Thirty-five years after the launch of the compact disc and 30 years after the Macintosh II computer’s expansion capabilities birthed the DAW revolution, audio increasingly exists as zeroes and ones. This digital age offers many advantages, but there are also challenges, not least the security and preservation of these assets into the future.

Now that everything is data, data is, well, everything. As older analog assets are digitized and archived alongside newer, digital-born content, we find ourselves with a workflow that extends beyond delivery of the master. How do we ensure that we can return to that master in 10 or 20 years and still play it? What happens if we misplace it? If it’s stored with dozens, hundreds or thousands of other assets, how do we even find it?

Major record labels and motion picture companies rely on organizations such as Iron Mountain, the global information management service headquartered in Boston, MA, to keep their assets secure. The company maintains storage facilities worldwide, including underground, where it archives diverse assets, from government documents to music.

Greg Parkin, director of digital solutions for Iron Mountain Entertainment, reports that there are three studio facilities within his division at Iron Mountain that perform a variety of services for clients. “It’s a single chain of custody for the client; the assets never leave the facility. They never see the light of day and are protected in our very secure facilities.”

For clients with audio assets, those studio services include everything from running stems from the masters for use in the Guitar Hero or Rock Band video games to mold remediation, he says. “There were some assets stored in Miami, which was quite damp, that came to us in disrepair. One of our engineers has built a patented technology to handle very bad mold, with stunning results.”

The Recording Academy’s Producers & Engineers Wing has published a guide, “Recommendation for Delivery of Recorded Music Projects (Including Stems and Mix Naming Conventions),” that lays out the best practices and recommendations to ensure long-term archiving of and access to masters. It includes recommendations for reliable backup, delivery and archiving methodologies for current audio technologies that “should ensure that music will be completely and reliably recoverable and protected from damage, obsolescence and loss.” The document was initially released in 2002 and has been updated several times to remain current with recording and archiving practices. The AES has published a similar document based on those recommendations.

The document—indeed, common sense—dictates that data should exist on three separate media, with one geographically separated from the others. LTO remains the first choice for archival of digital assets. “The problem with hard drives is that they don’t spin up in 10 years,” says Parkin.

The linear tape platform, currently at LTO 5, was designed with a roadmap for future iterations. But like any other medium, it requires the data to be migrated as new technology supersedes the old.

Iron Mountain’s secure Digital Content Repository offers clients automated migration, says Parkin. “It’s basically a three-part backup within the system and then a fourth tape physically in our underground location in Boyers, PA.”

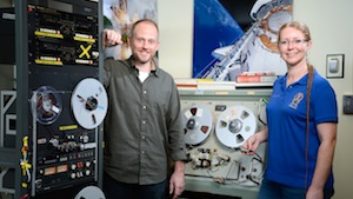

As for retrieving data from older machines, analog or digital, Iron Mountain Digital Studios’ director of technology Claus Trelby and his team have sourced, acquired and made operational almost every imaginable playback platform. “We have unicorn machines like a 3M 32-track digital. Clients come to us with unique source material problems all the time. Part of our business is being ready for them,” says Parkin.

Content owners should plan on printing alternative mixes such as stems, TV versions and vocals while outputting the masters. “Guitar Hero and Rock Band woke us up to retroactive archiving,” says Parkin. “It’s important to take that extra half day and print all of that so that you’ve got a single source of truth going forward. But at the same time, get it to LTO tape.”

Once archived, metadata becomes key. David Colantuoni, senior director of product management at Avid, comments, “There’s an endless quantity of machine-generated metadata at the acquisition point. Then there is metadata that is put downstream—user-generated as things are being logged, for instance, which might be as simple as ‘good take’ or ‘bad take.’”

Increasingly, metadata tagging is being automatically generated, either during acquisition—in cameras, DAWs and so on—or through software apps. “At Avid, we phonetically index the audio sources,” he says. “That’s essentially voice metadata that can be searched on. There are even more sophisticated systems that use facial recognition or scene recognition, where you are looking for signs, or a logo on a shirt.”

Google and other organizations have been working on recognition in moving images, but voice metadata is well established. “Think about a news organization and all the metadata that is being captured, then searched,” says Colantuoni. “You may need to be able to get something on-air within seconds, and have to search quickly for a particular clip.”

At the end of 2016, Avid launched its Nexis software-defined storage platform, driven by the company’s Media-Central platform. Unlike its previous offerings, Avid has sourced third-party hardware and created a software architecture that sits on top, he says.

“You can have hundreds of clients connected to it playing back hundreds of files of video and audio. You’ll see, in a news situation, 300 clients connected to Nexis, all working seamlessly and collaborating.”

The platform can connect to any number of storage and archive solutions. But, Colantuoni notes, “The Nexis file system is built so it can be extensible to the cloud in the future. If we wanted to kick-off an archive service that could be simply deployed, we could build APIs that enables companies to interact with it or we could do it ourselves.”

Metadata tagging enables search functionality, which in turn drives monetization of the assets. For instance, he says, “We’ve created logging applications that allow you to do tagging for specific functions. Major League Baseball records and logs every second of every game. They can search on anything.”

Monetization may be behind the decision to archive. Parkin reports that Iron Mountain recently completed a two-year project for MTV that involved digitizing 35 years of programming, from Beavis and Butt-head to Total Request Live. “That allowed them to monetize on their own, and have a direct channel: MTV Classic. That launched in August, 2016 and is doing very well. And we’re housing the original physical assets.”

The assets may not even be purely audio or video, but they may be related. For example, Iron Mountain mined the Warner Bros. sheet music archive at the University of Southern California on behalf of the L.A. Phil, which has been performing alongside showings of old movies. “We digitized the original handwritten scores,” says Parkin.

“It may not start in music, but that’s where it can end up. Future opportunities can arise out of something that you thought maybe was not necessary in the archiving process,” he says. “The affinity comes from music, but when you get into the cultural heritage of any artist, including unique assets such as costumes or journals, everything becomes valuable.”

Iron Mountain

Ironmountain.com

Avid

Avid.com