What is prog?

What is prog?

“Only gluttons for punishment dare try their hands at the definition of ‘progressive rock,’ as it is almost too extensive, too elusive, too amorphous and contradictory to put down on paper.”

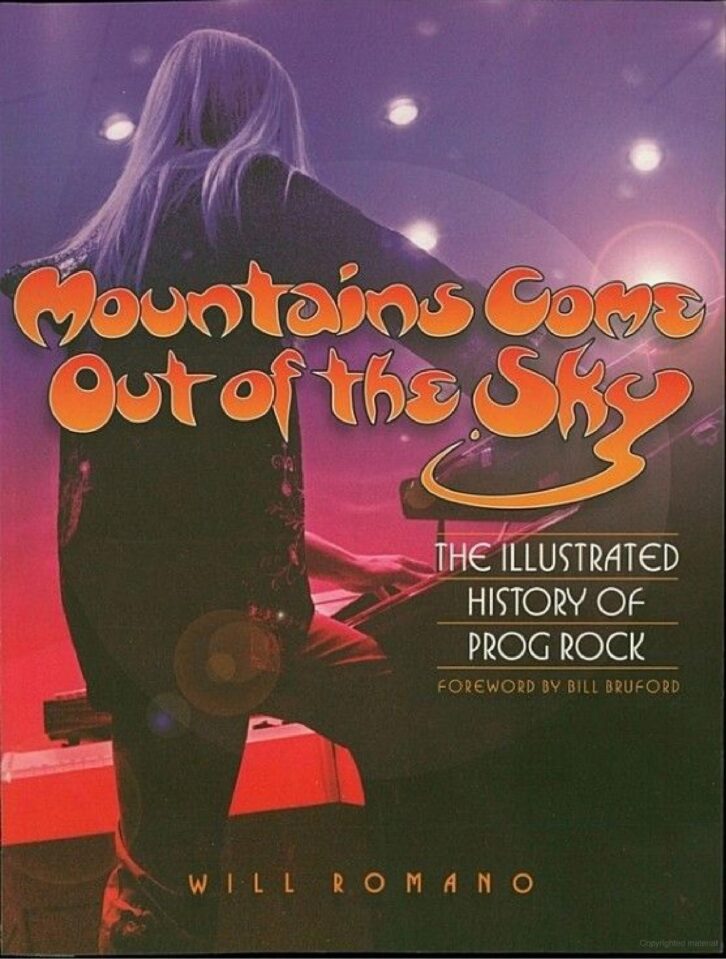

Thus begins Mountains Come Out of the Sky: The Illustrated History of Prog Rock, by Will Romano (Backbeat Books, $24.99).

The problem, observes Romano, is that every band might be called progressive: “Is a band progressive merely for evolving? Every band evolves.” Regardless, Romano, a writer who has contributed to EQ, Goldmine, the New York Post, Guitar Player and Modern Drummer, makes a valiant effort to define the boundaries of his thorough exploration of the genre. Arguably an extension of psychedelia, prog rock began to emerge in the late 1960s—starting with the Beatles, according to some of the performers interviewed for this book—and enjoyed halcyon days through the ‘70s before the newly emergent punk rock brought it to something of a screeching halt.

In truth, of course, prog rock never really went away. And while some bands were either breaking up (Yes, Genesis, ELP) or well past their prime as the 1980s rolled around (prog/jazz drummer extraordinaire Bill Bruford cites ELP’s 1978 album Love Beach, as “horrific” in the book’s foreword), bands such as King Crimson, Yes and Jethro Tull continued (and some continue to this day) to perform.

Romano devotes an entire chapter to each of the U.K.-based titans of the Golden Age of prog, including Pink Floyd, King Crimson, Genesis (“either the best or worst example of what it means to be a ‘progressive’ band,” according to Romano), and Yes. Slightly less enduring artists such as Gentle Giant, Colosseum, Greenslade, Camel and Mike Oldfield also get their due.

He explores the so-called Canterbury Scene, beginning with the Wilde Flowers, who begat Soft Machine and Caravan, who in turn spawned Matching Mole (with Robert Wyatt) and Gong. Prog folk—the Strawbs, Barclay James Harvest, Renaissance—gets a chapter, as do the Italian and German progressive scenes. And while the European classical music tradition informed the majority of prog rock’s main proponents, Romano also devotes space to a handful of North American bands, such as Kansas, Styx and, of course, Rush, that might be considered progressive.As any prog rock fan knows, many of the British bands of the era were initially defined by a certain keyboard sound. In one interview after another, musicians tell Romano of the importance of the tape-based Mellotron, with which many had a love-hate relationship. (King Crimson’s Robert Fripp once famously observed, “Tuning a Mellotron doesn’t.”) As some of the prog bands worked to redefine their sound, they were among the first musicians to adopt synthesizers such as the Moog Modular (famously a focus of ELP’s stage performance in the ‘70s) and the Minimoog (ELP’s Keith Emerson is also credited with being the first to commit a Minimoog solo to record).

Overall, the quality of the music began to suffer as prog artists responded to being labeled “dinosaurs” by the punks, aided by some ill-advised forays into pop, and the genre largely faded into the background as the ‘80s, ahem, progressed. But by the 1990s, it was starting to make a comeback, with newer bands such as Marillion, Dream Theater and Porcupine Tree keeping the flame alive.

In his final chapter, Romano notes, briefly, that an assortment of contemporary groups are carrying the prog rock banner forward, including The Flower Kings, Spock’s Beard, Coheed and Cambia, The Mars Volta, Opeth and others, while bands such as Radiohead and Muse also borrow heavily from the prog tradition. A selected bibliography and a discography of 297 of what the author considers essential prog rock albums round out the book.

Romano is an unapologetic fan of prog rock, and it shows. Crammed with color photos and interviews, this is an exhaustive and enjoyable study. Newer bands are given short shrift, to be sure, and some of the lesser-known artists are dismissed in a few paragraphs. Perhaps better sub-titled “The Illustrated History of the Golden Age of Prog Rock,” this is nevertheless a brave effort and reportedly the first book to even attempt to cover this oft-maligned music form.