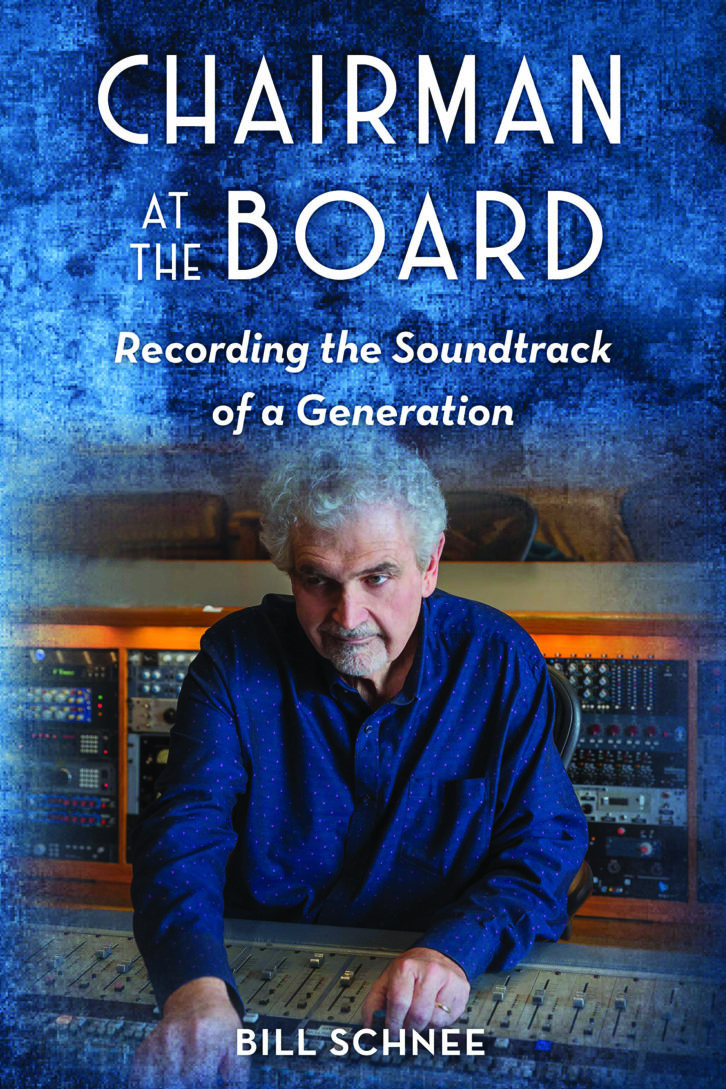

Chairman at the Board: Recording the Soundtrack of a Generation

By Bill Schnee, BackBeat Books

From the outset, engineer/producer Bill Schnee makes no bones about the fact that he considers the late-1960s to mid-1980s as the Golden Age of Recording, and he makes a good argument for it. The birth of the modern recording studio was in full swing, custom consoles and monitoring systems were growing out of thier custom, in-house roots to becoming actual products, and the techniques for tracking and mixing were just being discovered as engineers bounced around studios from Los Angeles to Nashville, New York to London, with a bit of the Bay Area thrown in.

Schnee, an engineer not typically mentioned in the same breath as the Al Schmitts and Glyn Johns’ of the industry, was in Los Angeles in the mid-1960s, the eye of the storm. After reading his memoir, Chairman at the Board: Recording the Soundtrack of a Generation, any reader would walk away thinking, “This guy belongs. Why don’t I know more about him?”

Chairman at the Board walks through a magnificent career in remarkable detail, with Schnee’s memory for names and places lending a credence and clarity to every anecdote. While the book advances largely in chronological time, from his debut as a musician in the L.A. Teens on through his work with Huey Lewis & the News, then Mark Knopfler, then early Whitney Houston, with a little soundtrack work thrown in. It’s a rich legacy of talent at the microphone. And yet, Schnee offers up equal respect and insights for the session musicians he worked with over the years, going so far as to list them, with personal comments, in an Appendix at the back.

The book is set up in chapters that focus on a particular artist and particular moment that marked a point in Schnee’s career. There is Three Dog Night early on, then Barbra Streisand, Harry Nilsson, Carly Simon, Ringo Starr (joined by the other three Beatles), Gladys Knight, Marvin Gaye… We don’t even get to his work on Steely Dan’s Aja until Chapter 11! Interspersed throughout each chapter are relevant asides and noted projects he was working at the time, as well.

There is certainly a lot of star power in the room, but it’s the early chapters regarding Schnee’s entry into recording, while his father was pushing for him to get a real career and he was going to college while working on his music, that resonate with anyone who has spent time in the recording industry.

There was Toby Foster, the guy who built a rudimentary console to replace the two-channel knobs that he was using at his first job, Mark Studio, and later pushed his name throughout Los Angeles. To this day Schnee cites Richie Polodor, who owned American Recording, the hottest independent facility in town at the time, as “the single most talented musician/engineer/producer I ever met.” (As Richie Allen, Polodor was a pioneering surf guitarist who co-wrote and played on Sandy Nelson’s “Teen Beat,” a pre-surf hit that influenced the surf sound–Dick Dale included it as part of his early live sets; in 1960 Allen/Polodor recorded as a solo artist for the Imperial label and scored a minor instrumental hit with the surf-styled “Stranger from Durango.”) Polodor took a chance on Schnee behind the board for Three Dog Night’s second record, and he provided Schnee with his first “a-ha moment,” setting a standard for what a record could “sound” like. He was his first mentor.

Schnee also gives a lot of credit to his relationship with producer Richard Perry, and to his friend Doug Sax, who taught him how to listen, as well as how monitors behaved. Sax was just getting his own studio, The Mastering Lab, going at the time. He would prove instrumental in getting Schnee into Producers Workshop and help him realize that quality recording mattered, that there was space and depth and emotion to be had.

The many in-studio stories are told in a matter-of-fact manner, to the point that at times you just go, “Are you kidding me? Then John Lennon walked into the room? Brian Wilson? Mick Jagger can be heard on ‘You’re So Vain’?” The dry manner almost doesn’t do a scene justice, but by the end, it’s clear that the straightforward approach lends even more magnitude to Schnee’s accomplishments.

The book includes a photo section, as it’s always a treat to look inside history. It also includes rich passages illuminating Schnee’s thoughts on technologies and techniques along the way, from that first 2-channel console (“You’ll thank me later in your career,” the studio owner told him, for working on “less than” equipment right now), to the entrance of the Wendel jr. electronic drum machine.

Throughout the book, Schnee casually mentions his working and personal relationships with the greatest engineering talent of the time. It’s clear that he belongs at the table.

One final note. Schnee is a thinker, and he has a set of personal philosophies. Many of those pop up throughout the book, while others are gathered in a closing Appendix. It’s these insights that help bring out a human touch, a reminder that these are people in the studio, making music, recording the soundtrack of a generation.