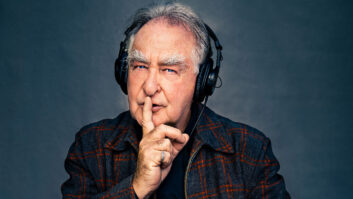

From left: engineers Matt Cohen and Eric “E.T.” Thorngren, and producer Jerry Harrison

photo: Sasha Gulish

Somehow, it makes perfect sense that Talking Heads — one of the most inventive, forward-looking and influential bands of the modern rock era — would be among the vanguard of groups to truly embrace surround sound technology. Early this month, Rhino will release the eight studio albums in the Heads’ catalog in a box set of DualDisc hybrid CDs, called Brick. One side contains a DVD-A surround mix and the original stereo mix, and the other side the stereo version plus bonus tracks (playable in a conventional CD player).

Former Heads keyboardist/guitarist/singer/arranger Jerry Harrison, a very successful producer for many years (Live, Crash Test Dummies, No Doubt, the Von Bondies), was at the helm of the elaborate 5.1 mixing project, so it was clear the project was in good hands. Ace engineer Eric “E.T.” Thorngren, who had been at the board for two of those Heads albums — Little Creatures and True Stories — was the chief engineer on the remixes, ably aided by Matt Cohen, who has been working with Harrison for the past few years. The mixes were done at Harrison’s cozy Sausalito Sound studio, just steps away from the San Francisco Bay and with a wonderful view of Mt. Tamalpais from the deck off Cohen’s upstairs work room. It’s a really nice place to work.

And when I go over to “The Toe,” as Thorngren and company have taken to calling it, on a beautiful, sunny day in March of 2004 to hear some early mixes, it couldn’t seem more inviting. Shut the door, sit in the sweet spot and I’m enveloped by one amazing Talking Heads tune after another, the Blue Sky monitors pumping at “11.” You’ve never heard “Burning Down the House” (from Speaking in Tongues) quite like this: the front line rocking hard, with drums and bass kicking their way out of the center, vocals cascading out of the front and rears, keyboards dancing beside me left and right. Wow, this is what it’s all about! In surround, “The Overload” (from Remain in Light) sounds like some swirling, moderne Pink Floyd track, but feels completely new.

At that point, more than a year ago, the plan was to release just two Talking Heads albums in 5.1 and see how the market responded. “It actually began when we were putting together the deal to do the Greatest Hits album with Rhino,” Harrison says. “I brought up, ‘Well, if we’re going to be doing reissues, shouldn’t we be doing surround mixes, too?’ Rhino was into it, and we identified these two records — Remain in Light and Speaking in Tongues — as being the most appropriate to begin with.”

Fortunately, the tapes were in pretty good shape. Once they had been baked, the tapes were taken over to Penguin Recording in Pasadena, Calif., to be transferred by John Strother to Pro Tools at 192 kHz, “but when we brought it up here to mix,” Thorngren notes, “we reduced it to 96 because Pro Tools works better at 96 — you get more tracks and can use more plug-ins. We also did a listening test, and with that many channels of material, the difference between 96 and 192 was negligible.” Sausalito Sound is equipped with a Pro Tools|HD 6.2.3 workstation, a 32-fader ProControl, scads of plug-ins, three Dangerous Audio 2-bus units and rack after rack of classic and modern outboard gear: Neve, Telefunken and Daking preamps; Universal Audio compressors; and much more. Everything is easily accessible, “set up almost like a Pro Tools plug-in; there’s no patching needed,” Thorngren says. “So I can say, ‘Let me hear the 1176 on the bass. No, that’s not right. How about the Distressor or the Neve?’ And it’s really easy.”

However, before mixing began, there was the small matter of figuring out just what the hell was on the tapes. Track documentation was spotty and often confusing. “We’d put up the stereo mix of the finished record and study it,” Thorngren says. “Then I’d sit there and figure out who played what when. They might be marked ‘Prophet 1,’ ‘Prophet 2,’ ‘Prophet line,’ ‘Prophet solo,’ and on each track, there’s all this stuff going on. Sometimes a whole track would play and it would just have two little blips on there. I was also concerned with which instruments would have reverb, what type of reverb, the sound of it, the timbre, the length. It was poorly documented.”

Cohen adds, “There might be a bass drum for half the track and then it might be guitar for half the track. And then there would be whole tracks of guitar or keyboard that weren’t used at all for whatever reason. On ‘The Great Curve’ [on Remain in Light], there were so many sweet lead lines that were not part of the finished recording.” “We called it forensic mixing,” Harrison adds. “Typically, it would take a day per song just to figure out what was on there.”

Once the tracks were sorted out, the greatest challenge in doing the surround mix was “trying to maintain the integrity of the original mixes,” Thorngren says. “You want it to sound like the original album as much as possible, but with more dimension, more detail.” Even accomplishing that has its pitfalls, as the team learned. “We’d put something in the back [speakers] and think, ‘Jeez, that’s really distracting,’” Thorngren says. “And then we’d try moving something around, and a lot of times, that wouldn’t work either.”

“We’d have a guitar part up front and think, ‘Let’s move it to the back during the chorus,’” Harrison adds, “but then it would sound artificial and the front sounded too empty.”

“Eventually, we found the right balance of what felt right,” Thorngren says.

Their final approach to mixing the band was fairly consistent and straight-forward: Chris Frantz’s drums and Tina Weymouth’s bass anchored the middle; David Byrne’s lead vocal and his always interesting rhythm guitar parts were up front. Thorngren notes, “I set up left and right as our buses for a phantom center and then took a determined center send off of that channel at -6 dB. So you can go to the center, and if you shut everything off, you’d have a pretty good drums and bass and lead vocal and parts of the guitars, but you can also shut it off and still get the whole experience. Then, things that were not part of basic rhythm section might fall toward the outsides and the rears.”

That doesn’t mean that Harrison’s keys and various vocal backups were placed exclusively in the rear, but that is where some of the music’s more ornamental aspects fell, as did various reverb shadows and some effects. A few songs have some movement across the rears, but it’s mostly quite subtle. “On Remain in Light,” Thorngren says, “there were all sorts of sustain-y things and it’s really nice to move them. Sometimes we’d find that if you moved things really slowly, you wouldn’t really notice it unless you were really listening to that thing, but it created a nice effect.”

“It was important for the music to feel ‘whole,’ and if it gets too spread out or there are too many tricks, it stops feeling like the same performance [as the original mix],” Harrison adds. “Before we started, we did a survey of other surround mixes and we found that a lot of them that sounded pretty good on first listen weren’t as exciting as the original because you didn’t hear it as a whole — you were conscious of how it had been spread out — and the song didn’t have as much emotional impact.”

Along the way, the trio employed a slew of tools to optimize the sound, from the Digidesign DNR noise-reduction plug-in used to clean up dirty tracks to Roland’s Dimension D chorus, “which added a really nice, subtle color,” Harrison says.

Once Remain in Light and Speaking in Tongues were completed in the late spring of 2004, Byrne popped out for a visit and was extremely impressed, and then the brass at Rhino flipped for the mixes and decided to turn Harrison, Thorngren and Cohen loose on the rest of the Heads’ catalog, which explains how work on the project stretched out for another year (interspersed with other projects they were involved in, together and separately).

When I return to Sausalito Sound in mid-summer 2005, the project is in the can and the team is eager to play me more mixes. Once again, the results are extremely impressive. I rattle off some of my favorite Talking Heads tunes: The big choral opening of “Road to Nowhere” (from Little Creatures) sounds like it’s ringing through the vaults of some gothic cathedral; and guitar lines and percussion skitter across the rears on Naked‘s wonderful slice of Africana, “(Nothing But) Flowers.” The nervous, jabbing stabs of “Psycho Killer” (from Talking Heads: 77) lunge from the front speakers. The group’s soulful but edgy reading of “Take Me to the River” (from More Songs About Buildings and Food) bops and jerks across the surround field, Harrison’s keys squawking and singing — a perfect complement to Byrne’s vocals. The tribal Fear of Music track, “I Zimbra,” becomes a veritable orchestra of fascinating polyrhythms and interlocking parts.

With their mixing approach solidified after initial forays, translating the remaining six albums to 5.1 ended up being relatively uneventful. This isn’t to say there weren’t challenges and obstacles. For instance, the 1979 Fear of Music was recorded by a remote truck at the Heads’ Manhattan loft rehearsal space and “they used all these room mics that had tons of leakage in them,” Thorngren says. “It was a nightmare. On the album, a lot of stuff gets masked by the stereo, but when you start to spread it out — which was hard to do because of the leakage — a lot of abnormalities really stick out. And if there’s a vocal take on the overheads and it’s not the same vocal [that was used], that’s trouble, too.”

On the Heads’ final album, Naked (1988), the problem was multiple clicks and pops: The original was recorded on a Mitsubishi 32-track digital, and when it was transferred to Pro Tools (at Capitol Studios), the anomalies became apparent. “For that, we mainly used a Waves X crackle plug-in and that really worked; it was a savior for us,” Thorngren says. “It was a drag, but there was nothing we came across that we couldn’t fix.”

Other tools used on the second round of mixes included the Culture Vulture valve distortion processor (by Thermionic Culture of England), “and we also bought a stereo compressor from that company called The Phoenix,” Thorngren notes. “It has no transistor circuitry at all, so it’s like a really early compressor. It works beautifully on drums and it gives the bass a little more oomph.”

Listening to concentrated doses of the Talking Heads again, it’s hard not to be impressed by their skill, imagination and selfless dedication to the group gestalt. How did the music strike Harrison after all these years? “There were a few embarrassing moments, but most of the time, it was pretty great,” he remembers. “What really comes through is the sense of inventiveness and excitement. Everyone was aware we were charting some new territory, but we weren’t really sure where it was going.”

That is why the music still sounds fresh today — and better than ever in 5.1.