Pete Reiniger

No trip to D.C. is complete without visiting the Smithsonian. From Washington’s uniform to Dorothy’s Ruby Slippers to Pollack’s paintings, essential artifacts of our national culture have been curated there since 1846. So as part of our “visit” to the D.C. audio community, we called on Pete Reiniger, chief engineer at Smithsonian Folkways, the nonprofit record label of the National Museum.

Smithsonian Folkways is “young” compared to the Institution as a whole. It was created after the acquisition of Moses Asch’s Folkways label in 1987. (Folkways was started by Asch in ’48.) Today, Smithsonian Folkways holds the catalogs of several labels, amounting to more than 3,500 titles.

Reiniger works on the majority of new releases that carry the Smithsonian Folkways imprint—sometimes recording and/or mixing, sometimes mastering only. “If I track and mix a project, I’ll bring it to another studio to be mastered because it’s best to have another pair of ears,” he says.

Four Smithsonian Folkways projects are nominated for Grammys this year: new albums by singer/songwriter Elizabeth Mitchell and Latin folk/rock band Quetzal, a banjo–centric album by Stephen Wade, and Woody at 100, a three-disc collection celebrating the centennial of Woody Guthrie’s birth.

Reiniger flew to L.A. to track Quetzal’s Imaginaries (nominated for Best Latin Rock, Urban or Alternative Album) in Joel Soyffer’s Coney Island Studios. Led by singer/multi-instrumentalist/composer Quetzal Flores and his wife, musician/composer/singer Martha Gonzalez, Quetzal combines traditional Latin instruments with rock music and Gonzalez’s jazz-leaning vocals.

“Two engineers working at the studio, Alberto Lopez and Camilo Moreno, helped on those sessions,” Reiniger recalls. “Camilo is also all over that album as a percussionist.

“We recorded to Pro Tools, but with everything passing through the electronics of a 24-track analog tape machine. That enhances the sound in an analog fashion. The Massenburg mic pre’s were a big plus. Everything was tracked separately, with many instruments done individually as overdubs, particularly the percussion. We started Martha’s vocals in an isolation booth, but I could hear the room tone, so we moved her out into the big room.”

Reiniger has developed a philosophy about miking unfamiliar instruments, like some of the folk pieces he encounters: “Never mike an instrument you haven’t first listened to acoustically. After that, it’s just physics as to microphone selection and placement.”

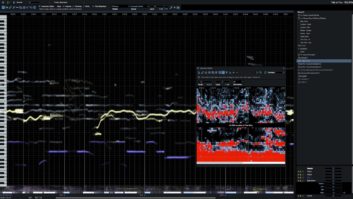

Reiniger brought the Pro Tools files back to D.C., where he works on a PC-based Cube-Tec AudioCube system fitted with Nuendo and WaveLab. “I’ve used Nuendo for years and prefer mixing in it,” he says. “But on the title track, we briefly exported the intro into Pro Tools because Quetzal wanted an old radio-type sound that he knew we could create with a plug-in in Pro Tools, then brought it back into Nuendo.”

Reiniger sends his mixes to Airshow. “They do a great job. I’ve been working with David Glasser and Charlie Pilzer for years,” he says.

For in-house mastering projects like Woody at 100, Reiniger says, “The rig is the same, but I use WaveLab for editing. All the restoration plug-ins are from AudioCube.” Reiniger appreciates AudioCube’s Spectrapolator, which allows him to select and remove anomalies at specific frequencies. Restoration tools also include a Declicker, a Dehisser, a Debuzzer to take out AC hum, and a Repair Filter, among others. “Brickwall EQ is another mastering and restoration tool, but I use it sometimes in mixing, too, because if you have a lot of extremely low frequency and you want to get rid of everything below 30 Hz, say, you can get rid of it by selecting a highpass filter.”

Many of the tracks on Woody at 100 were previously remastered for Smithsonian Folkways’ releases and simply had to be sequenced and balanced. Some were cleaned up a bit more. About a third, however, were previously unreleased songs that had to be transferred, restored and mastered.

“Our philosophy on remastering and restoration goes back to reissuing the Anthology of American Folk Music, which we did in 1997,” Reiniger says. “There were people who wanted us to get rid of all the noise, but our attitude is, if it starts digging into the music, we will stop. If that leaves a little hiss, you live with the hiss. Sometimes we’ll find what we call a ‘once around,’ a swishing sound that you get from discs; that’s almost impossible to get rid of because it’s not a steady-state frequency. That would have to remain. I’m trying to make historical recordings more listenable to a contemporary ear—for people who may not even remember LPs let alone 78 rpm transcription discs. But I always approach with caution, because we don’t want to do any restoration work that will compromise the musical content.”