When asked, “What’s your favorite sound?” Sam Green, the Oscar-nominated documentary filmmaker who recently created the immersive ode to audio, 32 Sounds, replied, “I love the sound of water. I find it’s an endlessly fascinating sound. And it’s one of the inspirations for the movie.”

32 Sounds is an exploration of the phenomenon of sound. It describes what sound is physically and gives a brief history of recording and sound reproduction. It also demonstrates sound’s “power to bend time, cross borders and profoundly shape our perception of the world around us,” according to the film’s synopsis. 32 Sounds premiered at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival as an immersive, binaural experience presented to audiences over headphones, supported by live elements such as narration by the director and an original music performance by JD Samson.

Inspiration for the film struck Green as he was reading a book about composer Pauline Oliveros. It mentioned her lifelong friend, Annea Lockwood, who had been recording the sounds of rivers for more than 50 years. “Annea made several albums from those recordings,” he says. “One is called A Sound Map of the Danube, and there’s A Sound Map of the Hudson River and A Sound Map of the Housatonic River. I was completely intrigued.”

In 32 Sounds, Green meets up with Lockwood, who is on a recording expedition to Constitution Marsh, along the Hudson River north of New York City. She sets up her Sound Devices 702 digital recorder and drops a hydrophone in the water. In the film, she says, “I’m listening to a whole other world down there… The play of the currents underwater are delicious and make the most beautiful sounds. They have lovely phrasing. They’re musical.”

It’s this type of critical listening and outré thinking about sound that Green seeks to present in his film, which is concerned more with the act of truly listening than it is about the actual sounds in the film. While working on a previous documentary about Kronos Quartet, Green found that “it was a big challenge to get people to listen in an engaged way. Most of the time when you watch movies, you listen in a very passive way. With the Kronos Quartet, if you just half-listen, it’s pretty good, but if you really listen, it’s remarkable. I tried very hard with that film to get people to listen, and that got me thinking a lot about sound.”

TAKING TIME FOR SOUND

Green is typically a very deliberate filmmaker; he maps out an idea and has a clear sense of the story he wants to tell, but 32 Sounds was different in that it was a process of discovery. He filled his creative well from sources like the British Library Sound Archive, the Voyager Golden Record and even boxes of old cassette tapes from his closet.

“I didn’t know where this idea was going, and I think that can be powerful and can lead to powerful things,” he explains. “There’s that cliché about the sculptor with a big old slab of marble and how they allow the sculpture to emerge from it. It’s a corny idea, but it was true with this film more than any film I’ve made. I’m actually proud of the process and where it led. It’s not what I would’ve imagined in the beginning when I thought, ‘I’ll make a movie called 32 Sounds.’”

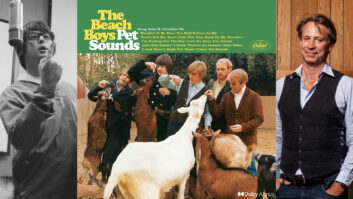

The director’s journey into sound led to a collaboration with two-time Oscar-winning sound designer Mark Mangini. “There are so many people who are smart about sound—from movie sound to sound art to composers to academics and sound studies,” Green says. “I talked to so many different people from many different disciplines, and Mark is someone who is really smart about sound. He’s so thoughtful and joyful about his work, and so I quickly glommed onto him as someone to talk to and ask questions.”

Mangini started as a sound consultant on 32 Sounds, helping Green figure out technical aspects, like utilizing binaural sound and having it play back properly for audiences. Green says, “Years ago, I saw a one-man Broadway play called The Encounter performed by Simon McBurney. He was on stage with a dummy-head microphone and everyone in the audience was wearing headphones. I remember being dazzled by the effect of him whispering in your left ear and whispering in your right ear. I was very taken with the effect of binaural sound—how it can work and the spatial quality of it. I wondered how to incorporate that into this movie, and Mark was super-helpful.”

Mangini spent more than a year talking with Green as he was researching, filming, writing and exploring the topic of sound and how it’s perceived.

“It was a two-year conversation, and I didn’t edit, record or even mix any sound that entire time,” Mangini recalls. “Sam wanted me to wax poetic on what I thought about sound, how I listen, and what I thought about his sonic goals—to think philosophically and to discuss sound as narrative and not make any sounds, although I did do that later.”

START WITH LISTENING

32 Sounds isn’t your typical documentary that’s mixed in stereo, 5.1 or Dolby Atmos formats and intended to play through cinema (or home) speakers. It’s truly meant for headphones.

“We built and mixed three versions for distribution,” Mangini explains. “A headphone-only mix (wide range) for streaming and online consumption; a headphone-only mix with bass augmentation for use in live theaters where we broadcast to headphones via a wireless, non-compressed, FM-based transmission system augmented by live elements; and we did a 7.1 theatrical mix.”

Because headphones can’t fully reproduce bass or sub-bass frequencies below 80 Hz, Mangini recommended adding a subwoofer to the audio playback system to supplement the headphone mix for the live events.

“I was concerned that the listener would not get the benefit of the full audio spectrum without it,” Mangini explains. “I encouraged Sam and the team to build the live performance with the ability to reproduce those frequencies so that the audience would have a very full and complete audio experience. This technical consultation was really important in crafting the sonic experience of 32 Sounds.”

Specific sequences—such as physicist Dr. Edgar Choueiri rattling a matchbox—lend themselves perfectly to binaural recording and playback via headphones, as the acoustics of the space in which the matchbox was recorded adds a sense of dimension and depth. As the rattling matches get further from the binaural mics in the dummy head, the sound of the space itself becomes more noticeable—just as you’d expect to hear if you were sitting in the room as Dr. Choueiri walked around shaking a box of matches. Listening to the film with eyes closed, it sounds as if someone is shaking a box of matches next to your left ear, then behind your head and then near the floor on your right side.

This effect would be difficult to reproduce with a 5.1 mix played back through wall-mounted theater speakers, as they would be too far away from the listener to generate the same sense of proximity delivered by a binaural recording heard through headphones. So for the 7.1 theatrical mix, certain sounds (like the matchbox) were re-recorded.

Green reveals: “Mark had this idea to record the matchbox in mono so that we could move it around the theater in the mix. Also, we should record it with a sense of proximity that matches the footage. Mark suggested going back to Foley artist Joanna Fang, who is featured in the film, and asking her to re-record these sounds in Foley to make them translate in the 7.1 mix.”

Mangini panned the mono elements around the 7.1 surround field to match the movement on-screen, and he used the Stratus 3D multichannel reverb from Exponential Audio to generate natural-sounding reflections to emulate the experience of the binaural recordings in a way that would translate in a 7.1 theatrical environment.

In another scene, Dr. Choueiri used the binaural dummy head to record his young son laughing and running around the backyard. Making this sequence work in the 7.1 mix was much trickier because Dr. Choueiri’s son was four years older than when the recording was first captured, so ADR wasn’t an option. To make it work, Mangini used one side of the binaural recording as a mono element that he could pan appropriately. Then he used the opposite side of the binaural recording to generate an immersive set of reflections by dropping its volume -10 dB and processing it with multichannel outdoor reverb and delay through The Cargo Cult’s Slapper plug-in. The addition of body movements and Foley footsteps in grass further aided the illusion.

“I knew the end goal was some version of reality,” Mangini notes. “It’s a sound moment; we’re showing off how spatial audio can be and how we’re not aware of it unless we’re told to listen to it, so we needed to take these measures to make it feel as believable as possible. I knew it would never be as compelling as the binaural recording, but it’s unique and fun in its own way.”

A TRUE SOUND EXPERIENCE

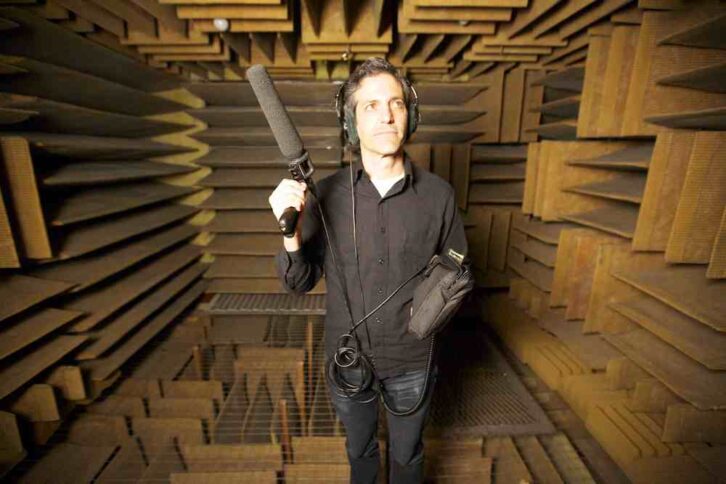

This was Mangini’s first time designing a 2-channel binaural track and mixing exclusively over headphones—no speakers to be found. He says: “For 46 years, I’ve been working in traditional cinema sound, listening to planar speaker reproductions, so I felt way out of my comfort zone. I had to rethink the way that I listen. Sam and I spent a week and a half together in my studio at Formosa Group with our headphones on the entire time. It turned out to be really fun and educational. I got to exercise new muscles in that process.”

It was also challenging in that the theatrical mix Mangini made in California wasn’t playing back properly during Green’s mix review at a theater in New York City. After talking to the theater’s projectionist, Mangini discovered that the Dolby Fader, which controls the volume that the theater audience hears, was turned down to 5 instead of being set at the standard level of 7 (85 dB).

“That’s 6 dB below reference level,” Mangini says. “The projectionist was very forthcoming, saying this is the starting point for them in the way most films are played because this is what makes audiences most comfortable. And so we had that philosophical discussion: ‘Who are we mixing films for? Is it the cinema? Is it the public?’

“Cinemas have been turning down the volume of movies because they’re too loud,” he continues, “so we make the mixes louder, making the cinemas turn the mixes down even further, and so we make them even louder. We don’t know what a standard volume should be for a theatrical release because theaters are turning the volume down.”

In the end, Green and Mangini decided to go with the standard cinema levels of 85 dB SPL, C-weighted, played at Dolby Fader 7, “because that’s what he wants the audience to hear,” says Mangini. In an effort to have theater audiences hear the film as intended, Green plans to include detailed instructions on setting volume levels to theaters—an approach that more than a few high-profile Hollywood directors take.

32 Sounds is more than just a documentary film about sound—at times, it even becomes interactive. In one sequence, Green incorporates a five-minute dance interlude and the audience is invited to get up and dance around because sound isn’t just something you hear; it’s something you feel, especially when sub-bass frequencies are involved. As Green notes in his film, “Sound not only goes in your ears, but hits your whole body if it’s low enough.”

In another sequence, he shows Pauline Oliveros’ Tuning Meditation (1971), performed and recorded in New York City on January 20, 2017. In this “meditation,” a room full of people are instructed to “inhale deeply; exhale on the note of your choice; listen to the sounds around you, and match your next note to one of them; on your next breath, make a note no one else is making; repeat.”

Sound isn’t just a physical feeling; it stimulates an emotional response, as well. In 32 Sounds, Foley artist Fang talks about how sound can bridge the gap between the visual and the sense of feeling the sound, as well as hearing it. In the film, she says, “Art can elevate a truth beyond what is feasibly there, and if we pull it off right, hopefully the emotional experience of hearing it and being a part of it is enough to make you fully accept the poetry of what you’re hearing. We’re trying to take what we feel on the inside, and have [the audience] feel the same way we do.”

Green toured with several live shows of 32 Sounds throughout California in March and early April. The 7.1 theatrical version is scheduled to open nationwide on April 28 with a screening at New York City’s Film Forum (distribution by Abramorama).

For those who do venture out to see the film, Mangini hopes that they walk away with the realization “that sound—often considered a secondary sense—isn’t given enough thought. It might encourage people to listen a little more often and a little more critically. Sound informs so much of the decisions that we make consciously and subconsciously every day.”