Tool is a dynamic band: intricate and intense, brutal and subtle. Each album is an aural adventure full of high-caliber musicianship, sick humor and sonic surprises. They create hard-edged, surreal portraits with driving polyrhythmic drums, deep churning basslines, dense guitar textures and passionate-bordering-on-deranged vocals interwoven with interesting sounds and effects. Obviously, they’re doing something right; the band has never been bigger.

The Tool lineup, from left: Maynard James Keenan, Adam Jones, Justin Chancellor and Danny Carey

Mix caught up with recording engineer/mixer Joe Barresi and mastering engineer Bob Ludwig to discuss the making of Tool’s latest album, 10,000 Days. Barresi has an extensive track record of working with hard-rock bands such as Queens of the Stone Age, Kyuss and The Melvins. Ludwig is the man with the golden ears who has mastered countless albums in every style. Both engineers relished the opportunity to work with Tool.

“I’d always been a fan,” Barresi says of the band. “And I had always wanted to work on their records just ’cause I thought it’d be an interesting combination — what I do and what they do. What really sticks out is their amazing musicianship. They are just ridiculous.”

After recording two albums with engineer David Bottrill (Aenima and Lateralus), Tool wanted to change things a bit. Melvins frontman Buzz Osborne, who is good friends with Tool guitarist Adam Jones, recommended Barresi for the gig. The band appreciated Barresi’s work on The Melvins’ records, noting his willingness to experiment with sound and recording techniques. Barresi describes the overall sound of 10,000 Days as “Undertow [the band’s 1993 debut album] on steroids.” To re-create the vibe of that album, the band returned to Grandmaster Recorders in Hollywood to track guitars, bass and vocals on the vintage 24-input Neve 8028 console. Drums were tracked on the API console at O’Henry Studios in Burbank, Calif.

“Part of the reason I chose Grandmaster was because they recorded Undertow [with engineer Sylvia Massy Shivy] there,” Barresi explains. “They were familiar with the studio; I’ve worked there. I just figured being there would bring back the sentiment of Undertow. They had tracked almost all of their records on Neve consoles, which I totally love. But Danny [Carey] wanted to do something different with his drums this time. He wanted to track on an API. He and I looked around town, and we settled on O’Henry. That’s where we spent a couple weeks tracking drums.”

Barresi tracked Carey’s extensive drum kit at the now-defunct O’Henry using the studio’s massive API console (more than 16 feet long!), which has 88 inputs fitted with enhanced API modules and traditional API-style 2520 amps. Barresi explains how he captured Carey’s kit: “I used a lot of close miking since he has such a large kit. I used three overheads: left, center and right. Then I filled in the other cymbals with spot microphones. The toms were all miked top and bottom. Kick and snare, pretty normal stuff. I had a couple of different stages of room mics: fairly close, middle of the room and then very distant. It was the kind of room where you could use the distant mics fairly loud without getting too much delay. What a beautiful-sounding studio!”

The album is loaded with electronic and acoustic percussion, all played live by Carey. “When I first showed up to their rehearsal,” Barresi explains. “I thought there were eight guys inside playing. I was like, ‘Who’s playing percussion in there?’ And it turns out that it’s all Dan. He has Mandala electronic pads that his friend Vince De Franco designed for him. He plays the Mandala pads, and they trigger sounds that he has sampled himself. It sounds like he has eight limbs.”

Barresi captured Justin Chancellor’s bass tracks with a combination of cabinet miking and DI. Chancellor played through Gallien-Krueger heads and Mesa Boogie cabinets. One amp was set to a clean tone and the other had a dirty sound. They were separated trackwise, so they could be blended at any point later. Barresi used Neumann U47 FET microphones on both cabinets. Additionally, Chancellor’s bass went through a Demeter DI box directly to the console.

Barresi explains guitarist Adam Jones’ recording setup: “Adam mainly runs three amps: He has a Marshall that he loves, a Diezel and then he was using a Mesa Boogie at one point. I brought in a Bogner Uberschall head and a Rivera Knucklehead Reverb, and several other things. Then we just experimented with combinations of heads and cabinets until it worked for the song. Most of the 4×12s were Mesa Boogie cabinets, which are superior for their low end, except for the Marshall head, which went through a Marshall cabinet, and the Rivera went through a Rivera cabinet. I usually used stock miking. For me, that’s a Shure SM57 and a Sennheiser 421 on every cabinet. The third mic could be anything that I felt the sound needed more of.”

The signal chain for tracking guitar was a bit complex. “Adam would play into whatever pedals he needed,” Barresi says. “That signal then went into a Systematic Systems Splitter. Then it would go to between three and five heads. The signal from the heads went to their own individual cabinets. Each cabinet had two or three microphones on it. Then all the microphones came back to the console, and they were blended down as separated for each amp. The Diezel amp went to its own track. The Marshall amp went to its own track. The third track was a blend of the Bogner and the Rivera, or whatever I liked for the song. And that would be one take — three tracks of guitar.”

On the song “Jambi,” Jones plays a solo that’s reminiscent of Joe Walsh on “Rocky Mountain Way.” Barresi tells how they went to the source to make sure they got it right: “Adam would always reference The Eagles and Joe Walsh for the sound of the Talkbox,” he says. “Bob Heil, who invented the Talkbox, came down when we did the Talkbox stuff. Bob actually has a line of mics that he’s been working on, and we ended up using one of his mics on the guitars, as well. It’s called the PR-30, and it’s a great mic! Joe Walsh actually called to give us some insight on how to record the Talkbox.”

Singer Maynard James Keenan has the ability to go from soft whispers to lung-busting screams. Keenan’s favorite microphone is a Soundelux tube condenser that’s no longer manufactured. “His main vocal mic was that Soundelux,” Barresi says. “Then there was some extra double-miking, and we’d use some other things for that. If I was gonna distort Maynard’s vocal, I would have him sing into his main mic and a highly distorted SM57 at the same time — a tape-them-together kind of deal — and then run them in a parallel chain so I could separate them and track them to two tracks. Then I could add any kind of gain that I wanted by bringing up the 57.”

Barresi brought several of his favorite pieces of gear to the Tool sessions, including an Echoplex analog delay, a Hiwatt custom tape echo unit and many WEM Copycat echo units. He’s especially fond of his Helios channel strip, which he used to track Keenan’s distorted vocals. There were other interesting custom-made pieces of gear used on the sessions, such as the “pipe bomb microphone.”

“There’s a guy named Rob Timmons at B-Band,” Barresi explains. “He makes transducers. Maynard was using a megaphone for some filtered vocal sounds, so I asked Rob to build me a few interesting mics to capture this. He made this thing called the ‘pipe bomb mic.’ It was a guitar pickup mounted to a piece of copper tubing, and it looked like a pipe bomb. I was using that inside of Maynard’s megaphone.”

Barresi used minimal processing when recording. “I tried to get by with as little as possible,” he says. “There was no EQ on guitar. There was really no EQ on the bass either. I EQ’d a little bit on the vocal. But if there was an effect on the vocal, then it would be drastic EQ’ing. I used a slight bit of EQ on drums, but I mainly got the drum sound by changing mics out: Like if I needed a little top end, I’d find a brighter mic. If I needed more bottom, I’d try a bigger diaphragm mic.”

Barresi recorded all tracks onto the Studer A827 tape machines at both O’Henry and Grandmaster. He used 2-inch Ampex GP9 tape at 30 ips. When he was happy with the tracks, he would transfer them into Pro Tools. “I call it the ‘holding pen’ ’cause all the tracks are in there,” he says. “Everything went to tape and then it got dumped into Pro Tools to preserve it.”

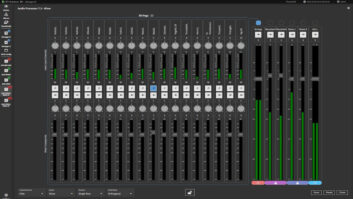

When it came time to mix, Barresi chose Bay 7 (featured in “L.A. Grapevine,” p. 124) and its SSL G+ console in Valley Village, Calif. Barresi mixed the songs on his own for a while, and then he would also work with each individual musician until everyone was happy with the mixes. They listened to mixes on a variety of monitors at Bay 7, including KRKs, NHTs, Yamaha NS-10s and Realistic speakers.

Once everyone was satisfied with the mixes, they flew to Portland, Maine, to master the project at Bob Ludwig’s Gateway Mastering facility. Ludwig used the Pyramix Virtual Studio DAW and a state-of-the-art Sound Performance Laboratory analog console. Ludwig, Barresi and the band listened through 800-pound Eggleston Works Ivy Speakers that are actually seated down to bedrock. Ludwig also used George Massenburg and Manley EQs on the project.

Even though Ludwig has mastered countless projects, he gets excited about Tool albums. “They’re a great combination of heaviness and yet huge dynamic range,” he says. “They’re one band that came in, and I think Danny said, ‘We don’t care if we’re the loudest thing on the radio. We just want you to maintain our dynamics.’ You have to really respect that in a band.”

Each of Tool’s albums has hidden tracks or sonic Easter eggs for the listener to discover. “Yeah, there’s things on this record,” Barresi reveals. “There are two in particular that are very interesting. One was a piece that Adam had worked on. We put it together while we were at mastering and in the hotel room the night before. We kind of tweaked it more the following day with effects, arranging and stuff.”

“There were a couple of little sound effects that were actually created right in the mastering room,” Ludwig adds. “It’s what they used to call musique concrète, which is music made from found objects or sounds that are manipulated. The last thing on the record is one of these musique concrète sound paintings that they have.”

The final format was a 96k sampling rate, 24-bit-resolution master, which they downsampled to 44.1k, 16-bit. “If any record deserves to be heard in surround sound, it’s this one,” Ludwig says. “There’s so much tone painting and so much color. It would just be a thrill to hear it in surround sound. And with 96k, 24-bit masters, we’re ready for any kind of high-resolution digital projects.”

10,000 Days is a rich listening experience. There are multiple layers of music and sound. Repeated listenings reveal more details. Typical Tool.

“I listen to a lot of Pink Floyd,” Barresi says, “and though Tool isn’t Pink Floyd, listening to an album a couple of times and discovering new things is part of the experience. You know, an echo or a part that would make you say, ‘What the hell was that?’”

“Their albums are like movies,” Ludwig concludes. “As a listener, I want to put their record on and play it from beginning to end to get the whole story because it evolves. You’ll hear things later in the record that refer back to earlier things. It takes you to many places. It’s really an awesome album.”