Ken Scott

For readers of a certain age, Ken Scott’s work as an engineer and producer has likely formed a significant part of the soundtrack to their youth. In a new autobiography, Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust, Scott shares his recollections of a career that kicked off at EMI’s legendary London studios (where he started in the tape library at age 17), spanned two continents and, along the way, helped define the sound of some of the icons of rock and jazz-rock.

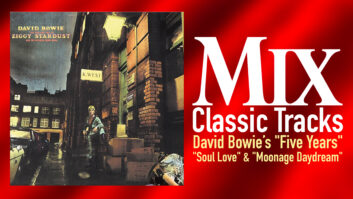

He might have never won a Grammy (the engineer and mixer were not added to the award credits in some categories until the turn of this millennium), but Scott has an enviable resume: Magical Mystery Tour and The White Album by the Beatles; solo projects by George Harrison, John Lennon and Ringo Starr; six albums by David Bowie, 1969 through 1973; Crime of the Century and Crisis? What Crisis? by Supertramp; multiple albums by the Mahavishnu Orchestra and, separately, drummer Billy Cobham; and albums by Elton John, Pink Floyd, America, the Rolling Stones, Stanley Clarke, Devo, The Tubes, the Dixie Dregs, Missing Persons (with whom he even tried his hand at management), and, more recently, Duran Duran.

Scott co-authored the book with Bobby Owsinski. “He recorded it, I mixed it,” said Scott. “That’s what someone came up with, and it’s a perfect analogy. I passed everything I had over to Bobby and he questioned me. He then wrote some chapters, passed them over to me and I turned them into my own voice.”

Even remembering a conversation yesterday, much less four or five decades ago, can be tricky for many people. Add to that the fact that an album session in the 1970s might take only three weeks and sometimes less, start to finish—blink and you would miss it—and an accurate memoir seems a daunting task. But Scott was determined to get the facts absolutely correct, contacting as many of the people with whom he crossed paths as he could find to ensure that their recollections matched his. He shares the memories of many of those colleagues and collaborators in the book.

The result is a tome rich in behind-the-scenes detail, from session notes and in-studio photos to insights into the creative processes of some of the artists with whom he worked, and plenty of high jinks besides. For those eager to learn Scott’s tricks of the trade, there are ample sidebars detailing such things as how the Beatles achieved their sounds and the typical technical setup when recording Bowie, from Hunky Dory—Scott’s first official production credit—onward.

The next album, Ziggy Stardust, launched Bowie’s career. “It was a great team,” recalls Scott. “We knew our strengths and each other’s strengths and weaknesses, and it worked amazingly well. Whether David would have achieved the success he had without that team, well, I don’t think he would have done.”

Notwithstanding the fact that he had access to some of his session setup notes, the fact that Scott could remember exactly what mic he used on what instrument on what project should not be too surprising. Indeed, it offers an insight into his enduring success as an engineer.

“I have a theory about this,” said Owsinski. “It dawned on me that Ken’s approach to EQ is somewhat different than everybody else.” Addressing Scott, he said, “You use the same microphones all the time. It seems like Ken is EQ’ing the mics rather than the instruments. So you can keep on putting different versions of an instrument in front of it because it will always capture it because he’s already EQ’ed the sound.”

“That goes along with what I’ve always said: It starts in the studio,” agreed Scott. “You’ve got to get a great drum sound—guitar sound, whatever—in the studio to get one in the control room.”

Owsinski recently invited Scott to engineer and mix a project that he was producing and got to see his process firsthand. “It was great to watch the classic way of doing it, and how easy it was for Ken. The typical thing for engineers today is to bring racks and racks of gear in; Ken brought nothing. He used hardly anything—a compressor on the bass, one reverb. And lots of dynamics; nothing was squashed. It sounded terrific without him breaking a sweat.”

It was—largely—another era, certainly, but Scott’s book still offers lessons for anybody serious about recording. And for everyone else, there’s also plenty to enjoy.

What exactly could be seen from an upstairs window at Abbey Road? And did that incident at the Missing Persons pool party really happen? You’ll have to read the book to find out.

Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust at Amazon