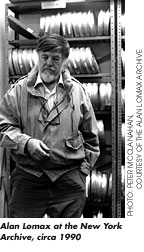

Not all humans are seduced by new technology. For some, maintaininga connection to loves past — such as turn-of-the-centurycylinders and discs — makes sonic time travel possible. Seventyyears ago, Alan Lomax went folk-song-hunting, dragging a disc recorder(quite literally) into the field. Rounder Records is slated to releasethe 90th master of the Alan Lomax Collection as part of an ongoingseries that spans six decades. That’s a lotta transfers!

Depending on the era, the media sources for Lomax’s material varyfrom aluminum disc in the early ’30s, acetate (on glass, metal orpaper-based discs until World War II) and then post war, from paper-and plastic-backed tape to vinyl (if the original source was no longeravailable). Generally, the discs are stored (and transferred) at theLibrary of Congress, while the tapes reside at the Lomax LibraryArchives in Manhattan. Tape transfers are either done in-house or atThe Magic Shop by Steve Rosenthal. Matt Barton, the archivist at theLomax Archives, took copious notes on condition, timing or any problemsthat were noticed during the transfer.

Discs were transferred in stereo to allow more options during thecleanup process; for example, one groove wall may be cleaner than theother. Generally speaking, summing two disc channels to mono greatlyreduces turntable rumble and can improve the signal-to-noise by 6 dB.But especially when considering the playback equipment used during thefirst-half of the 20th century, wear variations in the left and rightgroove wall can be so dramatic that it forces the engineer to chooseone over the other.

To investigate some restoration methodologies, I spoke with LarryAppelbaum, Brad McCoy and Mike Donaldson at the Library of Congress’recording lab. With all of the available resources, they each view theprocess more like a recording engineer choosing a microphone than likescientists — even though their work is at times more likearchaeology — especially when a challenging disc comes along. Inthat case, having stylus options can help to maximize the signal whileminimizing the interference, made all the more challenging by listening“flat,” with no playback equalization. Sometimes, theprocess yields two or three transfers of the same material, witheveryone hoping that one responds best to the least amount ofprocessing.

“Many of the early Lomax recordings were made on a blankaluminum disc,” Donaldson explains. “Whether it was thefault of the machine or the operator, the grooves were, in some cases,extremely shallow. The discs are not cut, as an acetate disc is, butembossed; at least that is what I was told many years ago. These discsare susceptible to corrosion from moisture in the air or salt fromfingertips, so many of them — from being handled over the yearsand from storage conditions before air-conditioning — have a bitof surface corrosion that sounds like a swish as the disc plays.Amazingly enough, an aluminum disc in mint shape can be hauntinglyquiet.”

With restoration projects, cleanliness is essential. “Unless adisc has deteriorated in such a way as to possibly risk further damageby cleaning, a Keith Monks record-cleaning machine is used to removesurface and groove dirt,” states McCoy. “A cleaning fluidis first applied and then vacuum-removed, followed by an application ofde-ionized water.

“There is no rule regarding stylus optimization, except tohave a selection to choose from and time to evaluate them,” McCoyadvises. However, even if the discs are clean, other problems canarise. “It can be hard to find a stylus that stays in a shallowgroove,” adds Donaldson. “Sometimes, a microgroove stylusworked [0.5/0.7/1.0 mil]; otherwise, a 2.2mil truncated stylus wasused. These are part of a whole series of styli made for us by Stanton.The earlier playback setup included a Stanton 500 cartridge, a TechnicsSL-1015 turntable and a Stanton 310 preamp set to flat equalizationpassing through a Neve console.”

Resolution is determined by the customer’s needs. “For thepast few years, we’ve been making 24-bit transfers for MattBarton,” says Appelbaum. “[Barton] either brings hisequipment down or we use our own Tascam DA-45HR DAT recorders. When itcomes to file creation and digital preservation, our current standardis [at least] 96 kHz/24-bit.” But the analog side is also underscrutiny. “We’re constantly upgrading our transferequipment,” says Appelbaum. “For example, we are currentlyusing the Simon Yorke turntable [with Vibraplane] and a KAB SouvenirMK12 phono preamp.”

FINDING THE SOURCE

After loading into a Sonic Solutions workstation, project masteringengineer Phil Klum’s first task is to edit the entire project byclosing gaps, cutting out unwanted chatter, pulling split pieces of aperformance together and removing mic hits. In some cases, it’snecessary to re-create something that has been damaged or cut in someway from the source, such as a guitar chord, a missed sung phrase oreven a spoken-word section that may be badly masked by damaged media.In the beginning, Klum recalls, any one of these processes took anentire afternoon, but these days, the team can complete the task withinthree hours.

With the editing complete, Klum then determines what type of sonicrestoration, if any, would be best for any given sound source. In thebeginning, Sonic Solution’s No Noise program was the primary solution.But after nearly 100 projects, Klum has taken many different paths,from varying types of EQ (analog and digital), using complex notchfiltering, manual de-clicking, and alternative de-noising and broadbandde-hissing techniques.

After any restorative processing — which, by the way, can takemany hours just to test pieces, retry different algorithm settings,etc. — it’s time to get to the other mastering chores, such aslevel, EQ, dynamics (if necessary) and the fine-tuning of edits, fades,etc. Klum comments that level adjustment is not only from track totrack, but also within tracks, as he often encounters a songthat sounds like the record level was radically raised or lowered,almost as though a knob was quickly moved during the recording. Othersections may have up/down level variations in increasing or decreasingamounts, as if the recordings were faded out and then back in, but atquicker speeds than you’d think a fade could be handled. He views suchchallenges as a sculptor smoothing a sculpture’s rough edges.

When the project has advanced to the first reference level, Klumcuts refs for the entire team to evaluate and makes any necessarychanges before cutting the master, which, in seven years, has gone fromPCM-1630 (in the beginning) to Exabyte to PMCD. Exabyte refers to theDDP format used as a master medium to ship to the manufacturing plants.It was considered to have very few errors per tape. PMCD (pre-masteredCD) is a format owned by Sonic and Sony. Exclusive to Sonic, a PMCD canonly be written on a Sonic DAW: PQ codes are burned into the lead-outof the blank disc. But that was then; many plants now accept CD-Rmasters as a matter of fact.

It may sound obvious but it’s true: There’s a fine line betweenremoving unwanted noise and going overboard. Lowering the noise flooror a set of noises beyond a certain point can reveal other noises thatmay be untouchable. So, again, the goal is a happy middle ground.

“From the beginning, our concern was to preserve the originalsources and their integrity by making it as easy as possible to hearwhat was originally recorded and documented by Alan Lomax, withoutgoing to extremes with regard to removing noise, sonic anomalies,etc.,” says Klum, summing up the team’s philosophy. “Theamounts of EQ and other processing have been employed only to‘bring out’ what we feel was there originally. Whatever theanomaly, on tape or disc, our goal has always been to go just farenough so that the listener can appreciate — without altering— all of the work Mr. Lomax compiled.”

For more information about (and to hear samples from) the Alan LomaxCollection, go to www.rounder.com/series/lomax_alan or www.alan-lomax.com.

For more fun, visit Eddie’s Website atwww.tangible-technology.com.