Friday, January 10, 2020

A few minutes ago, I learned of the passing of Rush drummer and lyricist Neil Peart. At first, I thought it was some kind of sick joke, but the tragic news is true. Peart succumbed to brain cancer at age 67. I’m heartbroken and have no doubt that the entire drumming community feels as I do—that we have lost a major inspiration and a brother.

Some of us will mourn by heading to practice spaces—spare rooms, cold, empty basements, or studios—to sit down and one more time mimic the man who set the high mark for generations of drummers. Others will mourn by listening to the songs that captured, thrilled and bewildered us. Neil’s death comes as a shock to the public because news of his illness had been kept out of the press—a testament to the respect for privacy given to Peart by his family and close friends.

Peart was an amazing drummer and a great lyricist. In the world of rock music, where lyrics are often centered around relationships and partying, Peart wrote about space shuttles lifting off, the hustle and bustle of city living, humanity versus technology, literary characters, and yes, trees talking to each other and acting like fools. Listening to his lyrics was like reading a sci-fi novel.

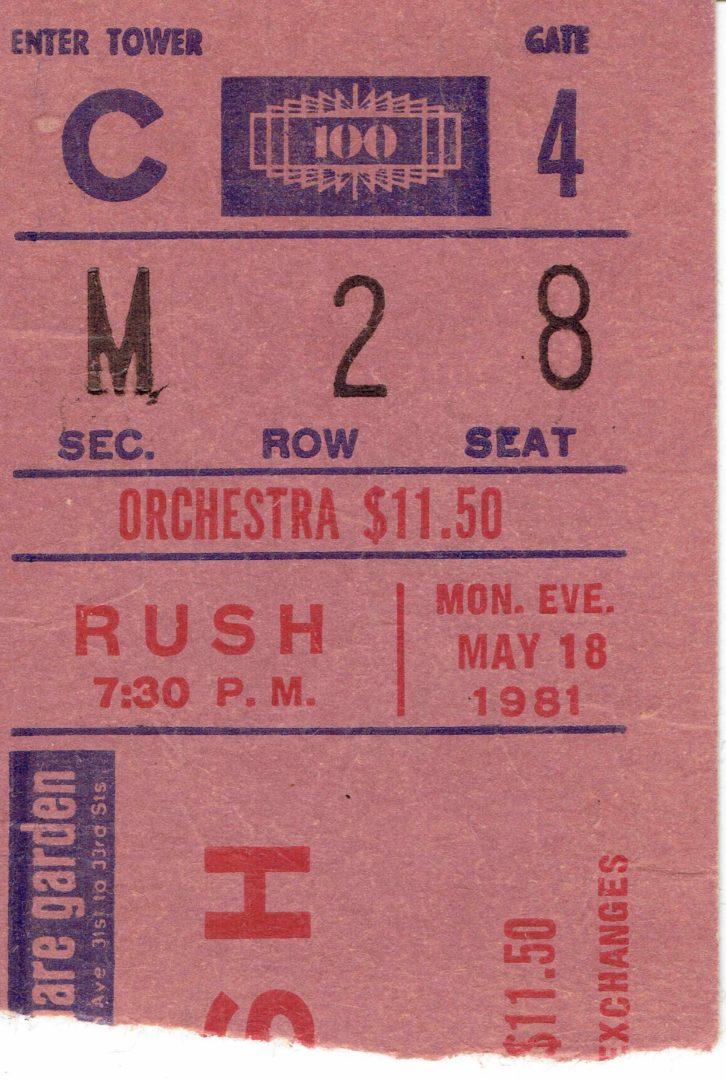

The first time I saw Peart perform was May 18, 1981. Several weeks prior, my high school music teacher and soon-to-be friend Vic Solotoff was talking about getting a group of students together to go to see Rush perform at Madison Square Garden. There was no doubt that I had to go see Peart play, and somehow Vic managed to get us tickets in the orchestra section. Moving Pictures had been released recently, “Tom Sawyer” was on the airwaves, and Rush’s star was rising (pardon the pun). You could feel it—that rare moment in an artist’s career when they transition from being a well-kept secret to an international force. It wasn’t just a concert, it was a phenomenon.

I remember that day with crystal clarity. It was a warm, sunny Monday. Earlier that day I was playing softball at school and crashed into the bleachers chasing down a fly ball. I banged up my arm pretty good and went to the hospital for an x-ray. No serious damage, but a perfect example of why you’re either an athlete or a musician —but not both.

My arm was in a sling and it hurt like hell. I was more worried about whether I’d be able to do a gig later that week with Vic and Double Barrel, the John Dewey High School Rock Band. I guess Vic must have called my parents to see if I was up for going to the show. I don’t remember that part, but I do remember him walking into our living room while I sat on the floor with my arm in a bucket of hot water. Vic walked in and with that beloved, sly grin said, “I can get Mike (so-and-so) to cover you for the gig.” I almost got up and kicked his ass. We ate dinner and headed for the show.

In those days you could still bring a camera to a concert without a photo pass or getting hassled. I had my brand-new Nikon FE 35mm film camera with me, though I wasn’t sure how I’d be able to handle it with one arm. When the lights went down, the entire floor section of the Garden stood up on their chairs and remained there for the entire show. Vic clutched the back of my t-shirt the way a lioness grabs a cub when she senses danger, while I awkwardly propped up the camera body with my injured arm and focused the lens with the other hand.

To say that MSG was rocking would be a complete understatement. Rush opened with “Overture,” “Temples of Syrinx” and then went into “Freewill.” The pain in my arm disappeared as I watched my new drumming hero put on a clinic. Somewhere I’m sure I still have those photos…

As my passion for drumming intensified, I tried to copy Peart, spending countless hours in the basement of my parents’ house learning to play the parts to songs with mysterious titles like “Cygnus X-1,” “La Villa Strangiato” and “Jacob’s Ladder.”

In those days this wasn’t an easy task because there was no technology for slowing down songs or isolating parts. It was, ‘Put the song on a cassette so you can wind and rewind a thousand times.’ I may have had one friend who owned a reel-to-reel tape deck, giving us the ability to record a song and play it back at half-speed in an effort to figure out what the heck these guys were playing. I’ll never forget the day I spent deciphering “YYZ.” When I finally got it, I was so psyched. I would later put it to use in a band with my dear friend Frank Manno, who took as much pride in learning the guitar parts as I did in learning the drum parts.

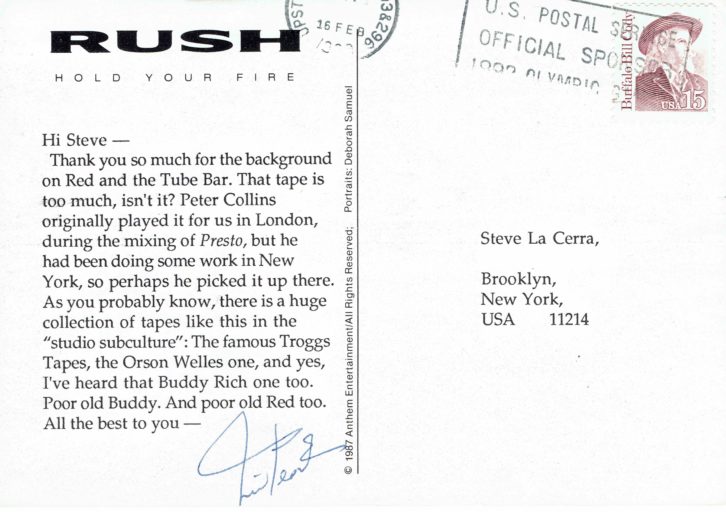

One morning when I was still living with my parents, I woke up and my sister was waving a post card at me. “You got a letter from the drummer in Rush!!!” What the heck was she talking about? I had forgotten that months before I wrote Peart a letter and he actually wrote back. How cool was that? He took the time to write back to me—in an era when that meant actually writing and sending a return letter in the post. Stardom with responsibility. I can’t seem to find that post card and to this day I still look for it. I know I have it somewhere. It was too precious for me to let it go. Neil and I had one or two other snail-mail exchanges, one of which is shown here.

Peart continued to influence and inspire my drumming, and even today I listen to his work in wonderment. How in God’s name did he come up with those parts? They were so unique, like nothing I (or anyone else) had ever heard.

The setbacks in Peart’s life are well-documented and will not be discussed here, but beyond music—in the real world—he’s an inspiration to anyone who’s had hardship in their life. He faced unbearable losses yet somehow managed to hold himself together. Eventually his spiritual compass brought him back to music.

And that’s where the beauty of music lies: it’s always there when you need it. It patiently stands by when you disappear for a while. It waits for you to cue up your favorite song on a phone, a car radio or even a vinyl record, or tune up your guitar. It brings you to a place you want to be. That’s a power that no one can take away. It’s a precious gift that Neil Peart and Rush gave to us, and we cherish it.

The Professor may be gone from this Earth, but he left us many lessons: Pride in one’s craft. Motivation to excel. Strength in the face of adversity. Grace Under Pressure.

Godspeed, Neil.