Over the last few years, there’s been a growing interest in vinyl records—those big, black, round things that everybody over the age of 30 used to get their music on. Corresponding with this resurgence, there’s also been a rise in incredulous mainstream news articles covering the phenomenon, most of which can be summed up as “Look at these wacky, retro kids, buying LPs—whoda thunk it?”

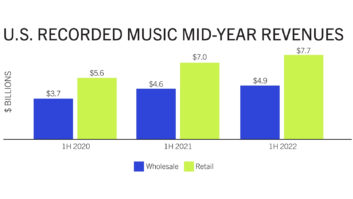

It’s not just a vague impression that hipsters are buying vinyl, however; there are hard numbers to back the trend. According to The Economist, 2.8 million LPs were sold in the U.S. last year, and vinyl sales are up 39 percent so far over 2010. It’s the same story in the UK, as LP sales there shot up 55 percent in the first half of 2011, according to the Entertainment Retailers Association.

Admittedly, this is all a drop in the bucket. The RIAA pegged the sales of vinyl LPs and EPs at 1.3 percent of all music sold in 2010, and it’s not as if overall music sales are going up anymore (Oh wait; they are. According to Nielsen, they actually went up 1 percent this year…thanks to downloads).

Nonetheless, records have hit the sociological flashpoint and become, well, Trendy. In fact, so trendy that you can’t call them “records” or “LPs” or “those big, black, round things that everybody over the age of 30 used to get their music on.” That’s “Vinyl” to you, thank you very much.

This moment has been a long time coming; John DeSimone, owner of Long Island Vinyl Exchange, told me this past spring how he’d been waiting years for a “Vinyl Revival,” he’d always known it was going to happen, and how he couldn’t wait to unpack the 100,000 albums he’d stored in a truck for years. As a retailer, he wasn’t excited to see an uptick; he was betting the store on it, getting ready to move to a larger location later this year that has already been decorated as the cover of Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti during remodeling.

But what will it take for this moment to become a movement? What will keep those hipsters buying vinyl three, five or 10 years from now? The key will be for retailers and the music industry to focus on the benefits of vinyl—and to make those benefits work for the consumer, creating an end-user experience that is better and more enjoyable.

• The Sound: Audiophiles have long maintained that vinyl sounds better than CDs (and MP3s, of course). Many insist it’s a better long-term storage medium for our musical heritage, too. At the least, there’s something to be said for listening to Boston’s debut album (AKA Boston’s Greatest Hits) on the medium it was created for.

• The Coolness Factor: The aforementioned Economist article makes an great point about the cultural cache that vinyl provides:

“People used to buy bootleg CDs and Japanese imports containing music that none of their friends could get hold of. Now that almost every track is available free on music-streaming services like Spotify or on a pirate website, music fans need something else to boast about. That limited-edition 12-inch in translucent blue vinyl will do nicely.”

• It’s Cheap: You can download “More Than A Feeling” at iTunes for 99¢—or buy a used copy of the whole Boston album for $3 at your now-not-so-local record store (or 50¢ at the garage sale down the street). At a time where no one has spare money for entertainment—and hipsters never have money—it’s hard to argue with a bargain like that.

But all of this mainly focuses on old (i.e.: used) records. The music industry thrives on presenting new acts, and getting people to invest in new music on new vinyl by new artists is a different story.

Given the still tiny demand, new vinyl is pressed in limited runs, especially in the indie scene where pressings of 500 or 1,000 copies are commonplace. As a result, finding records in the real world is difficult. Only a handful of national retailers carry any vinyl, and they have extremely limited offerings that lean heavily on reissues (Best Buy stocks that Boston LP for $24.99; can you say ‘Bargain?’ Me neither). That means the only way to buy new artists’ LPs is either at a well-stocked indie record shop (good luck if you don’t live in a major city), the occasional concert merch table, or online mail order.

City and Colour’s Little Hell

That last choice is the most common—and yet also the worst. First, there’s the twin problems of Wait and Weight. Consumers used to instant musical gratification suddenly have to wait 5-10 days for their package to arrive. Meanwhile, that package is gonna cost them, thanks to its weight. Today’s records, pressed on de rigueur 180 gram vinyl, are heavy, and often come in ornate packaging. If you buy them via mail order, you can spend upwards of $30 for one album between the price tag and shipping, as I did recently for City And Colour’s Little Hell (A great folk rock album, by the way).

Already, despite this being still early days for the Vinyl Revival, there’s a certain amount of gouging going on, too—seemingly every new LP that comes out automatically gets a gatefold sleeve, and many albums get split across four sides, all of which raises the price.

Such moves aren’t always necessary either; take that City And Colour album—clocking in at 47 minutes across four sides, it may improve the sound to provide so much real estate for grooves, but it smacks of just finding new ways to charge more. It’s not an especially user-friendly decision either: Having such short sides (one runs less than 9 minutes) is a nuisance. The album comes with a download code for high-end MP3s, but if a poor end-user experience nearly forces you to base listening choices on convenience instead of sound, then there’s no point in spending $30 on vinyl when Amazon will sell you the same album as MP3s for $5.99—and a quick, illicit-minded Google search will provide it for even less (as in “FREE”).

The Vinyl Revival has been a surprising but exciting turn of events, revealing that a new generation is willing to pay for music again, even if it’s for a fetish object like a vinyl LP. If this phenomenon is going to gain momentum and remain viable, however, the music industry is going to have to examine its pricing and distribution methods—the same two factors that aggravated its initial fall in the face of illegal downloading—and make sure it gets them right this time.

What do you think? Picked up any vinyl lately? Have an insight into the costs of record making? Share below in the Comments Section!