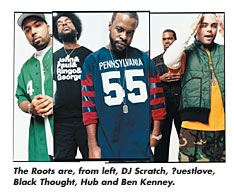

As one of the few actual performing groups in hip hop, The Rootshave been enormously influential and successful during their 12 yearson the scene. Not only do they break the mold by actually playinginstruments rather than relying on tapes, but they have alsodemonstrated a flair for the experimental: taking part in adventurouscrossover collaborations and not limiting themselves to any particulargenre, but thriving because of their sonic diversity.

However, success did not come early or easily for thePhiladelphia-based group, which was strongly influenced by thepioneering use of live instrumentation in hip hop by Pharcyde and theBrand New Heavies. Initially, founding members Ahmir Khalib“?uestlove” Thompson, an extraordinary drummer, andvocalist/rapper Black Thought (Tariq Trotter) didn’t even have themoney for standard rap/hip hop gear, such as a sound system, turntablesand microphones. So they formed a real band, adding bassist Leonard(“Hub) Hubbard and rapper Malik B. The present lineup alsoincludes keyboardist Kamel Gray, DJ Scratch, guitarist Ben Kenney andhuman beatbox, Rahzel. Their first four albums drew critical acclaimand respect from peers, but sales were not stellar and, during thatperiod, The Roots were thought of primarily as an underground act.

Their 2000 release, Things Fall Apart, dramatically changedthat preconception. The CD went Platinum, and for the past two years,the band has vitually lived on the road, with minute blocks of freetime in between marathon tours. It’s a testament to their eclecticismand diverse following that they’ve toured with the likes of DaveMatthews, Nelly Furtado, Jay-Z, Musiq, Jill Scott and Moby, to name afew. On the other hand, the heavy schedule of appearances, along withthe demands of individual side projects, has afforded them little timeto record Phrenology, the much-anticipated follow-up to theirbreakout album.

“It was about us being meticulous,” stresses Thompsonduring a soundcheck at the House of Blues in Anaheim, Calif. Thebackstage area at the club is filled with a discordant mix of musicianstuning up and trams for the Disneyland concourse whizzing by.“The song ‘Rolling With Heat’ took about nine daysfor me to get the drums right. Every note and cranny on that record wasthought out, even the maracas on ‘Quills.’”

Thompson doesn’t consider himself just a musician, producer andengineer, but rather a sound designer. He is also something of a musichistorian, with a mind-boggling collection of more than 30,000 recordson vinyl alone. In conversation, he cites a variety of discs —from landmark to esoteric — as influences and references withwhich to navigate The Roots’ musical philosophy. “Prince’s DirtyMinds had eight songs; Thriller by Michael Jackson, 10songs; and Innervisions by Stevie Wonder was only eight or ninesongs,” he notes. “It hit me that every classic record isabout a half-hour or 33 minutes at the most. That’s not even songnumber five on my records. Here we are bashing ourselves over theheads, trying to balance these gargantuan 16-song statements. So in thebeginning [of Phrenology], our statement as a group was going tobe a simple record, but not in the center. It’s definitely left[experimentation] and right [pop mainstream]. Our interpretation ofright is the Nelly Furtado song ‘Sacrifice,’ which is stillunlike anything on radio today.

“Basically, we wanted to appeal to the public and sort of pushthe envelope, too,” he continues. “We felt we had anaudience waiting for the next move, and instead of offering them whatthey expected, we sort of sucker-punched them. You don’t want to be toooverambitious and be accused of being pretentious and too artsy. Thenagain, you’re expected to make a statement. But the one you make,you’re not sure the world is ready for.”

After years of working at Sigma Sound in Philadelphia, where theywere tutored by legendary engineer Joe Tarsia and others, The Rootshave gone in a different direction with Phrenology. It wasprimarily mixed by Bob Power (Sony Music Studios, N.Y.) and RussElevado (Electric Lady, New York City): “The two greatest sets ofhands and ears ever to mix music,” Thompson crows, “anddoing the most progressive work in black music in the ’90s andbeyond.” Additionally, Jon Smeltz did much of the originaltracking and preliminary mixing at The Studio in Philadelphia.

Smeltz and Power have worked with the group often through the yearsand have encouraged their sometimes unorthodox methods. Elevado, on theother hand, became acquainted with Thompson through projects that thedrummer produced for Common, Erykah Badu and D’Angelo. “He’s onemore key element that wasn’t in the past five records,” Thompsonsays. “He works in another place that’s very anal about keepingstock of their recording equipment. He introduced us to Eddie Kramer,who was Jimi Hendrix’s recording engineer [Hendrix was a majorinfluence on The Roots], and from him, we got a lot of stories, methodsof mixing and recording techniques.”

Those pearls of wisdom resonated with Thompson, who admits that he’sobsessed with every nuance of engineering that goes into a Rootsrecord. It even helped him warm up to Pro Tools, which he’d previouslyavoided. His change of heart came about when he was at Electric Ladyand got into a conversation with Lenny Kravitz. Thompson recalls,“Lenny told me, ‘Hey, man, I got tired of keeping up withthe analog game. I’m totally digital.’ I said,‘What?!’ He said, ‘Dude, if Jimi Hendrix were alivetoday, he’d be using Pro Tools.’ I said, ‘That’s a lie andyou know it!’ So a couple of weeks later, I was talking withKramer while he was working on the Jimi Hendrix BBC Live album.I said, ‘Isn’t that funny what Lenny said about Hendrix and ProTools?’ He paused for a second and said, ‘Yeah, I could seethat.’ Then he went on to tell me that the classic Hendrixrecordings amounted to three engineers being human ProTools.”

Nevertheless, Elevado remains a staunch analog advocate. At ElectricLady, he has a wealth of vintage equipment in tip-top condition to callupon and he only uses Pro Tools sparingly. For his part, Thompson likesthe sound of analog and loves to experiment with old equipment.

“Often, artists will mix a whole album and then they’ll say,‘I have these five songs for you,’” Elevado says.“Those usually are the artsy ones, which I can really getcreative with. [Clients] will tell me, ‘Just do whatever youwant, and if you hear something, go for it.’ That plays a bigpart in the relationship I have with Ahmir. He looks for me to push theenvelope.”

At Electric Lady, Elevado worked on an SSL 9K console — hisfavorite — along with a wide assortment of analog outboardeffects, including Mutron Biphase, various flanges and envelopefilters, Leslie cabinets, MXR phasers, Neve 1081 and 1093 EQs, Heliosmic preamps, Fairchild compressors and gates. “People don’trealize how big a difference analog can make over digital,”Elevado says. “It’s definitely in the mixing process, because I’mgoing through all kinds of old tube compressors and EQs. That’s a hugepart of my sound.”

Bob Power, by contrast, likes to blend the old with the new,employing Logic Audio and Pro Tools TDM for recording and then mixingon an SSL 9000 J, but also favoring occasional enhancements from olderNeve outboard equipment. “It’s really nice to have MIDI and audioin one place, and with the TDM running, I’m afforded a lot of things Iwouldn’t ordinarily be able to do,” he says.

The veteran engineer/producer has been regularly relied upon by TheRoots to mix their more straightforward tracks and singles. “Theyuse me for what I’m good at, and working with them is different thananyone else,” he notes, “primarily because their musicsynthesizes so many different styles.

“For example, having a strong jazzy element in the chordchanges over a really nasty hip hop beat. From a mix standpoint, thecombination of elements they happen to use, which are all part ofmodern soul but normally not in the same song, makes it verychallenging. Fortunately, all of the stuff they brought in [analog anddigital source material], particularly for this last project, wasrecorded really well. Jon Smeltz did a lot of it. He’s a real seriouspro, and the stuff he records sounds great.”

Smeltz works mainly out of The Studio, a facility he and arrangerJohn Gold founded about seven years ago. The Philadelphia studiofeatures two SSL rooms; most of their work with The Roots was done inthe room with E Series board using George Augspurger mains. Initialtracking was done on a Studer 827 2-inch analog deck. In the laterstages of the sessions, during the second year, everything was recordedon Pro Tools.

“I’ve been recording music for over 20-something years,”states Smeltz from his home in Philadelphia. “I’ve worked witheveryone from Whitney to Mariah, and I guess I just learned from thevery beginning of my career how to mike live instruments. I used to bea [Sennheiser] 421 guy on the kick drums,” Thompson notes,“but shifted to the D-112 when it came out. Everything has justevolved, and I was even around when the RE-20 ruled for the kick drums.But with hip hop music and such, I always find that the 47 always givesme a nice solid bottom that I roll the top off of. Sometimes, I’ll eventake a Moogerfooger as a stand-alone unit, not the plug-in, which is anice way to shape the bottom. Often, I’ll print that on a separatetrack. Believe it or not, the drums were done after the fact, 80 to 90percent of the time.

“I’m about the sound and feel of the CD, that’s all I careabout at the end of the day,” he concludes. “People don’trecognize The Roots for having what I feel are some of thebest-engineered hip hop albums around. But then again, I’m the kind ofcat that cares about that type of stuff.”