Paul Blakemore

How did your background in conventional recording prepare you for mastering?

In myriad ways. I’ve done just about everything you can possibly do in professional audio in the past 34 years, and if you understand all of the processes that are involved in making a recording, that’s infinitely helpful in mastering. Actually, a lot of people who are mixers and recording engineers don’t make very good mastering engineers because they can’t embrace somebody else’s methods or point of view about making a recording. In mastering, you have to expose yourself to so many different kinds of music and recording styles and embrace what’s in front of you.

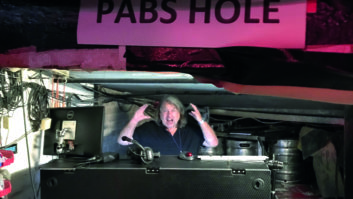

You work in Cleveland in what was once the main studio of Telarc Records, which is now part of CMG. Tell me about what you have in your room.

I have ATC 150s for my main monitors and other smaller ATC speakers to fill in for the surround setup, though we haven’t been doing much surround work recently. For PCM work, I’m a huge fan of Magix’s Sequoia [DAW]. It’s an amazing program you can make behave like Pro Tools or SADiE or Sonic Solutions; you can make it be whatever you want.

That all lives in a machine room, and you can access all of the computers and have keyboard/video/mouse control over them with this Raritan KVM switcher. This particular one is 16-by-4, so you can put 16 computers on it and have four user stations. And just by doing a couple of keystrokes, you get a menu of all the computers that are hooked up, and by selecting one, it transfers the keyboard video and mouse to that computer. It makes for an extremely flexible setup. There’s also a Z-Systems [Digital] Detangler for all of the AES routing that is remote-controllable with another CPU. So it’s a pretty powerful post-production facility in a fairly small space. I was co-designer and supervised construction.

For DSD playback, I have both Meitner and DAD A-to-Ds and D-to-As. The DAD AX24 also does PCM. I usually monitor PCM through a Prism DA2, and when I’m doing analog sample rate conversions — which I prefer to any of the digital downsampling things I’ve heard — I use a DCS 955 DAC, which is a really beautiful-sounding DAC they don’t make any more, and I have a Lavry AD122. I also have a custom 44.1 PCM A-to-D converter called Tandem 20 that has been a key component of the Telarc sound since the early 1990s. It was built by Ken Hamann. Thomas Stockham, who invented the Soundstream digital recording system, also contributed to the design. It has been used on virtually every Telarc CD release since the early ’90s, as well as on the PCM layer of many of Telarc’s hybrid SACD releases. For each project, I do multiple test recordings with different combinations of D-to-A and A-to-D converters and — this might sound a little arcane — different kinds of interconnect wire.

There are a couple of plug-ins I’m fond of that anyone who does this sort of work should investigate. Cube-Tec makes a digital equalizer called the VPI analogEQ that is really greatsounding. And the other is their very simple-to-use but highly effective dynamic range plug-in called the Loudness Maximizer.

Can you talk about the difference between mastering classical and non-classical projects?

Within classical there are two different kinds of releases. There are the audio purist releases where you do very little, if any, tinkering with the dynamic range of the music — where the idea is to preserve the dynamic contrasts that are in the musical performance, bearing in mind that hearing it coming out of loudspeakers is not the same as hearing it in a concert hall, so there are going to be some minor adjustments needed — but largely maintaining a dynamic range almost as wide as the actual performance, which can be 50-plus dB. Then there’s another kind of classical release that’s targeted to a sort of “entertainment classical” audience — like what you might put on at a dinner party or listen to in your car or something. Those require some dynamic range control, though nothing as aggressive as what you’d find on an R&B record, for example. For those kinds of releases, I usually target something in about a 20dB dynamic range.

Also, in classical mastering, most of the dynamic range control is done essentially by fader-riding — not necessarily an actual fader with your finger on it, but the equivalent result, and when you do that you’re probably going to end up with some peak problems. For the really straight classical stuff, often there are no devices used for peak control. Occasionally I will use a good peak limiter, but more often you actually use an editing approach to controlling peaks because they’re often really short in duration — a few milliseconds — so doing a chop and reducing the volume of a peak manually can be very effective. If you just take care of those two, three, four peaks with manual peak editing, you can raise the average volume of the whole thing without messing with the music’s internal dynamics.

Blair Jackson is Mix’s senior editor.