Call it the George Martin Syndrome: The famed producer enjoyed a glorious career spanning five decades and dozens of acts ranging from classical to comedy to jazz, yet he will forever be known, first and foremost, as “The Beatles’ producer.” And why not — his Fab Four productions changed the world. For L.A.-based engineer Mark Linett ([email protected]), it’s a different problem: “I don’t really mind being pigeonholed as the guy who only works with Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys — I love and am proud of all those projects,” he says good-naturedly. “But I did just finish tracking a new album for the Red Hot Chili Peppers, which is pretty far from a Brian Wilson production. Although,” he adds with a chuckle, “[producer] Rick Rubin asked me to do that project because he loved the sound of Smile so much.”

Having worked with Wilson for nearly 20 years, Linett has become inextricably linked with the Beach Boy’s remarkable recorded legacy. He spent much of the past two years devoted to Wilson’s famed Smile project: a completely new construction of his never-completed “Teenage Symphony to God,” which Wilson worked on but was ultimately forced to abandon in the mid-’60s. A huge band that could play the elaborately arranged tunes live was put together (and recorded at the premiere performance in London) and then the actual album was cut in Los Angeles (earning Linett a richly deserved Grammy nomination for engineering). This was followed by more live shows, including one at Carnegie Hall, which was broadcast by NPR and has been nominated this year for a TEC Award.

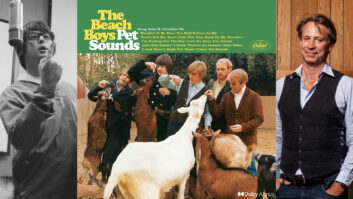

Mark Linett in his studio, Your Place or Mine

If that’s not enough, he also engineered and produced the music for Wilson’s superb DVD of Smile (which also includes a documentary about the project), which was released in the spring of 2005. Finally, last spring he engineered Wilson’s Christmas album, which was released last month on J Records. And all this was on top of many years of engineering and producing numerous Beach Boys releases — remastering their entire catalog, supervising anthologies and live recordings, and shepherding a variety of Wilson’s other projects, from solo albums to Pet Sounds Live.

But in an audio career dating back to the early ’70s, Linett has engineered, produced and mixed a plethora of fine albums by top-name artists and talented indies alike, including Rickie Lee Jones, Jane’s Addiction, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, Dave Alvin, Ry Cooder, Michael McDonald, Arlo Guthrie, Paul Simon, Randy Newman, Jimi Hendrix (posthumously, of course), Eric Clapton, The Blasters, Beat Farmers, Rosanne Cash, Buckwheat Zydeco, Crash Test Dummies, Jerry Lee Lewis, Los Lobos and a whole mess o’ others. Besides his recent tracking dates with the Peppers, Linett had just finished a live album for Alvin (with whom he won a Grammy in 2002 for his album Public Domain), another for the X and Blasters spin-off, The Knitters, and he’s about to work (again) with Los Straitjackets on a live DVD.

Linett hails from the genteel New York suburb of Scarsdale, where his early tech experience included creating psychedelic light shows for local bands and later running his own concert sound company called Nightshade and Dark. “We did a lot of things on the East Coast college circuit,” he says. “We worked with Livingston Taylor, Seals & Crofts, Sha Na Na — lots of bands. I did that for a few years.

“I first came out here [to L.A.] in about 1972 and worked at a number of small studios — a place called Artist Recording, which is long gone, and at Mystic, which was the former Delfi Studios — and got some basic studio experience, although they weren’t exactly great studios.

“I stayed in L.A. for two years,” he continues, “but eventually returned to New York, where I started working for Ed Chalpin, who’s best known as the guy who signed Hendrix to a $1 contract and ultimately made millions from that ‘investment.’ I worked at Chalpin’s studio for only a few months. They specialized in Top 40 soundalikes for the European market. After that, I went back to college at Boston University for a while, still knocking on doors trying to get jobs in recording.”

From left: Mark Linett, Brian Wilson and George Martin at Linett’s studio

Linett caught a major break when he got an emergency call to fill in for Frank Zappa’s tour mixer, who had fallen seriously ill before a show in Hartford, Conn. “I flew down on a little prop plane, got there between sets and was told to go out to the [board],” he remembers. “So I’m watching and suddenly the other guy just disappeared! He came back once for about 10 minutes and then was never seen again. So I mixed the rest of the show and they hired me on the spot. I worked for Frank for the next two years, mixing live and then running the P.A. During that time, I also toured with ELO [Electric Light Orchestra] as part of Zappa’s production company.”

After working “a big, long grueling” tour with Earth Wind & Fire and a brief (and more pleasant) stint with Journey, Linett finally made the transition back to studio work at L.A.’s Sunset Sound. “In those days, they had two second engineers for every studio because they constantly ran double shifts. Thanks to a recommendation from George Massenburg, when they opened Studio 3, they hired me and I ended up working there for about two years and managed to build up the clientele I was thirsting for. I worked with a lot of great engineers: Bill Schnee, Humberto Gatica and Don Landee. I worked with Hall & Oates, the Doobie Brothers, Jimmy Webb — there was a lot of pop coming through the studio in those days.” Nearly three decades later, Linett would cut Smile there.

After working as an independent for a while, Linett landed a job with Warner Bros. at Amigo Studios under veteran engineer Lee Herschberg. “That was a great place to work,” he says. “It had a DiMedio/API console in Studio A, and Studio E had a Harrison. We did the first two Los Lobos records, I worked with Michael McDonald, did Randy Newman’s Trouble in Paradise, I got to work with Eric Clapton and I also did several of Rickie Lee Jones’ records there. I was at Amigo until it closed in 1984, and then I stayed with Warners until 1985.”

I ask Linett what in his personality allowed him to work smoothly with artist-types like Jones, Zappa, Newman and, later, Wilson. “I don’t know,” he answers. “They’re all completely different. Rickie could be very demanding — she had high expectations of what she wanted from everybody — but we always got along great. Frank was always an extremely nice guy; even when he would let somebody go, he was never unpleasant. And Randy is so much fun to work with. I was a huge fan, so to work with Randy and [producers] Lenny [Waronker] and Russ [Titleman] was just about the most fun I ever had making a record, with the possible exception of working with Randy, Lenny, Steve Martin, Chevy Chase and Martin Short doing The Three Amigos soundtrack.” Linett also engineered some of Paul Simon’s Hearts and Bones for Waronker and Titleman during this period, and he also was the mix engineer on numerous Hendrix releases, including acclaimed live albums from the Monterey Pop Festival and Winterland.

Linett’s departure from Warners also coincided with the construction of a large studio in his home, and it is there that he has done much of his work during the past 15 years. “All of Brian’s projects have been recorded and/or mixed there, and probably 50 other albums,” he says. The studio, dubbed Your Place or Mine (Linett also has a mobile recording rig), features a highly customized API 2488 console; Pro Tools|HD2; 8, 16 and 24-track Studer 820s; and a wall of vintage outboard gear. One unique item that he often uses is the original Bill Putnam tube console from Western Recorders Studio 2, where Wilson made many of his records in the ’60s.

Linett’s initial connection to the Beach Boys actually came through some work he was doing with the band America. “I had done an album with America called A View From the Ground at Amigo [in 1982], and Carl Wilson sang on that. But the first Beach Boys music I did was the background session for David Lee Roth’s version of ‘California Girls,’ featuring Carl and Christopher Cross. Carl brought a cassette of the [Beach Boys] original and I remember him marveling at his brother’s handiwork. He told us that the Beach Boys didn’t do the arrangement like that anymore, and so he had to figure out the original parts.”

In 1987, another stroke of fate led to him hooking up with Wilson for the first time. “I called Ocean Way one afternoon to book time for a project, and the woman who was booking the studio said, ‘By the way, we just got a last-minute booking for Brian Wilson tomorrow in Studio One and we don’t have an engineer. Would you like to do it?’ So I did the session and ended up working on that album [Brian Wilson] for more than a year. The funny thing about that is I might have ended up working on the album anyway because Lenny and Russ were involved with it.”

A Beach Boys fan since his youth, Linett says that it was mainly through working with artists who had admired Wilson that he came to understand his genius as a producer. “Jimmy Webb and the guys in America were really into Brian,” he says. “I remember doing something on Jimmy’s album Angel Heart, a song called ‘In Cars,’ and very much trying to get a Pet Sounds feel, with timpanis and percussion and recording stuff out in the hall to get a live-er sound, because at that point, the rooms at Sunset weren’t live enough. But I didn’t have a real good idea how to get that Pet Sounds — type of sound.”

As he got into working on Wilson’s projects and Beach Boys reissues, and from talking to original Beach Boys engineer Chuck Britz, Linett learned much about how their classic albums were recorded — how the technology of the times shaped studio methodology. “I was talking to Lenny Waronker about this the other day,” Linett offers. “The reason why the Wrecking Crew [the famous group of first-call L.A. session players] worked all the time, aside from the fact that they were great musicians, is that the technology was such that you had to have people in the room who could play what needed to be played and get it right because you weren’t going to be able to fix it later. They were always in the same rooms with pretty much the same mics, and you knew you were going to get a track.

“Brian took it all to a higher level because of his incredible skills as a producer and arranger, but the basic idea was you put great players in a studio like Western 3 or Goldstar, without headphones in most cases, using the bleed between the mics to your advantage. That’s a huge part of what made the sound when you listen to the tracking dates. ‘Play softer, play louder, play this, let’s move that mic.’ Going for this overall locked thing as opposed to, ‘We want it to sound like something, but we still want to be able to replace the drums or turn off the bass or isolate the kick.’ When you’re only going to 3-track, it doesn’t matter if the kick drum mic is picking up the bass; that’s not the point. The hardest thing for people to realize is that when you had a bass, particularly an acoustic bass, you’d have it positioned next to the drum and you’d mike the bass first and it would pick up a lot of drums, but that would just mean that you would fill in the drum mics accordingly. It wasn’t like it is now, where you start with the drums and put everything around it. Everything interacted, so it was more about creating an overall sound organically.

“A lot of people think all those records Brian made in the ’60s were recorded in huge rooms to get that big sound, but the opposite is actually true. You had to make them in a small room where the reflections that you were picking up on adjacent mics would be useful and then, of course, you added all that great reverb. If you tried to do that with a small band in a big room, what you got bouncing off the walls was garbage. And it was all done on 3-track!

“But when 8-track and then 16- and 24-track came along, people realized, ‘Hey, we can isolate and replace.’ Then people went in booths, the studio got dead, the headphones came out, the playing changed. Up to that point, even rock records were largely captured performances with overdubs, perhaps, but it was still about musicians playing in the studio and getting a sound and a vibe. The studios got deader because you didn’t want that ‘good’ bleed anymore. Then, of course, people made different kinds of records. They’re valid, good records, but it’s a different aesthetic, in a way. There were some great records made in those kinds of rooms. But the music changed to fit the technology. Now, more recently, I think the pendulum has swung back the other way.”

Which brings us, inevitably, back to Smile. “We decided early on that we would try to record it in a manner that fit what Brian was doing 40 years ago. We wanted it to sound like it sounded then, so let’s try to do it the way he did it then. And with the exception of using some sampled keyboards, we did it almost exactly the way Brian worked in 1966. We cut the tracks at Sunset Sound in Studio 1, where some of ‘Good Vibrations’ and ‘Heroes and Villains’ had been recorded. We recorded it with everyone playing live, including the string and horn players. We used high-res Pro Tools, 88.2 kHz, Apogee converters front and back. Sunset has highly custom boards in there with the API EQs. We did a few overdubs — we added acoustic bass and all the vocals and mixed at my studio. But I’m very proud to say that the tracks really do have a lot of the signature sound and vibe that Brian got in the ’60s.

“The irony is that what Brian was trying to do with Smile, as he did with ‘Good Vibrations,’ is record in a modular fashion: ‘I don’t have to do a whole song; I can do a verse and then a chorus and then the bridge, and I can either know how those are going to fit together,’ or — as he did with ‘Good Vibrations’ and endlessly with ‘Heroes and Villains’ — ‘I can shuffle this around until I’m satisfied that this order works.’ The problem is that in 1966, that meant cutting tapes and making copies. With the advent of the workstation — that’s what let him put all the songs together in a manner that was acceptable to him because you could try things so quickly.”

Wilson’s Smile, brought to you by Digidesign? Linett laughs. “To a certain extent that’s true. It could’ve been finished 40 years ago, but you could also say it was a record that was dying to employ random-access editing.

“The completion of Smile was an enormous positive experience for Brian,” Linett says. “It was amazing when we were mixing this — and we didn’t burden Brian with being here hour after hour while Brian’s musical director, Darien Sahanaja, and I got the mixes together. He would come in and listen to large sections and make comments and changes. So at the end, I gave him a CD ref and said, ‘You know, Brian. That’s Smile!’ And when he realized that, you could see it on his face what a relief it was and how much satisfaction it gave him to have been able to complete his masterpiece after almost 40 years. From that point on, he’s been a different person. It was an enormous healing process for him.”

Cut back to the present, and there is plenty of work for Linett that doesn’t require any musical archaeology or glimpses of the past. He raves about Alvin’s recent studio album, Ashgrove, and an album Alvin produced for singer and fiddle player Amy Farris. And then there was the Peppers: “One interesting thing about the project is it was all done analog,” he says of the tracking. “We ended up cutting something like 37 songs. The biggest problem was finding enough 2-inch tape after Quantegy went bankrupt. That and doing 2-inch tape edits. Just like the old days!”

New day, different challenges.

Click here to read Blair Jackson’s feature on the Beach Boys’ masterpiece Pet Sounds, mixed in surround by Mark Linett.

Linett also engineered Wilson’s Live at the Roxy double-disc. Click here to read about the process.