From a distance, the trajectory of Steve Earle’s career follows a perverse but unbreakable logic: Everywhere he should have zigged, he zagged. Every time he should have said “No,” he said “Why not?” A lifetime of defying conventional wisdom has exacted its price, but Earle today finds himself in the last place he ever expected to be-in complete control. He owns the label that releases his records. He owns the studio where the records are made.

More important, he has control of himself.

Earle left his home state of Texas for Nashville as a teenager in the early ’70s, just as “outlaw” country singers like Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and Jerry Jeff Walker were abandoning the Nashville music establishment to become superstars back in Texas. The baby-faced Earle was perhaps the rowdiest outlaw of them all, a self-described “pinko” with a thirst for the wild life and a penchant for fighting cops. Yet he settled in on staid Music Row, which at the time was at the height of its countrypolitan kick.

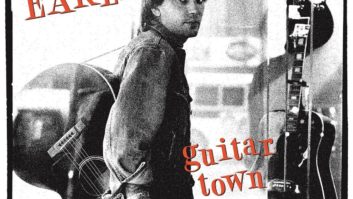

With his second album, Guitar Town (1986), Earle proved himself to be a first-rate songwriter, a master of literate storytelling in the manner of Tom T. Hall who could also flat-out get after it. Chafing against the restrictive label of “country” musician, Earle kept pushing out, edging closer to rock ‘n’ roll. In 1988, Copperhead Road became the first Earle record to catch on with a rock audience, and suddenly his name was being mentioned in the same breath with Bruce Springsteen and John Mellencamp.

But by the time Copperhead Road hit, Earle was already in the grip of a heroin habit that would eventually become all-consuming. After several lost years during which he gave up music completely, his free-fall ended in the only place it could have besides the morgue: Earle went to jail, on a misdemeanor for narcotics possession.

And that would have been it-more fodder for a “Where Are They Now?” feature-except Earle once again did the unexpected and began rewriting the script of his life. The long road back began with a brace of raw, acoustic songs on an album called Train a Comin’. That was quickly followed by I Feel Alright, whose self-referential title gave Earle fans the news they had been hoping to hear for years. His name began to crop up elsewhere, too. The searing folk ballad “Ellis Unit One” stole the show on the star-studded Dead Man Walking soundtrack. And his rueful “Goodbye” was a highlight of Emmylou Harris’s landmark Wrecking Ball album.

Then, with the 1997 release of El Corazon, Steve Earle stepped boldly to the front of the alternative country revolution. The record is a stunning smorgasbord of American music, from folk to pop to bluegrass to grunge. It ambitiously redrew the boundaries of what “country music” could be and earned Earle a Grammy nomination (in the category of Best Contemporary Folk Album).

But anyone who expected Earle to burnish his growing legend as the godfather of alt-country should have known better. Instead, he followed up El Corazon with this year’s The Mountain, an all-acoustic, all-bluegrass album recorded with the Del McCoury Band. Though some bluegrass purists may disdain The Mountain for its garage-band sound, the record has found an audience, and critics have been inventing new adjectives to describe its majestic mayhem.

Earle is not bashful about what he set out to accomplish with The Mountain. “My primary motive in writing these songs was both selfish and ambitious,” he writes in the liner notes, “immortality.”

Mix caught up with Earle in the Music Row headquarters of his label, E-Squared, to talk about the many twists and turns of his career, and his surprising (to him) development as a producer and record executive.

We’ll start with the question you probably hear every time you go back to Texas: How did you wind up settling in Nashville?

Well, let’s see. I was 19 years old, and I’d been hitchhiking around in circles in Texas for years, playing all the same places. The whole Cosmic Cowboy thing was going on in Austin, and that was kinda cool. Capitol Records came through there and signed a bunch of acts, Willie Nelson moved back and Jerry Jeff Walker was on MCA at the time and selling a lot of records and playing small arenas in the Southwest. Everybody was telling me, “This is it, you should stay here.” But most of the people who were telling me that were refugees who had been to New York and had been to Nashville and had been to L.A., and I was 19 and I hadn’t been there yet. Austin wasn’t far enough away from home-it was only 90 miles. And also, I got there and looked around, and the weather was too good, the girls were too pretty and the dope was too cheap. I knew I’d never get anything done in a place like that. So I came to Nashville.

Nashville girls aren’t going to be too happy to read that they run second to Austin.

Aw, the girls in Nashville are nice, but have you ever been to Austin? [Laughs] The girls in Nashville are all right. I married about half of them.

You’ve been recording there a long time now. What rooms do you like best?

My favorite room in this town is probably Woodland, which is over in East Nashville. It’s been there since the ’70s. There’s two kinda medium-sized rooms and a small mix overdubber in there. The room I like is the old one in the back. I love that place. I’ve never made a record there, but I’ve worked on a lot of records there. I’ve produced a couple there, and I did Wrecking Ball there, which I played on about half of. The room I’d most like to own in town is the old Monument Studios, which I think is Masterlink Studios now. I’ve always wanted to buy that room.

Why?

I like recording studios that look and feel like recording studios, instead of spas or whorehouses. I don’t know why. I guess I’m just sort of lazy by nature, and when I’m working I like to know I’m at work. I don’t like a lot of distractions. I like a lot of wires.

So the technical part of making records doesn’t intimidate you, then.

I’m really sort of new to caring about the recording process itself. I mean, I had home studios, but they were just for demo purposes. And I made digital records for a long time, simply because I started making records for MCA in the mid-80s, and that was a rule. Jimmy Bowen owned every X-series Mitsubishi in town and he leased them out. So if you recorded for MCA, you recorded digitally. But in the ’80s and up through the early ’90s, when I kinda quit making records because my drug habit got out of hand, I didn’t care that much about the recording process. I didn’t know any better and I just didn’t have a dog in that fight.

Then I went to jail. And when I got out and made Train a Comin’ which is really the first analog record I ever made, it was like it opened up this whole world. One day I went over to Ray Kennedy, who had moved his home studio into what was the B studio of the old Digital Recording. I went there when I first started writing songs for I Feel Alright and did a guitar-voice demo for “I Feel Alright” and that ended up being [the title track]. We overdubbed bass and drums, and the next thing I know I’m producing a record. All of a sudden I found myself going out with Ray and finding and buying stuff like 1176s. We’re way into 1176s. That’s our deal. Our sound is no reverb and a stack-we’ve got on ten 1176LMs and four 1176s. The blue label ones, which are the pre-LM ones, are a little nastier-sounding, and for certain things, like my voice, that’s what we always use. It just likes my voice. And old Telefunken mic pre’s. And V76s. Originally we had three V76s that came out of Abbey Road that Ray owned when I got into the studio.

Then, after I Feel Alright, when we started this whole series of records that Ray and I made together for E-Squared, our accountants decided that we needed to be partners in a studio. So we formed two companies. One was Room and Board itself, and the other is twangtrust, which is our production company. And actually my brother [Patrick Earle] is sort of an associate member in that partnership, too. He’s our second engineer and works with us whenever we do stuff for films. And whenever we just track something, my brother plays drums. He’s a pretty good little punk rock drummer.

What we’ve done is come up with this creative environment that’s perfect for me. And a lot of other people like it, too. Between Ray and me, we own about 170 guitars, and they’re all hanging on wall hangers in the studio where we can see them, so nearly all of them get used. And we have a collection of about 35 or 40 really great amps, and they’re just stacked up on one wall. Most of them already got power to them, so all you have to do is walk up and plug into them. If it doesn’t work, pull out and plug into another one. It’s a studio in the real sense of the word-it’s a place to make music. We’ve got a lot of weird drums. We’ve got a great collection of snare drums, a good harmonium. I brought back a couple of really weird little percussion instruments from Vietnam. We’ve got a hurdy-gurdy player on call.

It’s real, live, organic, experimental recording, and it’s really just based on the idea that nothing’s been done to improve the way recording sounds since 1963 or ’64. Everything since then has been about adding tracks. Or, once they got into big multitrack machines, noise reduction. And then cost reduction. But nothing sounds better than a V76, and there’s nothing better to mix to than a good half-inch 2-track. It’s real simple. Like a lot of people nowadays, the yardstick for us is Beatles records and records that were made in Europe during that period. The early Rolling Stones records, and middle period stuff like “Ruby Tuesday” and stuff like that. No one’s really done anything that made a guitar or a drum sound better coming back off a tape since then. I don’t hear it, anyway. I like to say that we’re low-tech, but we’re not low-fi.

You first got together with Del McCoury for just one song on El Corazon-“I Still Carry You Around.” How did that evolve into a full-blown bluegrass album?

Bluegrass is something that has always been a huge component of what I do. But I finally got good enough that I got the balls to actually try to play it. Albums sort of have a life of their own. Once I get three or four songs written, I’ve done it enough now that I start seeing someplace that they’re going. The deal with El Corazon was I was ready to try to do everything I knew how to do on one record. And I had this perverse thing where I loved the idea of making what was essentially a rock record and sticking a bluegrass track in the middle of it. ‘Cause I think bluegrass is rock ‘n’ roll. Carl Perkins said, “Hey, we were just trying to play like [Bill] Monroe, but we didn’t play mandolin.” It’s the original alternative country music. Or at least the best of it is.

“I Still Carry You Around” was my first attempt at writing something specifically bluegrass. Ronnie [McCoury] and I had gotten friendly; he’d played on a couple of tracks on my records and a couple of records I produced such as the V-Roys, and that’s sort of what started it. Del himself was vaguely familiar with me. He knew about Copperhead Road and Guitar Town.

Anyway, after we recorded “I Still Carry You Around,” I played with the band at this thing that No Depression sponsored and we had to rehearse a set for that. And that’s the first time I worked on one mic with them live. When we got done, I was just so proud of myself, because I hadn’t put Del’s eye out. After the gig, I went back to him and said, “If I was to write a whole record of bluegrass songs, would you guys record it with me?” Del said, “Yeah!” I read an interview with him later where he said he thought it would be four or five years from now or something. Nine months later, I had 12 songs and we were in the studio. He just didn’t know me well enough to know that I don’t fool around.

The sound of the songs on The Mountain is so much thicker, more rock than “I Still Carry You Around,” which has a more traditional bluegrass sound to it.

I’ll tell you what it is. When we did “I Still Carry You Around,” Ray and I still only owned three V76s. But since then we purchased an old Telefunken sidecar, a broadcast sidecar, with eight channels. So we now have 12 channels. And because of the bluegrass thing, there was just a small number of mics and it was all live. We were able to record the entire record through the top of the 1963 Telefunken straight to tape. We didn’t even use the CAD console. Every single instrument is going through a V76.

You love to collaborate with other musicians. Is it the same for you in the studio? Do you consider yourself a collaborator with Ray and the other people who work with you in the booth?

Yeah, without a doubt. Ray and I produce records together, but he also records on his own. I can’t do records without him, but he can do records without me, because Ray’s not just an engineer, he’s a guitar player and he made really good records for Atlantic as a country singer. He had hits. But he just got tired of it, dealing with the changes that have come about in the country music industry. He didn’t want to play that game.

I’ve been avoiding asking you about the state of country music. It seems like too easy a target.

Ah, well, you know. I don’t even know that much about it. I couldn’t name you three people that are on the country charts right now. I do not really care. For a long time it’s been the new MOR. That’s exactly what it is. There’s nothing wrong with making pop records and marketing to a certain demographic. I have no problem with that. Music doesn’t have to be profound. I just think it’s really important that it doesn’t go out of its way not to be. [Laughs] All music has a place, except for maybe Garth Brooks records. I think he’s the anti-Hank and needs to be done away with somehow.

Horsewhipped, something like that?

I’ll throw on my cowboy boots again when Garth Brooks goes back to Oklahoma.

I’ve talked to people who have said that Nashville has really changed in the ’90s, that there’s been a big migration of talent there and that the recording environment is very different from what it was in the ’70s when you first got there. What are the changes that you’ve perceived?

I’m not sure that I agree with that. It’s true that we get a lot of people coming here. I don’t know that it has changed anything, though. There’s always been music to the left of center made here. And there’s always been rock music made here. Bob Dylan used to come here to record. Roy Orbison made records here. When I got here in the ’70s it was me, Guy Clark, John Hiatt…

There was a circle of people that weren’t writing stuff for mainstream country radio. And that’s sort of always gone on. My partner in this label, Jack Emerson, managed Jason & The Scorchers and got them their first record deal, and he sort of started alternative rock in this town. There’s always that stuff going on. It’s just that sometimes people pay attention to it and sometimes they don’t.

Nashville is a nice place to live. People, when their kids start getting to a certain age, start wanting to live here as opposed to trying to raise their kids in L.A. That’s why Emmy moved here. Look, it’s a city with big-time music business infrastructure that’s cheaper to live in than L.A. or New York, and it’s a really, really pretty state. And if you can put up with a lot of Baptists, then it’s a good place to live.

You mentioned Emmylou Harris. I know you really enjoyed playing on Wrecking Ball, and she’s on just about every record you’ve made. What’s it like recording with her?

Playing on Wrecking Ball was such a privilege for me. I was really honored, and it was great how it was done-very organically. Emmy’s like…

God, if Emmy ever moved out of Nashville, that would be the first time I would ever consider leaving. She’s so much to me. There’s me, her, Buddy and Julie Miller, who are a cottage industry unto themselves, and a handful of people here who are this peer group that I have that are just really amazing. If Emmy’s around, she’s on anything I do at some point, and it’s just always a joy. I’ll do pretty close to anything for Emmylou Harris. I’d do anything short of start shooting dope again for Emmylou. That’s about the only thing I wouldn’t do.

Do you think you’ll ever do a full album with her?

Oh, God, I’d love to. But you know, there’s a lot of stuff left to do. That would definitely be one of them. I want to do a whole record of Townes Van Zandt songs one of these days. I’m seriously thinking about it. I’m capable of playing exactly like Townes did. I think I want it to be really straight interpretations of the way he performed his songs.

You said you’re going back into the studio for a new album in September. Do you have ideas yet of what that record will be like?

It’s three-quarters written already. It’ll be 100 percent written by the time we start recording. It’s a rock record, a pop record, or whatever. I mean, it’s going to be more like El Corazon, kinda all over the place. A loud songwriter record.

How is it different producing the bands on your label than producing one of your own records?

I make records relatively quickly, but with the baby bands I do a lot of pre-production in their rehearsal space, where they’re comfortable, before I bring them into the studio. Especially if they’ve never made a record before. My stuff is actually recorded in the time between other records, up to a certain point, then it will sort of reach critical mass and we’ll go in, cut the tracks and finish it.

My favorite thing is making a record on a kid that’s never made a record before. You have no idea how cool that is. I learn a lot. I steal unmercifully from these kids that record for my label; it keeps my music fresh. I insist on just a couple of things. I insist that it be fun. I’m not opposed to someone who wants to put their hairshirt on to make records, I just don’t want to do it myself.

I read somewhere that you consider yourself a writer first and foremost. What does that mean in terms of how you go about crafting your songs?

I’m a lot better musician and a lot better producer than I thought I would ever grow up to be, but my gift is still primarily literary. In fact, I write short stories now; I have for the last few years. I’m getting ready to publish a collection. And I write poetry, which I just started recently. That’s the hardest thing in the world. I write albums to be albums. I always have, and I’ve gotten better and better at it, I think. I’m having the most fun doing it that I ever have.

I write all the time. Every day. I mean, I write poetry, or I write short stories, or I write songs every single day. And I have ever since I got out of jail. I was almost dead four-and-a-half years ago, man. [Laughs] And I didn’t write a song for four years, the last four years I was using.

You didn’t write a song for four years?

Nope. And it almost killed me.

So then writing every day is how you stay connected, how you keep it together?

Well, I feel like I have a gift. I’ve finally accepted that, and when one has a gift you are supposed to use it, and when you don’t use it, bad shit happens to you. That’s what I firmly believe. But I stay clean the same way everyone I know stays clean. I go to meetings and I have a sponsor and I do it by the book. It’s the one area of my life where I actually listen to somebody else. But, yeah. I survived three wrecks that should’ve killed me, one overdose that should’ve killed me. I mean, I’m real lucky to be here and I just don’t f- around anymore. I don’t think I’m immortal anymore. I’ve sort of stepped up the level of the way I do everything.

“Steve and Ray [Kennedy] hadn’t really worked with a bluegrass band before, so I helped out with some of the arrangements, picking musicians, things like that. They have one of the most amazing studios in this town. We walked in and there were mics standing everywhere in this one big room. Old mics, new mics. No isolation, no baffles. Steve was on one side of the room with his guitar where he could make eye contact with us, and we stood grouped together on the other side. We ran the tunes down just to see who did what, then Ray pressed the Record button and off we went.

“It’s a totally live record, except for some vocal overdubs, I think. These guys compress everything and burn it on the tape really hot. It’s real, live music, and that’s what I love to do. It may have some warts on it, but with all of us playing close together there was no way to get separation, so there was no way to dub even if we wanted to. The way they do it is like nobody else; it’s more like rock recording than anything. They must have over a hundred guitars up on the walls in the studio, and when we started playing, of course, they all started ringing out. It was just this big, ringing noise in the room. It was the most incredible sound.”

“You want to get a real voice on tape, so that it gets on tape as good as possible. We don’t do a lot of post-production, because for us the performance is what we’re after. A lot of it is picking the right gear, then encouraging people to sing really up close to the mic. You know how some people say that you need to get at least six inches away from the mic in order for the sound to fully develop? That’s a bunch of crap. Get it right up in their face, get that capsule right down the larynx, so it gets everything. It’s a little harder on the mics to do that, which is why a lot of engineers won’t do it. They don’t want to wear out their $10,000 antique mics, which is totally understandable. But that’s where the character of the voice comes from.

“For Iris DeMent [who sang with Steve Earle on the duet “I’m Still in Love With You”], I put one mic up for her that sounded too tinny. So I tried another, a German bottle mic from the mid-’50s [Neumann/Gefell CMV563] that had the capsule on the outside and it was perfect. A lot of people have told her that that’s the best her voice has ever sounded on record. I kinda got lucky with her, because sometimes you can go through a dozen mics trying to find just the right one.”