, came up to help me mike the show during the rehearsals. Ray knew how to make live sound live — Frampton Comes Alive and Aretha Franklin Live at the Fillmore West are part of his repertoire. Ray worked mostly on the house mics and the piano.

The gig was amazing. There was one place in the show where all of us had a problem. When Paul Butterfield came onstage, Robbie broke a string, Paul went to the wrong vocal mic, a lighting panel went down and half the cameras ran out of film during the delay. It took all of us a few minutes to recover, and then everything was fine throughout the show. There was a problem with the AC power feed to the truck, and some hum got on tape as a result.

The post-production for the film and record were done at The Band’s studio in Malibu, Shangri-La. I was not involved in this process, as I was too busy in the studio. I like the way the movie sounds and hope I get to hear a great-sounding DVD-A out of the music.

Tell us more about the Jack Nitzsche album.

That project was recorded in St. Giles Cripplegate, a first-century Church of England gothic church in the Barbican area of East London. The timpani were literally placed over the grave of poet John Milton. Bob Auger set up his Neve rig in the rectory office, which is next to the pulpit. The pews were removed, and the London Symphony Orchestra was set up in the traditional way. (David Meacham, the conductor, had previously conducted the LSO on the two songs they recorded with Neil Young on Harvest.) Bob Auger knew the hall and the orchestra.

We recorded to 8- and 4-track machines at 30 ips. The speakers were Tannoys. Jack sat mostly on the lounge chair between the speakers listening. David Meacham would ring the intercom and ask me if in measures 134 to 140 the first violins were to play F, F-sharp, G, G-sharp, etc. I would look at the score and see if that was what Jack had written and then ask Jack if this was okay. It was correct, and, for the most part, we just had them make one or two takes. The sessions took two days, and all went exceedingly well. I did the stereo mix at Quadrafonic. I wound up using just the monitor section of the console, since the mix was really a re-balance and no processing of any type was needed. We hope to do a DVD-A version of this album soon.

How did you get involved with the Jazz Masterpiece reissue program for Columbia Records?

A friend at Columbia Records (Jack Rovner, now president of RCA) asked me about my association with Windham Hill — I had produced a few projects for them, including a Michael Hedges album — because Columbia felt that they did not know how to market to the “new age” consumer. I told them that I thought that this market would love many of the albums that Columbia had in their catalog. They asked me to make up a list of potential releases, and I did. This was the start of their Jazz Masterpiece Series. I suggested that Erroll Garner’s Concert By the Sea was the prototype new age album, as were many Dave Brubeck, Billie Holiday and Miles Davis records. They were jazz records that spoke to a mass audience. Along with Concert By the Sea, I targeted albums such as Kind Of Blue and Take Five. Larry Keyes, a Columbia engineer who I had worked with on Janis Joplin projects, did the transfers.

Can you explain your association with CCRMA and “the world’s first all-digital recording studio”?

One of the engineers at His Master’s Wheels kept telling me about the musicians at Stanford who were using computers to create and modify music. Eventually I visited CCRMA [Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics] and was truly amazed. They were in the DC Power Lab at Stanford, which they shared with the Artificial Intelligence group. They were using PDP 11 computers to do synthesis and digital processing. The machines were the size of large New York apartments, and they had 64 MB of RAM and huge external hard disk packs that stored something like 300 MB. This was in 1977. Andy Moorer, the inventor of Sonic Solutions, John Grey, a musician with a Ph.D. in psychoacoustics, and Loren Rush, a well-known composer, were the core of CCRMA under the leadership of John Chowning, the inventor of FM synthesis. They had primitive AD/DA boxes.

CCRMA amazed me. I saw music being composed, arranged, processed, morphed, created and stored in boxes. I heard the box do things to analog sounds that could never be done in the analog world. Check out our CD on Elektra, The Digital Domain. This project was created mostly in the box. It consists of analog sounds, fully digital sounds, synthesized sounds, and it was recorded in the early 1980s. Andy Moorer created a piece called “The Lions Are Growing” — the first time I had heard morphing. A human voice becomes various instruments.

I was their analog person, and I showed them how we made records in the analog world. I got to play with their stuff and very much enjoyed being around some really smart people. Julius Smith, another CCRMA guy and a fine musician with a band, later did the audio stuff for nEXt. I think Julius is still at the lab. Mickey Hart and John Meyer spent time there. We showed CCRMA stuff to Ampex, the leader of the analog world, Wally Heider, Glen Glenn, Neil Young and many others. Those that saw the system were amazed, although it took a few years for the software and hardware to become universal and accessible to the masses. CCRMA bred the Yamaha DX7 synth, Sonic Solutions, nEXt and Apple audio, Liquid Audio and many other companies and many recordings.

As an early proponent/developer of digital recording technology, are you surprised or disappointed by the current state of the recording industry? Has Pro Tools been a positive force in the industry?

I think that Pro Tools and MIDI and samplers are wonderful enabling tools. These tools have created a new way of making music. The song and the performance are the essence of a record. What is recorded is much more important than how it is recorded. It is music. I am sure we will see great products such as Pro Tools, SampleCell and Vision working at 192 kHz/24-bit. When this happens, these tools will let us create recordings that sound analog, and, to me, that is a good thing.

What is the AirCheck monitoring system and how did that evolve?

AirCheck is passive broadcast monitoring technology that I started in San Francisco in the early ’80s. This system listens to the radio, the Internet and watches TV. It identifies what it hears — it is very intelligent software. The idea for this technology came from meetings I had with a friend who was a marketing guru at Columbia Records, Jon Birge, who told me that nobody really knew what was on the radio. I spoke to my friends at CCRMA, and we started to come up with an idea of how a computer could do this.

Neil and I were working on Everybody’s Rockin’. We heard a story about a DJ who suddenly made a lot of money at the tables in Lake Tahoe. This guy had convinced a label that he was playing their record. The joke was, he wasn’t and he was getting paid anyway — listen to “Payola Blues” on Everybody’s Rockin’. Cut to a few years later, and we find that the labels know what is on the radio, because AirCheck and BDS tell them. I sold my company to Radio Computing Services in 1989. AirCheck is being used to monitor radio in the U.S., France, Holland and Brazil, and monitors TV in Germany and Brazil. RCS is the leading supplier of technology to the radio industry, and I am happy to be a part of it.

Is it too early to say whether the launch of DVD-A is a success or a failure? What might have been done differently?

The DVD-A machines that I have played with sound great and are fun to use. The system has great potential. It is too soon to know much about all this, but I am very optimistic. Warners have put a huge amount of effort into this project, and I am happy about that. Wait ’til people hear 192/24 on a consumer player that they can buy for $500!

Chris Michie is a Mix technical editor.