Theater of the Mind was given the surround treatment in addition to its original release format.” />

Ludacris’ Theater of the Mind was given the surround treatment in addition to its original release format.

Like a lot of people in this industry, when I first heard The Eagles’ “Seven Bridges Road” remixed in 5.1 surround at an AES show in what now feels like a lifetime ago, I was convinced that surround had arrived! With home-theater systems flying off the store shelves, high-profile mixers suddenly landing surround assignments left and right, conferences exploring the topic and even a slick magazine dedicated to the art form, it seemed like a can’t-miss trend.

But it didn’t catch on. As is often the case with developing technologies, there were format wars (SACD vs. DVD-A), confusion about player compatibility (will it play on my DVD-V player or do I need new hardware?) and, even after a few years, disappointment with the paucity of titles available. Quietly, the trumpet fanfares died away with the formats themselves, and the studios that had put in 5.1 mix rooms looked for film and videogame work to use their full capabilities.

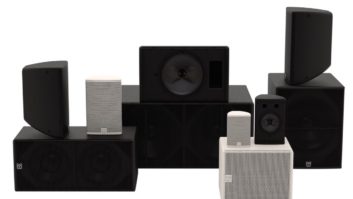

But now there are stirrings again in several quarters. Various specialty labels are quietly putting out surround discs or offering surround downloads, and the momentum seems to be building anew. One perhaps unlikely player in this brave new world of surround is a company better known as a hardware manufacturer than a record company. Monster Cable, which began 30 years ago as a maker of high-end audio cables, has diversified to include everything from loudspeakers to computer, videogame, and portable audio and video accessories. In 2005, it introduced Monster Music, a record label dedicated to releasing 96kHz surround products. Under the stewardship of company founder Noel Lee, who is also an engineer and musician, Monster Music put out a handful of releases in its first three years, including the Grammy-winning George Benson/Al Jarreau disc Givin’ It Up, a live album from 3 Doors Down called Away From the Sun and 5.1 remixes of a couple of classic discs, one old and one recent — the Vince Guaraldi Trio’s A Charlie Brown Christmas and Ray Charles’ Genius Loves Company. And now comes the release Lee hopes will take Monster Music from its boutique audiophile status to a more commercial level: David Rideau’s remix of last fall’s Ludacris hit album, Theater of the Mind.

Of course, having a record label that specializes in surround releases benefits Monster in a couple of ways — after all, a good 5.1 system needs lots of quality cable, right? (Lee even admits that the format wars and special players required by the first-gen surround releases “was great for our company — but not for many other people.”) But beyond that, Lee genuinely seems to want to exploit the surround medium because “it’s amazing! Anyone who hears it agrees. And now, a lot of the technical barriers are diminished — not gone, because you still have to have the speakers around the room. But you can get a standard DVD player to play the format. All the releases we’ve had so far have been DTS and Dolby Digital, so you can choose the audio quality you want. There’s already been good acceptance of surround with films and games; our goal is to bring music along, too.”

As for the decision to partner with Ludacris, Lee notes, “We needed a relevant performer who would connect with today’s mass audience and also be a spokesperson for the format. We spoke to many different people, but it was Luda who said, ‘I want to be the first artist in the hip-hop genre to break into 5.1 HDS surround. [HDS is the Monster format’s trade name.] So we talked to him for a long time when he was planning his Theater of the Mind album, and he was really enthusiastic — ‘Yeah, let’s do it!’ And after he heard the mixes, his mind was totally blown.” An added bonus is that Theater of the Mind was released both as an HDS DVD and in 7.1 Blu-ray with added HD video footage.

David Rideau on working on this remix: “There’s a general plan you follow, but also a lot of it is inspiration as you get into experimenting with panning.”

The choice of Rideau as the mixer of the project would seem to be a natural: During the course of his 30-year career, he’s engineered and/or mixed for a who’s who of R&B and smooth-jazz artists, such as Shalamar, George Duke, The Whispers, Earth Wind & Fire, Babyface, Gladys Knight, Janet Jackson, Patti LaBelle, Boney James, George Benson, TLC, Larry Carlton, Lionel Richie, Al Jarreau — it’s a long list, but admittedly short on rap names. He has done several surround projects in the past, however (his favorite is the 2004 Live Sessions by the West Coast All-Stars, featuring Tom Scott, En Vogue, Chris Botti and others), and he relished to chance to work with a mainstream rap artist like Ludacris.

Theater of the Mind gave Rideau a wonderful playground in which to work. Alternately serious and lighthearted, poetic and profane (sometimes both at the same time), the album has the Atlanta-based Ludacris as the master of ceremonies in a string of pieces that are socially conscious one moment and darkly humorous the next, and which paint vivid portraits of street characters and the requisite tough-and-tender heartbreakers; all the while, Ludacris himself boasts and jokes and chides and occasionally gets real serious. The guy’s got a million one-liners — many of them based around sports imagery — but he also lets his impressive list of guest rappers and speakers bring their own flava to the party, including T.I., The Game, the ubiquitous Lil’ Wayne, Ving Rhames, Spike Lee, Chris Brown and T. Payne. Sonically, the album was already a marvel before Rideau got to his surround mix, with loops and sequenced parts and voices and effects all bursting forth in unexpected and often playful ways. Kudos to the 17 engineers and six mixers listed in the credits.

I asked Rideau to lead me through his approach to a project like this: “The first thing you do is listen to it with great attention in the stereo form,” he says. “And while you’re listening, you’re thinking, ‘Maybe I can break out these talking voices over here and to the rears, and maybe I can bring this effect or this reverb to the rears.’ There’s a general plan you follow, but also a lot of it is inspirational as you get into experimenting with panning.

“The sequence of events in this case is, after I listened to the record really closely, I requested to all the producers and engineers and mixers, and I put the word out to the record company, that in a perfect world, I’d love to have [Pro Tools] stems of everything. Now that’s an instant turn-off for most mixers because it’s a lot of extra work. If you can imagine how many elements there are in a song.

“Some things were simpler, but the average would be at least 40 passes of a five-minute song. What happens is, for every element that you like to have a separate stem for — kicks, snare, hi-hat, other percussion, background or lead instruments; whatever — in a perfect world, what a remixer like myself would get is off the stereo bus: That element solo’ed, and at the same time I’m also getting the effects — whatever treatment is on that element, I’m getting the stereo version of that on a separate track. It’s a lot of stuff — it’s more than an ocean. Some mixers sort of do it automatically — Dave Pensado, Manny Marroquin [both mixers on this album] — they’re buddies of mine, so when I call over to the studio, and say, ‘Hey, I need stems,’ they’re like, ‘Okay, they’ll be there in an hour.’ And it also makes a difference when you have a nice studio with assistants who can do that stuff for you.

“But in some cases, with guys like me who do a lot of mixing in my own studio, you call, and say, ‘I need stems.’ and it’s, ‘Oh, my god!’ So with the guys who didn’t automatically print stems, I would go through each song and try to get the bare minimum of what I’d like to have separate. Needless to say, I wanted a lot, but in some cases I know you can have five things making a backbeat that I don’t have to have separate. Anyway, I went through and made lots of notes on the stuff that I wanted, and the guys were for the most part very accommodating and very cool. In some cases, guys even said, ‘The track is so simple, I’ll send you the entire session and you can work off the session,’ and that worked fine, too. There were three or four of the tracks that I started from scratch myself, and I either derived panning from the session itself or in some cases I did the stems myself from the sessions.”

How closely did you replicate the feel of the stereo mix? “My Number One goal, personally, is not to have any of my buddies pissed off at me; that’s where I’m starting from,” Rideau says with a laugh. “Because I’m a mixer, I know how it is — you put your heart and soul into a project, and the producers and writers and artists all have visions, and I don’t want to screw that up. I’d like to enhance it.

“It’s not a remix where you’re saying, ‘All right, I’m erasing everything but the vocals and bringing in a new guitarist!’ I didn’t do any vocal overdubs. I made it clear from the outset my intent was to preserve what they had done and make it more exciting for a new format. That said, there were times when I added some effects — a little bit of room in some cases, a little bit of delay — but it’s not that obvious; it’s a dimensional thing. You take something that’s in the front spectrum and you take it off by itself as an element, and all of a sudden it’s naked. So my idea was to try to have it sitting in a space that’s maybe created by another instrument. You might have percussion or something that’s dry because it’s sharing a space with something else that has a room or a tail of some kind, and it doesn’t seem like it’s dry as a bone, but you pan it to left-surround, and it’s like, ‘Here I am! I’m naked!’”

At Rideau’s L.A.-area personal studio, Cane River Studios, “I did some premixes and got things generally organized and figured out conceptually where I wanted to put some elements and did some experimenting on placement,” he says. But for the main mix, he traveled north to Studio 880 in Oakland, in part so that Lee, who works across the San Francisco Bay, could give his input. “Studio C there has a [Digidesign] ICON 32-fader with a surround package on it, and that was ideal for this,” Rideau says. “I had everything I needed, especially after I tortured them with six hours of setting up monitors — I’m really critical with the setup for surround and Noel is hypercritical. Part of Noel’s thing is he wants to be able to get not only the five discrete panning positions of the five surround speakers, he wants to have the five discrete phantoms in between each of those pairs, and if I can’t make that happen, he wonders what’s wrong because that’s part of his HDS concept. I had JBL LSR monitors, which were great, and Monster also has their own speakers, so I had both sets and I definitely used them both.”

Though Rideau says that when he’s mixing at home, “I’m generally an out-of-the-box kind of guy, in surround I’m exclusively in the box because that’s the only manageable way for me to make it happen — because it’s recallable, it’s totally automated and also because I’ve got some cool plug-ins!

“I can do a lot with just a mouse,” he continues, “but when I’m getting to the crazy stage — as I like to call it — at that point I’d like to have a joystick. And Noel Lee requires a joystick. [Laughs] He will not go into a studio that doesn’t have one! ‘Okay, take that and move it over here and back over here.’ Noel wants it to be exciting. He wants it to be dynamic — not to the point where it’s distracting, but to where it’s helping emote the feeling of the song.

“I felt like we could take some chances and be creative with panning and effects because the title of the record was Theater of the Mind. One of my favorite tracks is called ‘I Did It for Hip-Hop,’ and there’s a point where a guy does one of the most amazing scratch solos you’ll ever hear. As soon as I heard it, I thought, ‘Oh, my god!’ and on the next pass I grabbed the joystick and did a light pass in his solo going crazy, and it was quite a rush. The whole thing was just so much fun. I’ve never laughed so much working on a project. That Luda is a very clever fellow.”

Rideau also has high praise for Lee: “He has some of the best ears in the business; he’s a real visionary. It’s rare to have a guy that geeky, like me, and passionate, like me; it’s a weird combination of things. And to have a company he started in his garage for $1,500 and making it into what it is today — you have to have a vision. You can see it in projects like this. It’s more than just a business to him.”

But it is also a business, as Lee freely acknowledges. One of his goals with the Ludacris remix, he says, is “to proliferate the format through our retail channels to the Monster Cable audience, so hopefully there will be enough people who will say, ‘That’s a great thing! Boy, when’s the next one coming out?’ It remains to be seen whether you can make a business out of it. I’d say the business model is still not there yet completely. We’re not looking at is as a major revenue stream for the company; we’re just looking at it for enhancing the canvas that artists can create on and give people a phenomenal musical experience they can’t get any other way. By that measure, at least, it’s already a great success.”