Good times at Studio D (L-R, seated): Anita Porter and Earth, Wind & Fire’s Philip Bailey; (standing) co-owner Joel Jaffe, producer Preston Glass and co-owner Dan Godfrey

THE HEART OF ROCK ‘N’ ROLL’S STILL BEATING

What many consider the “golden age” of recording gradually dimmed in the decade of excess — 10 years marked by jelly shoes and new wave, Rubik’s Cubes and the Material Girl — as engineers and artists became increasingly fascinated by all things digi and MIDI.

Much like the ’70s, real musicians, real instruments and heavy analog tape machines filled Bay Area recording studios, but at the same time, consoles (and hairdos) got bigger, expensive black boxes replaced EMT plates and echo chambers, and clunky CRT monitors and synthesizers occupied serious control room space. But despite the gradual infiltration of ones and zeroes, studios still reeked of cigarette smoke (among other substances), shards of 2-inch tape still hung from the ceiling and clients still locked out rooms for weeks — sometimes months — at a time to do pre-production, track, overdub, mix and master their albums, usually in commercial studios.

“There was a spontaneity in the early ’80s,” says producer/engineer Howard Johnston, who co-owned Different Fur with VP/general manager Susan Skaggs for almost 20 years. “Everybody involved knew what pieces of gear, mics and audio formats they were going to record and mix down to. Because of that, the ’80s were more collaborative. People needed each other to do sessions. There was a simplicity to that time.”

When musician/studio owner Patrick Gleeson sold Different Fur to Johnston and Skaggs in 1985, many assumed its demise. But proving the nay-sayers wrong, the studio stayed busy as ever with national and local clients such as Too Short, Bobby Brown, Devo, Bobby McFerrin, numerous Windham Hill projects (attracted by the studio’s Yamaha C7 Grand piano), Van Morrison, Gene Clark and Huey Lewis and the News, who recorded their demo there. “Patrick’s wife got him the [record] deal,” Johnston recalls. “She drove to Marin and put a ‘loaded’ cassette player on the band’s [now] manager’s desk.”

This is but one example of camaraderie taking place among the fake stone — covered walls, heavy baffles and high ceilings of the ’80s recording studio. “High-quality home recording equipment was only a fantasy — think TEAC PortaStudios,” says producer/engineer Ken Kessie, whose ’80s credits include Herbie Hancock, En Vogue, Santana, The Tubes, Sister Sledge and Until December (on S.F. new wave label 415 Records). “Great engineers were revered because they were the only ones who could operate all the equipment. Things weren’t corrected on a flat screen; they were done over and over until right. But then again, we would have killed for some of today’s preamps and modern mics.”

The vintage preamps and other gear at Different Fur played a role in great-sounding records by Gene Clark, Phil Collins, Bill Summers, Pablo Cruise, Stevie Wonder (with B.B. King), Bay Area guitarist/songwriter Jonathan Richman, Con Funk Shun, Hawkins Family and The Whispers, among others. Skaggs recalls grabbing drinks at a neighboring Mission District bar, The Chatterbox, with clients such as Tom Lord-Alge and members of The Starship. “Over the bar hung a petrified cat,” she recalls — as in rigor mortis, not taxidermy. “It was everyone’s favorite cat and bar.”

Over in Berkeley, Fantasy Studios kept busy with En Vogue, Journey, Aerosmith, Creedence Clearwater Revival and others on the Fantasy Records roster, while The Plant kept its vibe-y rooms booked with Kenny G, Aretha Franklin and locals John Lee Hooker, John Fogerty, Journey, Jefferson Starship and Van Morrison. In fact, it was at The Plant where producers Denzil Foster and Tommy McElroy first heard Kessie’s work and later asked him to commute to Richmond, Calif., to mix Tony Toni Toné’s successful debut, Who?, at Starlight Studios.

“They had heard me mixing a Con Funk Shun track and were impressed by this geeky white guy,” says Kessie. “At first, they acted thuggish. I had to push them out of the way to get the mix done. But I passed the test, and they were actually two of the nicest guys you’d ever meet — the polar opposite of thugs — and I continued to work with them for years.”

One of the most significant Foster/McElroy projects Kessie layed his hands on was En Vogue’s breakthrough, Born to Sing; again, recorded at Starlight Studios. “My career peaked with this band,” Kessie recalls of the female trio. “The console was mushy, the room and mics mediocre, but the talent and songwriting won out.”

CALIFORNIA ÜBER ALLES

Downtown in the Tenderloin District, Dan Alexander, Tom Sharples and Michael Ward purchased Filmways/Heiders in 1980 and named it Hyde Street Studios. Engineer John Cuniberti, who previously engineered at Alexander’s Tewksbury Sound Recorders in Richmond in 1978, became their studio manager/chief engineer. At night, while the homeless slept, the drug dealers hustled and prostitutes roamed the streets outside this nondescript building near Turk and Hyde, Cuniberti co-produced and engineered several albums for Joe Satriani, including his 1988 success, Surfing With the Alien, as well as three Dead Kennedy albums: Plastic Surgery Disasters, Frankenchrist and Bedtime for Democracy. “The way those D.K. records were recorded and mixed created an ambience that was atypical of other punk bands of that time,” says Cuniberti, who now runs The Plant’s mastering studio. “They were enamored with reverbs and delays — anything to make them not sound like the Sex Pistols.” The albums came out on frontman Jello Biafra’s Alternative Tentacles label (launched in 1979 in San Francisco and now based in nearby Emeryville), one of the most significant underground labels to date. Around the same time, clients such as Blue Oyster Cult, Leon Redbone and Ronnie Montrose occupied Hyde Street’s remaining rooms.

The Heider/Hyde Street legacy aligns closely with The Automatt, which remained a recording hotspot until 1984. Mastering engineer Paul Stubblebine, who would later open a mastering facility at Hyde Street, got his start at CBS, which later became The Automatt, honing projects for Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Con Funk Shun and U.S. releases on Rough Trade and Factory Records, including Joy Division and New Order.

In 1986, Alexander leased Hyde Street’s Studio C to producer Sandy Pearlman, who ran it as Alpha & Omega until 1991. In 1988, Alexander left Hyde Street to launch Coast Recorders on Mission Street.

DON’T STOP BELIEVIN’

While the “old guard” remained solidly booked in the ’80s, newer facilities such as the Music Annex, Russian Hill Recording, Studio D and Skywalker Sound, among others, began cutting deep grooves on the San Francisco scene.

Jack Leahy and Bob Shotland opened Russian Hill Recording in 1980 as a two-room facility, handling everything from advertising spots and independent film work to books on tape and music dates.

Partners Joel Jaffe and Dan Godfrey opened Studio D in 1983 as a way to fill a need for a live-sounding tracking room. “The Plant had three rooms at the time — A, B and C — and they were all pretty dead-sounding,” recalls producer/engineer Jaffe, also a session guitarist who has performed and recorded with several Bay Area bands since the 1970s. “As a joke, we named our facility Studio D — and it survived.”

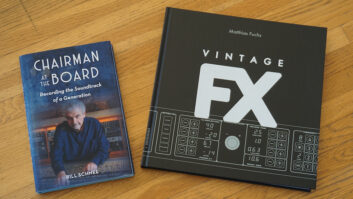

Opening the doors on their Sausalito space with a Trident A Range console, Studio D became known as one of the area’s premier tracking rooms, hosting sessions for Earth, Wind & Fire, Bruce Hornsby, locals Chris Isaak and Anita Porter, and a host of others to come. “It was a really cool time,” Jaffe recalls. “We were the new kids on the block, so everybody wanted to hear the new room. There was a great scene here. Major labels were coming up to work so business was good.”

Business also boomed down in Menlo Park, where Dave Porter, Russell Bond, Roger Wiersema and Harn Soper opened The Music Annex in 1976 after launching similarly named ventures in San Francisco and Palo Alto. “We played a fairly different role,” says Bond, longtime chief engineer and now owner of The Annex. “Our clients were always split between music and high-tech.” The five-room studio attracted such local artists as The Tubes, Ronnie Montrose and Journey, with Bay Area — based Windham Hill and its founder, Will Ackerman, as one of its biggest clients. Its Silicon Valley location also made The Annex a popular test site for high-tech companies such as Apple and Opcode. In the late ’80s, Porter opened the San Francisco — based post facility Annex Digital, which is now owned by Wiersema under the name Polarity Post.

Programmer Bob Smith, percussionist Greg Gonaway and Narada Michael Walden work out rhythm tracks at Tarpan Studios, formerly Tres Virgos, in 1987. Note ancient E-mu SP12.

Photo: George Petersen

The Bay Area’s recording scene flourished in the 1980s. In addition to more well-known facilities, others opened their doors in and around S.F. In 1985, Dave Nelson opened Poolside Studios, which later morphed into Outpost Recording, now located on Folsom Street. That same year, musician/producer Narada Michael Walden opened Tarpan Studios, where he produced mega-hits for Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey, among others. Producer/engineer Cookie Marenco’s home base, OTR Records, opened in Belmont in the late 1980s, as did her second home, The Site, in San Rafael. Prairie Sun hit the Wine Country (Cotati) in 1977 and continues to flourish. Other active San Francisco sites included T&B Audiolabs, Beggar’s Banquet, Phil Edwards Recording, Independent Sound and many more.

As the number of studios rose during the 1980s, so did competition and the demand for more inputs and more expensive outboard gear. “It was the hey-day of recording studios in many ways,” says Cuniberti. “Sessions started taking longer because there were more

options. Studios were selling more time, which was the greatest thing in the world for them, but they still had to purchase these huge consoles and tape recorders. So studios became bigger and more expensive, which eventually led to some of their demise.”