In the past 30 years, the fabric of radio play and record sales has been woven with hits from Mariah Carey, Eric Clapton, Josh Groban, Britney Spears, Kenny G., LeAnn Rimes, Brandy, Burt Bacharach, Toni Braxton, Marc Anthony, John Mellencamp and Michael McDonald. And if you followed the Gold and Platinum threads that lead from this A-list of artists, they would invariably lead to Mick Guzauski. Probably the best-kept secret in music production, Guzauski’s work spans a wide range of styles, including jazz, R&B, Latin, rock, pop and easy listening. And although his work has defined the word “hit” in the past four decades, he has only recently garnered Grammy praise, first winning a Latin Grammy in 2002 for Thalía’s Arrasando, then four Latin Grammys in 2004 for Alejandro Sanz’s No Es lo Mismo and, most recently, winning the award for Best Engineered Album, Non-Classical in 2006 for Clapton’s Back Home.

Photo by Ellen Guzauski

Guzauski got his start in the ’60s in his parents’ basement in Rochester, N.Y., doing pickup engineer work with such talent as Steve Gadd and Tony Levin — then students at the Eastman School of Music — and Lou Gramm, another Rochester native who was then playing in local bands and was soon to hit it big with Foreigner. Around that same time, Guzauski worked on the first recordings for Chuck Mangione — another Rochester native son who was soon to make his mark. Guzauski would continue to work on and off with Mangione throughout his career, eventually engineering Mangioni’s breakout hit, Feels So Good (1977).

I had the good fortune of being Guzauski’s assistant engineer on a number of projects from 1988 to 1992, so I was glad to catch up and learn how things have changed for him over the years. He spoke with me by telephone from his 1,400-square-foot studio in the basement of his home in Mt. Kisco, N.Y., about an hour north of New York City, where he has been making music for the past 12 years.

How has your career evolved along with the business in the past decade?

Starting in 1993, I was working mostly for Tommy Mottola when he worked for Sony. In the ’90s, the projects I did were mostly pop female ballads; now I’m getting to do a lot more rock and more variety. After [Mottola] left Sony, I became more of an independent guy. Since 2003, it’s been the responsibility of my manager, Joe D’Ambrosio, or me for finding work. I’ve been taking more meetings and seeing what projects are available. It’s not just me sitting down here and people telling me, “This is what you’re going to do next week.”

In the past few months, I mixed the Cream reunion album Cream: Royal Albert Hall, Eric Clapton’s Back Home, a Universal artist named Res and a band called Hurt from Capitol. I still like doing the big ballad stuff, but variety keeps it interesting.

As far as the gear, I’d have to say that Pro Tools and other workstations have made the biggest change in the whole recording industry. Now tracks are recorded at home, and at the very least they do their overdubs at home.

With the shift more toward the home studio, are the tracks you’re getting better or worse?

It is still variable. When it was on tape, there were some incredible tracks and there were tracks that needed a lot of work to get things sounding right, and it’s still the same now. There’s a slightly different set of problems. In the old days, problems were either electrical noise or analog tape noise or malfunctioning gear. Now I hear more acoustical problems. Like if there’s a distant-miked acoustic guitar or background vocals, there may be a lot of acoustic background noise or very strange room responses.

How about audio being delivered via MP3? Has that changed your methods at all?

A lot of people have said that this has become an MP3 industry and fidelity has gone down, but I don’t think that’s really true. The compressed audio formats have replaced the cassette as a portable audio format. I think people still use CDs at home, and if they used cassettes, now they use an iPod at home, which is quite a bit better. I really don’t see where that’s become a quality problem, because people who still want high fidelity use an uncompressed format, and I think the general delivery format of AAC for portable is generally a big improvement over cassettes.

For me, not having to think of something being distributed on a cassette has helped. Cassettes would saturate very easily at high frequencies, so you’d have to watch out how much high-frequency energy you would put on it. With MP3s, you have to watch how much you put on there because things get harsh, but you’re not really up against a technical wall.

You’ve recently won some Latin Grammys. How do those tracks differ from other work you’ve done?

In 2003, I did an album for Alejandro Sanz, and last summer I did a record for Ricardo Arjona with a producer named Tommy Torres. That was one of the albums where I was incredibly impressed with the tracks that came out of a home studio. The drummer on the project, Lee Levin, has his own studio with Pro Tools and API preamps. He has his whole drum set at home, and he does the tracks there and they sound as good as anything I’ve heard. Most of the record was done in home studios and it sounds first-class.

Does your style change for the Latin market?

I’d say I mix more for the song. I don’t want to be too general, but there are some Latin songs that want to be more lush and reverby, and some are more dry and in your face. To me, that is the style I relate to naturally, so it wasn’t a stretch. I really like Latin music even though I don’t understand a word of it. Musically, there’s a certain fire in a lot of it that is very enjoyable. I love Latin projects.

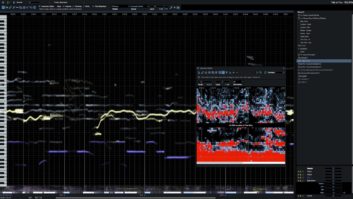

How about the gear? What’s in your studio now?

I have a Sony Oxford in the control room and a Pro Tools HD system with Accel cards. That’s converted to MADI, so I have all 96 channels going directly into the console. Then I use my old MIXplus system as a mix machine to keep all the stems and different versions of the mix on one session, just to keep things neat. I also have a second room with a Pro Tools HD system and a Yamaha DM2000 console. That room is set up so my assistant, Tom Bender, can organize files while I’m working on a mix in the other room. Also, it’s great for when producers come over so they can be working on editing and tuning while I’m mixing.

Are you running into a brick wall with respect to the Oxford because it’s not being made any longer?

Not yet. They stopped making the Oxford in 2003, and Sony has a policy of supporting discontinued products for seven years. The console has been very, very reliable aside from having to replace a few switches and some defective display drivers for the LCD screens.

It sounds like you dig the console.

Yeah, because the automation is so comprehensive and easy to use, and it just sounds good; it’s very transparent. With the way things are now, when someone sends me a mix to do — and more often than not the producer, artist and A&R guy are not there — it’s essential that I be able to do a quick recall. With the console and Pro Tools, it’s really easy. I also like having a console rather than just mixing in Pro Tools. When I get a project in that I’ve never heard before, it’s nice to have all that processing on every channel without having to assign it or build it when mixing in the box in Pro Tools. It’s like an analog console.

The combination of Pro Tools and the Oxford works really great. Things that I need to do graphically with Pro Tools I can do before the console and it’s not reflected on the console’s faders. So I can clean stuff up and then use the console just as a creative tool to mix.

Do you like any of the new controllers that are available?

I’ll be trying out a Digidesign D-Control soon. I’ll set it up in my second room. I’ve got to learn that and see what it does because I think that really is the future of things right now. The Oxford still has some life in it, and I think that control surfaces for audio workstations have a ways to go before they have the flexibility of a real console.

So are you using Pro Tools strictly as a playback machine or do you use a lot of plug-ins?

I don’t use too many plug-ins. I mostly use the EQ and compression in the Oxford, and I have quite a bit of analog outboard gear when I need it. For compression, I have 1176s, Distressors, Fatso Jr. and dbx, along with Weiss, Manley, GML, Calrec and Neve EQs.

The Eventide SP2016 was your go-to ‘verb for a lot of mixes when we worked together.Are you still using it?

I still use them quite a bit. In recent years, on a lot of music, things have tended to be quite a bit drier. The Eventide is very good for sparkly, long reverb on vocals; I still use it on ballads. A lot of times, I’ll use a short room or a delay. I’m using a lot more variety since I’m mixing a larger variety of music now. I also like the Sony DRE-777 sampling reverb, which they don’t make anymore. It has some very natural-sounding short rooms and long rooms. I can put it in a mix and it doesn’t sound like you’ve put artificial reverb on something

You’ve done quite a bit of surround work. What’s your approach?

I love mixing surround because you have so much space to place things; you get a clarity that is very hard to get in stereo. Most of the surround stuff I’ve done is more about generating a believable live show, like the Cream concert I mixed. When it was recorded, there were four pairs of room mics around the theater. I worked with that and the band to create what you’d hear in about the tenth row. I’ve also done 5.1 mixes for all the other Clapton records I’ve done and some Michael McDonald records, which are more studio records repositioned for 5.1.

There are other surround projects where I got more inside the band, [but those] will probably never come out for political reasons. One was Michael Jackson’s Thriller. The changes with Sony and with Michael mean that will probably never come out, but that was a lot of fun.

Guzauski won his first Grammy Award this

year, for Eric Clapton’s Back Home album.

Courtesy naras®

Do you use the center channel a lot or do you treat it more as a quad mix?

As a matter of course, I usually have some of the kick, bass, snare and lead vocal in the center, all dry. The vocal there to focus the center; the kick, snare and bass there because you have three speakers in front and getting that much more cone area moving means you can get a little more punch. Usually, anything that’s going to move around or offset from center I don’t use the center speaker. I don’t usually pan anything between center and right and center and left; I use the left and right as a stereo pair in that case.

When you do a surround mix, do you start with the surround and then go to stereo after, or vice versa?

If I get a project I’m only going to do as a surround mix, I listen to the original record then try to set up a surround mix that feels similar to it. If I’m doing two mixes, I’ll start with the stereo first and then pan stuff out and modify it as needed.

Where did this whole thing start for you?

When I was a kid and I listened to records, I was interested in how they were made and how they were recorded. My first gig, when I was in high school, was in a hi-fi and record store in Rochester. People would trade in stuff and I’d get old tape recorders and fix them and I built a little studio in my parents’ basement. I built a little — I wouldn’t call it a console — but a little mixer, and I’d overdub by tracking live to stereo on one stereo machine and then bounce to another machine while we did vocals. I engineered demos for local bands like that.

Later on I got a 4-track half-inch machine. At that time, I got to work with some very good people. I worked with Steve Gadd and Tony Levin on some different sessions and with Lou Gramm of Foreigner, who was then playing with some local bands, all in my parents’ basement. That’s how I started out in the late ’60s.

A lot of great music and musicians came out of that area that propelled a lot of careers. Tell us about that.

At the time, Rochester had a really great music scene. There were a lot of clubs, and in ’69, ’70 and ’71, the Eastman School of Music had [one of] the first recording engineering courses in the country. Phil Ramone taught and I’d go to the summer courses, and that was the introduction to the professional part of the business. It was a great thing back then.

I was also working for a sound company and did a lot of the live mixing for [Chuck] Mangione around the area. At the same time, we’d record some of the same concerts. His first album at Mercury Records, called Friends and Love, I recorded with the 4-track I brought up from my parents’ basement. I hooked it up to the P.A. mixer, and back then it was separate mixers, not a console; we had several Ampex MX35 mixers. That was my first recording for him. We mixed that in my parents’ basement.

I have that record on vinyl. How did you get such a great sound and separation from just four tracks?

One track was the whole rhythm section; one track was the whole right side of the orchestra, brass and reeds; the third track was the left side of the orchestra; and the fourth track had all the solos and vocals. We had audience mics out in the theater that were across the brass and string tracks since those were the ones that were going to be panned left and right.

We used any mics we could find. We had anything from the consumer versions of the SM57s, the chrome ones, on up to U67s. Anything we could borrow and use. It was a major concert for him at that time, and we recorded it just sort of for the hell of it, but it ended up being released.

How did you make the transition from Rochester to L.A.?

In ’75, [Mangione] brought me out to L.A. to engineer an album [of his] called Chase the Clouds Away. We recorded 45 players live in A&M Studio A. At that time, it didn’t have any of the vocal booths; it was just one huge room. We did the whole band live, leakage and all. That was the first time I used a 24-track machine. He asked me, “Do you think you can handle the gig?” and I didn’t think I could, but I wasn’t going to say that because I was going to lose the shot, and it worked out really good.

All the time I was out in L.A., I was meeting people and making contacts. One of my L.A. gigs when I first moved to town was with a band called DFK. It was Andy Johns’ project, produced by James Newton Howard. Andy had a scheduling conflict, and James hired me to do some overdubs.

Eventually, in ’78 I moved to L.A., and just to support myself I took a night tech job at Larrabee for a while. A good friend of mine from Syracuse [N.Y.], Jim Fitzpatrick, was running the Westlake Studio on Beverly Boulevard. He called me up and I started meeting a lot of producers and artists. Westlake was a nice hang at the time; I got gigs there by hanging out. I did a lot of work for James Newton Howard at the time, I met George Massenburg, and did a lot of work for Earth, Wind & Fire’s label and did three records for them. I also worked with Valerie Carter, Prince and D.J. Rogers.

I was also called to do a record for Average White Band, with Jay Gruska producing, and he wanted to work at Conway. That’s where I met Burt Bacharach and did “That’s What Friends Are For” with him, as well as Patti LaBelle’s “On My Own.” At that point, in the mid-’80s, I started getting calls for being a mixer. I did a lot of work for Peter Bunetta and Rick Chudacoff, who were producing a lot of records there. I mixed for Smokey Robinson, Talking Heads, Welcome to the Real World for Mr. Mister. So that was really the beginning of my mixing career. I used to work a lot at Lighthouse, Conway and Devonshire then.

And that brings us full circle, back to Sony in the early ’90s. How did you eventually get back to New York?

I was doing a lot of work with Kenny G. and Michael Bolton in L.A. at the time, and Walter Afanasieff was producing a lot of cuts. They suggested he try me out. We did some work, and Walter was producing most of the Mariah Carey records. Tommy [Mottola] heard me and really liked my work, so I was going back and forth to New York. He wanted me to move to New York, and at the time, I didn’t want to make the move. But after the earthquake hit, we — especially my wife — decided we were going to move back to New York.

Kevin Becka is Mix‘s technical editor.

On mixing the 5.1-channel version of Michael Jackson’s 1982 masterpiece, Thriller:

On the surround mix for Eric Clapton & Friends’ Crossroadds Guitar Festival, held July 2004

On working with producer Simon Climie to mix B.B. King’s Reflections album

Discography

E=engineer; M=mixer

Yolanda Adams:Mountain High…Valley Low (1999, M)

After 7:Reflections (1995, M)

Christina Aguilera:Mi Reflejo (2000, M), I Turn to You (2000, E/M), Christina Aguilera (1999, M)

Anastasia:Pieces of a Dream (2005, M)

Marc Anthony:Mended (2002, M), You Sang to Me (2000, M)

Tina Arena:Souvenirs (M), In Deep (1997, M)

Babyface:Everytime I Close My Eyes (1996, M), Day (1996, M)

Backstreet Boys:Millenium (1999, M)

The Bee Gees:Love Songs (2005, M), Still Waters (1997, M)

Michael Bolton:Til the End of Forever (2005, M), Timeless: The Classics, Vol. 2 (1999, M), All That Matters (1997, M), One Thing (1993, M), Time, Love & Tenderness (1991,M)

Boys II Men:Ballad Collection (2000, M), Extras (1999, M), II (1994, M)

Brandy:Never Say Never (1998, M)

Toni Braxton:Un-Break My Heart: The Remix Collection (2005, M), Secrets (1996, M)

Jim Brickman:Valentine (2002, M), Destiny (1999, M), Visions of Love (1998, M), Picture This (1997, M), Gift (1997, M)

Sarah Brightman:Harem (2003, M)

Mariah Carey:Merry Christmas DualDisc (2005, M), Charmbracelet (2002, M), #1s (1998, E/M), Butterfly (1997, M)

Ray Charles:Thanks for Bringing Love Around Again (2002, E)

Cher:Chronicles (2005, M), Heart of Stone (1989, E)

Eric Clapton:Back Home (2005, M), Me and Mr. Johnson (2004, M), One More Car, One More Rider (2002, M), Reptile (2001, M), Riding With the King (2002, M), Pilgrim (1999, M)

Stanley Clarke:If This Bass Could Only Talk (1988, M), Hideaway (1986, M)

Natalie Cole:Snowfall on the Sahara (1999, M), Everlasting (1987, E/M)

Earth, Wind & Fire:Love Songs (2004, E), Essential Earth, Wind & Fire (2002, E), Millennium (1993, M), Powerlight (1983, E/M)

Warren Hill:Life Thru Rose Colored Glasses (1998, M), Shelter (1997, M), Truth (1994, M), Devotion (1993, E/M)

Patti LaBelle:Flame (1997, M), Burnin’ (1991, M), Be Yourself (1989, E/M), Winner in You (1996, E)

Jennifer Lopez:Jenny From the Black (2002, M), I’m Gonna Be Alright/Alive (2002, M), On the 6 (1999, Remixing/M)

Chuck Mangione:Fun and Games (1979, E), Children of Sanchez (E/M/editing), Feels So Good (1997, E), Chase the Clouds Away (1975, E)

Brian McKnight:U Turn (2003, M), Superhero & More (2002, M), Superhero (2001, M), Anytime (1997, M)

Laura Pausini:From the Inside (2002, M)

Prince:Best of Prince (2006, E/remixing), Hits 2 (1993, E), Hits 1 (1993, remixing), Controversy (1981, E)

LeAnn Rimes:You Light Up My Life: Inspirational Songs (1997, M)

Smokey Robinson:One Heartbeat (1997, M), Intimate (1999, M)

Jessica Simpson:Sweet Kisses (1999, M), Irresistible (2001, M)

Britney Spears:In the Zone (2003, M)

Barbra Streisand:Emotion (1984, E), Till I Loved You (1988, E/M), Higher Ground (1997, M), Duets (2002, M)

Talking Heads:True Stories (1986, mixing assistant), Best of Talking Heads: Once in a Lifetime (1992, M), Talking Heads Brick DualDisc (2005, M), True Stories DualDisc (2006, M)

Vanessa Williams:Sweetest Days (1995, M), Star Bright (1996, M), Next (1997, E/M), Greatest Hits: The First Ten Years (1998, M)

The Yellowjackets:Live Wires (1991, E/M), Like a River (1992, E/M), Run for Your Life (1993, E), Collection (1995, E/M), Priceless Jazz (1998, E)