In recent years, Jim Abbiss has stepped into the limelight as the producer of a string of hit records by mainly young and trendy British bands. Most notably, he produced Arctic Monkeys’ Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not — a phenomenon in the UK, where it was the fastest-selling debut in album chart history; it also reached the upper regions of the U.S. charts.

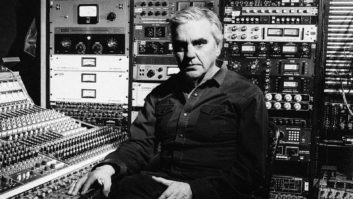

Photo: Paul Tingen

Whatever People Say was nominated as Best Album of 2006 for the prestigious Mercury Music Prize (Britain’s equivalent to the Grammy Awards), as was another Abbiss production, Editors’ Back Room (2005, a UK Number 2 album). He also co-produced Ladytron’s Witching Hour (2005) and Kasabian’s eponymously titled debut album (2004), and he had production input into recordings for Placebo, Suede, Lamb, UNKLE, Clearlake, Goldfrapp and more. In addition, he co-produced Kasabian’s latest album, Empire, with the band.

This impressive track record must put Abbiss at the top of many a young bands’ “to call” lists, but strangely, very little is known about the man. Google his name, and all that turns up are some credit lists and a few name-checks by bands he’s produced. One of the reasons for the lack of information is that Abbiss has done hardly any interviews. This is, he says, speaking in the mix suite at Olympic Studios in West London, “because I consider what I do in the studio as the background to what the artists are doing. It’s not about putting my stamp on records.”

With very little to go on, journalists have categorized Abbiss with tags like “electronic rock producer” and “indie rock producer” because electronics and heavy, jangly, electric guitars are featured on many of his productions. The producer balks at such portrayals, however, effectively arguing the title of that latest Arctic Monkeys album. “I hate being pigeonholed. Having said that, I do like working with young bands,” he says, “because it takes me back to the excitement of when I was 14 and played in a band.”

As a teenager in the early 1980s, Abbiss not only played in guitar bands, he also got involved in electronics and built a drum machine. The young man felt inspired by the D.I.Y. approach of the latter days of punk and “the original indie music explosion in the UK and early electro from the U.S.” Finding that he didn’t excel as a musician, Abbiss started work as an assistant engineer at Spaceward Studios in Cambridge and then moved to the Power Plant in London, where he ran the common gauntlet of teaboy, tape op and assistant engineer before becoming chief engineer at Maison Rouge.

When Maison Rouge closed in 1990, Abbiss went freelance and built up an impressive resume with engineering and remix credits for the likes of Björk, Massive Attack, The Verve, Sneaker Pimps, System 7, David Gray and many others. Yet by the end of the 1990s, Abbiss had that sinking feeling of his day job turning into drudgery. The way he handled this occupational crisis laid the foundation for his current successes as a producer.

It sounds like a major shift happened for you in the late 1990s.

Yes. I found myself doing endless sessions, some of which I didn’t always want to do and some I don’t even remember anymore. So I took a couple of years off to write music, after which I came back to working in studios refreshed and looking for bands that I really wanted to work with and be more creative with.

Recording is supposed to be a creative process, yet I had worked on so many projects in which people treated recording as a series of jobs. They would put up wall charts, and it would be drums for three days and then bass for three days and so on. I’d also had four programming rooms over the years, in which I did my own writing and a lot of dance music. That method is now taken even further, with people recording drums in a studio and then going into a small programming room in an industrial estate to do all their programming. I don’t think anyone really enjoys that process. I got bored staring at a box. I realized that I was happiest in a studio with lots of equipment and being able to go wherever the mood takes you and the band. The best use of my brain is not looking at a computer screen; it’s getting musicians to play together.

Can you give some examples of how your working methods changed after taking two years off?

I returned to work by taking part in the making of UNKLE’s Psyence Fiction, which was a watershed for me. It was a fascinating project, and I found DJ Shadow [bandmember with James Lavelle] inspirational to work with. His attention to detail was incredible. He did not know any technical terms or how the desk worked, so he would ask for sounds that gave him a feeling. He’d say things like, “When it comes to the middle section, it should have the feeling of an airplane coming over and nearly deafening you.” The way he approached music made me completely rethink the way I did sound. After that, the desk became a much more creative tool again.

Also, I try to make recording as much like a performance as possible. I like to have the recording room set up for the whole band for the whole time we’re recording. If at any point someone goes, “I’m not happy with the way we did so-and-so,” they can go and play it again. All we need to do is begin a new session in Pro Tools and have another go. But if you have invested a lot of time in organizing things with wall charts and so on, you don’t want to go back and redo things because it’s such a pain to do. So I don’t use wall charts. This means that you don’t have the drummer bored shitless after the first week because he’s got nothing to do anymore.

I always try to get a song to the stage where all main parts are recorded, including the vocal, before moving on to the next song. All the details may not be there yet, but when you put the song back on a couple of weeks later, it makes sense as a song. Of course, I do make notes, and when we feel that we need an additional part or something, I’ll make a note of it. But I take fewer notes now than I have ever done, because when you put a track up again after you’ve had a couple of weeks break from it and everybody is there to listen to it, it will be evident to everyone if it needs something.

Finally, everyone can buy a computer and loads of plug-ins now, and that’s great. I’m all for the D.I.Y. approach. But the result of everyone using the same equipment and the same presets is that many records sound the same. With the D.I.Y. approach in the past, people had many different collections of equipment, and they had to get the best out of what they had. They had to push what they had to its limits, whereas now, you can buy a plug-in or effects bank with classic sounds and it all kind of blands out. That doesn’t interest me. What interests me is equipment that has been built with great care and has great character. I’ll always prefer a dedicated hardware box over a plug-in.

The Arctic Monkeys’ Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not was recorded at The Chapel Studio near Sheffield over a period of 15 days with you and Ewan Davies engineering. Can you tell us the story of the making of that album?

I didn’t do pre-production with the band because I didn’t need to. There was only one song that needed to be re-thought, “Riot Van,” because they had changed quite a bit of the lyrical content and structure, and they were not sure how to go about finishing it. But the rest of the songs were very well worked out, so it really was a case of them setting up and playing the songs through. They had done a lot of touring and were playing things very fast, so I generally tried to get them to play a bit slower so you could hear the words.

I had the whole band in one room, with the two guitar amps in a booth and the bass amp in the corridor. All the musicians stood around the drums and had headphones and their own mini-mixers. For a few songs, we baffled Alex [Turner], the singer, because he wanted to sing live, but for two-thirds of the songs, he just played guitar and overdubbed his vocal afterward. The microphones were pretty regular: AKG D 112 inside of the bass drum; Electro-Voice RE20 outside of the bass drum; Shure SM57 on the top and bottom of the snare; Sennheiser MD 421s on the tom-toms, again top and bottom; and AKG C 12s as overheads. There were a couple of tracks on which the ride or hi-hat needed to be a bit louder, so I had a Neumann 84 on each of them. I also placed an AKG C 451 at the side of the snare drum, heavily compressed to give front end to bass and snare. We had a couple of room microphones up, but didn’t use them much.

For guitars, I generally start with an SM57 and a Royer 121 together, placed slightly off-center. It’s the perfect combination: If I want to brighten the sound, I’ll turn up the 57; if I want warmth, I’ll turn up the Royer rather than EQ things. The bass went through my favorite amplifier, the Portaflex B15, which is a beautiful valve combo, and it had a Sennheiser MD 421, and I’ll have a disused NS10 cone hanging from a stand, wired up to an XLR. Its frequency range is 20 or 30 Hz to maybe 500 Hz, which is good for picking up the low end of the bass. We used a Neumann valve M149 for the vocals going through an 1176. Half of the microphones went through the Amek desk at The Chapel Studio; the other half went through external mic pre’s, depending on what sound I liked. I used Massenburg GML 2032 for the top-end stuff because it sounds really clear, and the rest were old valve Telefunken pre’s or APIs.

Abbiss favors mixing on the vintage 16-channel EMI TG1 mixing console.

Photo: Paul Tingen

You recorded the album to Pro Tools. Didn’t you say that you wanted to get rid of computer screens?

I love tape, but it’s just too time-consuming to use it. I use Pro Tools as a tape recorder and for quick editing, very much in the same way people used razor blades years ago. I don’t use things like Beat Detective unless I’m desperate. I’ll do several band takes and will go through them and select the best sections from their best takes so I don’t need to drop in or do overdubs. The Pro Tools systems have become so much better in recent years that the sonic difference with analog is tiny and not worth the additional effort involved in using multitrack tape. I’ve always been more interested in the feeling you get from a piece of music and whether the take is great than with the technical aspects of things. But when I was mixing in the early days of Pro Tools, I found that I didn’t get the same depth of sound, whereas with tape, it all seemed to glue together.

Barny [mixer of the Arctic Monkeys album] and I did find, however, that when it came to mixing, things didn’t sound right coming off Pro Tools and through the J Series SSL desk at Olympic Studio 1. We couldn’t put our fingers on what it was, so we asked Olympic whether their old reconditioned 16-channel EMI TG1 desk was available. The desk is originally from Abbey Road and has incredibly well-made early transistor circuitry. Per channel, it has two tone controls, a compressor, a pan and a line gain, and within an hour of getting some basic EQs, it sounded much better than the SSL. Because we had only 16 channels, we had to submix stuff inside of Pro Tools. It was very straightforward and all about the balance and not about mix tricks.

Moving on to Kasabian, their mixture of soaring, electro-flavored and indie-influenced rock is perhaps more typical of the stuff you produce. How did you go about producing their new album, Empire?

The recordings took place over three-and-a half months at Rockfield Studios in Wales and involved about every strategy in the recording book. The band hadn’t worked out the entire album and arrangements before we started. There were some tracks that were maybe just an idea or a short demo, while other tracks were full-fledged songs, which often evolved into something else. It was an ongoing process of writing, arranging and recording — sometimes overdubbing, sometimes recording the whole band together. We decided on a song-by-song basis what the best way was of doing things.

Did you use a similar recording setup with the Arctic Monkeys?

It was quite similar, although Rockfield has quite a few Neumann U67s and we used a few of them. Rockfield also has a Neve with great-sounding preamps and a rack with Rosser mic pre’s, and we used both. I also hired the TG1 and took it over to Rockfield and recorded the drums through that. One half of the album is more rock ‘n’ roll and the other half is far more keyboard- and sequence-oriented. There are some bits where the two overlap, but the rest is almost done in two different styles.

How did you work with the keyboards?

I have synthesizers like the ARP 2600, ARP Axxe, a Korg MS10 and Oberheim OBXa. Almost all of the stuff that I own are toys for musicians to play with, like old tape delays, spring reverbs, weird guitar pedals, synthesizers and guitar synths. We used quite a bit of the old [Sequential Circuits] Pro-One synthesizer, which is a great keyboard. We also used an old EMS guitar synth, the Synthi Hi-Fly. It’s a white, plastic, bulbous-looking thing with 10 controls on it, and Serge played the keyboard part on his guitar and it ended up sounding halfway between a guitar and a synth. Other keyboards that we used were the OBXa and MonoPoly.

Empire‘s rockier tracks were mixed by Andy Wallace in New York. He’s known for his work with Nirvana, Sonic Youth, Jeff Buckley, Rage Against the Machine, System of a Down. What were your experiences?

I was very surprised to be met by this small, gentle, 68-year-old guy with white hair and glasses. He mixes in a very “old-school” way. He mixes the songs in about three to four hours, and it’s all about subtle bits of EQ and where the faders are. He was constantly adjusting instruments that were playing with the vocals so you could hear the vocal, and then when it stops, you can hear the instruments. He hardly had any outboard gear plugged in — perhaps a plate, a short room, a stereo harmonizer, a delay and that was it.

It sounds like you found a bit of a kindred soul in Wallace.

Yeah. He commented that in the old days, mixing would be a small percentage of recording because people made sure that everything on tape would be the best performance with the best sound. That’s also the way I work, and I realize that I’m a dinosaur. I’m not a retro person; I like to think that I make records that are current. But I realize that in the current economic landscape, studios are closing and it’s getting harder and harder to work the way I do. But as long as I can work like this, I will because I think it is the best way.

Paul Tingen is a Dutch guitarist and writer who lives in Scotland.