At Women’s Audio Mission, from left: Ulziisaikhan Lkhagvadorjv, engineer Jenny Thornburg, WAM founder Terri Winston, and Orgilsaikhan Chimeddorj.

Photo: Women’s Audio Mission

In April, San Francisco–based non-profit Women’s Audio Mission (WAM), dedicated to the advancement of women in music production, recorded a trio of master Mongolian musicians for a full-length album release, with funding from the Alliance for California Traditional Arts. Known as Nutgiin Ayalguu, which means “native melodies” or “melodies from home,” the trio comprises Orgilsaikhan Chimeddorj (aka Ogo), Ulziisaikhan Lkhagvadorjv (aka Ulzii) and Otgonbayar Chunsraikhachin (aka Otgo). WAM founder and chief engineer Terri Winston oversaw the tracking sessions with engineer Jenny Thornburg, while Thornburg mixed the album at WAM with Chimeddorj in May. Michael Romanowski completed mastering at his facility in early June; a release date for this album is pending.

While in the U.S., these three Mongolian musicians have educated audiences about their country’s culture, traditions and history, which have been passed down for generations through the music they play. Winston met Chimeddorj when he enrolled in her studio recording class at the City College of San Francisco, and she discovered the music as he demonstrated a Mongolian instrument called the Morin Khuur during a practice recording session. Winston became enamored with the music and recognized the importance of recording it as a means of helping to preserve Mongolian culture for future generations.

In the following Q&A, Winston details the evolution of the Nutgiin Ayalguu project, as well as the recording techniques that she and Thornburg devised, and shares its value as a reciprocal educational experience for the students of WAM and for the musicians.

What initiated the full album project? How did it come together?

It came together in stages. At City College of San Francisco, the Morin Khuur player, Ogo [Chimeddorj], shows up with this horse’s head fiddle, and I thought, “Wow, that’s really interesting.” When he played it, I was just totally blown away. He explained [that] this is the national instrument of Mongolia, and that song is a tradition that’s passed down orally: “That’s how we pass down our culture.” [Later] I was working on a film and I thought, this [instrument] might be cool in a part of the soundtrack, and it might be good if Ogo came over to the Women’s Audio Mission studio and just did something for fun. Originally it was just going to be Ogo, and then he said, “Well, I have a couple of friends, and one is this master throat singer.” And I [said], “Yeah! Bring them over!”

Orgilsaikhan Chimeddorj (Ogo) at Women’s Audio Mission recording the Morin Khuur, or “Horse Head Fiddle”

Photo: Women’s Audio Mission

They’re over here recording and my jaw was dropping! I was like, “Where did you guys come from? It’s crazy that nobody’s recorded you!” And they’re looking at me like, “What’s your problem?” That first video (“Mongolian Folk Musicians & Throat Singer”)

was just a one-day, one-off recording that we did with them really

fast. After that, I said, “Would you guys like to, at any point, do a

full record?” Ogo, of course, being the recording person, was the most

into it, so I kept in touch with Ogo. I said, “I think I could get some

grant money to do this.” They said, “It’s really great you’re

documenting this because [the Mongolian population in the U.S. is] a

really new immigrant population, so they’re losing their culture here.”

They’ve been here for maybe only the last 10 years, and I guess because

it’s an oral tradition; it’s been hard to get the really well trained

folk artists here. So it’s just kind of dying. When I talked to the

Mongolian Youth Center, they [said], “We really want our kids to retain

their culture, and music’s the only way we have to transfer that.”

So I was really excited. I didn’t know it was a new immigrant

population, I didn’t realize it was relatively small, and I also didn’t

realize how unique their music is. It’s totally different than anything I

had ever heard. It was just a really good collaboration, because it was

a win-win for everybody, all the way around. We had a lot of fun doing

it and we all learned a lot from it. They’re just amazing.

Ulziisaikhan Lkhagvadorjv (Ulzii) at Women’s Audio Mission

Photo: Women’s Audio Mission

We actually flew Ulzii [Lkhagvadorjv], the throat singer, out from

Chicago to do [the album]. Actually, Otgo [Chunsraikhachin] is moving

back to Mongolia, so it’s great that I got them, because he’s leaving in

September. And then we built up to documenting this. I think they

tracked 12 songs in three days. Everyone knew what they were doing.

The music that I heard in the video “Mongolian Folk Musicians & Throat Singer” was pretty striking.

Yeah.

Ulzii is one of the few throat singers trained in the origins of the

art form. They’re like rock stars in Mongolia [laughs], especially

Ulzii. He’s the one that everybody defers to: “Is this how it’s supposed

to sound?” When we mixed it, we had to make sure that we kept sending

it to Ulzii, who is an amazing throat singer. He will switch between

sounding like birds, and then it’s kind of a swirling vortex. He must be

pushing an enormous quantity of air.

How did you mic Ulzii? I understand you used an Audio-Technica AT-4050.

Well,

because there’s so much air, there’s no way you can get close to him. I

think we were able to use a pop filter when he sang by himself. They

have to be recorded together and they have to have really close

sightlines. So we had a few gobos up, but they’re used to performing in

people’s homes, so they’re used to being very close to one another.

Also, they did not want to have microphones close to them. The closest

we could get was probably a foot and a half. And that’s not that far off

from traditional mic technique. Because these instruments are pretty

unique, I was deferring to how they wanted it to sound. Because throat

singing is like an instrument, so I stopped thinking of it as a vocal

per se.

They were all very comfortable being in a recording studio, but they

were also very meticulous about how it sounded. They said, “We’re not

interested in sounding different than the tradition. We want it to be as

close to the tradition as possible.”

Otgonbayar Chunsraikhachin (Otgo) plays the yochin in a session at Women’s Audio Mission

photo: Women’s Audio Mission

I thought it was very practical that in miking these instruments, you

related their sounds back to sounds that you’re familiar with.

Yeah. The yochin [pronounced “yo-sheen“] is kind of like piano,

so we were using a stereo pair of small-diaphragm condenser mics. And

then it was more about, “Oh, the way he’s hitting those strings doesn’t

sound exactly like piano,” so we had to do a little adjustment. And the

Morin Khuur was like a cross between a violin and a cello, maybe, but

the strings are [made of] horsehair and they’re thicker than, say,

violin. So the bow noise is pretty prominent if you’re not careful about

where you’re miking that. And then when they were playing together, we

couldn’t mic things necessarily in the place that’s best for the

instrument all the time. So it wasn’t necessarily the best vocal-mic

placement or the best placement for the Morin Khuur, but we had to

switch things up.

Because the mic placement was less than ideal, were there other

things you had to do to compensate for that to capture the sound the way

it needed to be?

Well, yeah. It was like, okay, there’s no way you’re going to be able to

move those [mics] to where there’s no bleed. So then it was a matter

of, “That bleed sounds bad; let’s move it until the bleed sounds good,

so that when we’re mixing it, it’s usable.” It wasn’t as bad as I

thought it was going to be, because they’re such great players—it’s

almost like you could put up a mono mic in the middle of the room and

you’d be fine, because they’re all so used to compensating with each

other, in terms of volume. The good thing about the Morin Khuur is that

the body of it is really low to the ground, so we could get a gobo in

there and get a mic behind it, which was almost better. It was still a

little uncomfortable for Ogo to have that microphone underneath him,

facing the back of the Morin Khuur. But it did help in the way that we

had him seated. [The mic] wasn’t getting too much of the throat singing,

and the gobo was blocking out the yochin bleed.

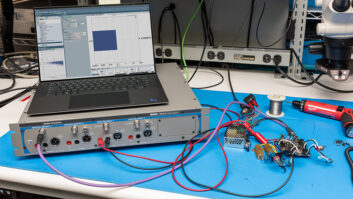

You and Thornburg recorded through Millennia and Great River preamps into Pro Tools HD2 using a total of seven microphones.

It

was tracked in Pro Tools HD2 with the Millennia A/Ds feeding the 192

[I/Os]. There was no processing going in; it was just straight to the

Millennia most of the time, and then with the Great River a couple of

times, on the Morin Khuur when [Ogo] would solo, because he plays

differently than he plays on the other songs, so it was a little

brittle. The Great River helped a lot, adding color in a good place. We

went for a super-clean signal path, because it’s risky when you start

grabbing for color when you’re not sure how they want those instruments

to sound. It’s not like an acoustic guitar that you’ve heard a million

times and you’re like, “I know it’s going to sound great with this.” So I

just really wanted it to go in clean. We made sure before we started

going through everything that [the musicians] sat down and listened to

everything and [we] said, “Does this sound right to you?” “Yeah, it

sounds exactly like it.” So then we just left it and went with it. It’s

not rocket science, as long as you’re paying attention and listening.

Most of it is listening to what they want.

From left: Otgonbayar Chunsraikhachin, Ulziisaikhan Lkhagvadorjv, Terri Winston and Orgilsaikhan Chimeddorj are pictured at WAM’s Webcast of a Nutgiin Ayalguu performance. The musicians are attired in traditional clothing for the performance.

Photo: Women’s Audio Mission

How did the mixing process go?

It worked out fairly

well, and Ogo helped mix it, so it was really nice to have him there all

the time. That was part of the deal. I thought it would be really great

for him; he could be a part of the recording. I like that he and Jenny

worked together on that. We mixed on a Sound Workshop 34C [analog

console]. We have some really nice outboard gear that was donated, so we

had some really nice outboard compression. We used it very sparingly.

We were using a [Summit Audio] TLA-100A [tube leveling amplifier]. They

definitely used the Manley Mini Massive [EQ] a little bit on the Morin

Khuur, because [of] the way we miked it. Both channels of the Mini

Massive were employed, I think, throughout the entire thing. We have a

couple of outboard API 550 EQs.

We mixed down through the [2-channel] Lavry Blue [AD/DA converter] into

[an Alesis] Masterlink [ML-9060 2-track hard disk recorder]. It was

pretty simple.

After recording and mixing, you hosted a Webcast of a Nutgiin

Ayalguu performance and held a discussion with the students of WAM about

these sessions.

It was great because the

musicians were here in their costumes. The audience got to hear what the

songs were about, what their costumes mean—all of their costumes have

some kind of meaning—and then we talked about how we actually recorded

it. So we got a lot of questions on, “How do you do that when they’re

all in the same room?” It’s just bleed. What people forget about bleed

is that when you’re sitting in the room, it sounds great. I sit in the

room and I go, okay, what am I hearing? All three instruments blended

together, so why are we so afraid of that? It sounds great.

You simply recorded musicians in a room.

I’m wondering if the

aversion to that is coming from the place where people aren’t in the

room with musicians anymore. It comes up from teaching, when I hear

these questions: “Oh, my God, what are you going to do?” Well, it’s not

the end of the world. [Laughs] It’s just bleed! Maybe we should give it a

less-medical name, something less painful—maybe a “mingling of sound”

or something. I don’t know.

I’m grateful for the Alliance for California Traditional Arts—they’re

paying for it. It’s great that it’s all getting documented. There’s a

lot of learning for everybody. We’re going to be doing another whole

series next year of traditional folk artists in the same vein because it

was just such a great, cool project. We’re going to do at least one or

two of these projects a year.

Matt Gallagher is a Mix assistant editor.

See photos of the mastering session for the Nutgiin Ayalguu project at Michael Romanowski Mastering.

Visit Women’s Audio Mission at www.womensaudiomission.org.