From left: Scott Avett, Bob Crawford, Seth Avett

In the decade since the Avett Brothers’ first full-length album, Country Was, the North Carolina country/bluegrass/folk/rock group has grown steadily in popularity, more on the strength of their live performances (and live recordings) than on the success of their studio albums. The acoustic trio—Scott and Seth Avett and standup bassist Bob Crawford—started to turn a corner with the outstanding 2007 disc, Emotionalism, their first to include cellist Joe Kwon (on a few songs).

But it was 2009’s I and Love and You, produced by Rick Rubin for his American Recordings label, that really changed their fortunes. All their previous albums had showcased the brothers’ solid songwriting, sweet and soulful harmonies, and instrumental versatility. On I and Love and You, all those attributes seemed to come into sharper focus. It’s a testimony to the Avetts’ talent and their broad, youthful appeal that I and Love and You made it into the Top 20 of the Billboard 200 album chart, and the Top 10 on that magazine’s Rock, Digital and Folk album charts (hitting Number One on the latter). Relentless touring and prestigious TV appearances sealed the deal.

I and Love and You was recorded over the course of about three weeks at the beautiful but now-defunct Malibu studio called The Document Room. According to engineer Ryan Hewitt, Rubin had an enormous impact on that album and the way the Avetts approached their songwriting.

From left: Bob Crawford, Ryan Hewitt, Scott Avett and Seth Avett on a break from their Laurel Canyon video shoot.

Photo by David Goggin

“The thing Rick brings to every record he does is that he is a song guy,” Hewitt says. “He doesn’t play guitar, he doesn’t sing, but he’s the mega music fan, and everything revolves around what’s best for the song. With the Avett Brothers, they’re young guys and they’d always gone into a studio and made a record in three or four days, and never really considered: ‘Should we change this? Is this the best verse to have here? Do we need this fifth chorus or this seventh verse?’

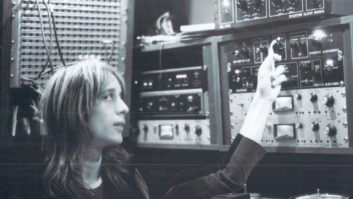

Ryan Hewitt in his Lock, Stock Studio, Venice, Calif.

Photo by David Goggin

“You go back to their early records, and while the songs are really fantastic, there’s very little song structure to some of them, and that’s part of what Rick really worked on,” continues Hewitt, who previously worked with Rubin on the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Stadium Arcadium. “If you listen to the live record we did [2010’s Live, Vol. 3] or how they play songs today, what they do now has clearly been informed by Rick’s method of breaking songs down and making sure that every part is necessary, that every part is complementary. They’ve changed a lot of arrangements of their old songs. Now, some of their fans loved the lack of song form, but from an accessibility standpoint, they’ve definitely improved. They’re able to bring their songs across more succinctly and more memorably, I think.”

The lessons they learned working with Rubin evidently stuck, too: When the Avetts started writing songs for their September release, The Carpenter—also produced by Rubin and engineered and mixed by Hewitt—the thought put into crafting and arrangement were evident from the start. As Rubin puts it, “The songwriting and preproduction on I and Love and You was arduous. On this album, the brothers owned all of the new ways of looking at song structure, and started way ahead.”

Adds Hewitt: “The difference between the last record and this one in the demos was this time they had the benefit of having worked with Rick, so the songs were a lot tighter. They came to Rick a few times out in Malibu [where he has a studio] and played him the songs and he’d say, ‘Wow that sounds great!’ They made a few changes here and there, but they really had tightened up their songs a lot before they got to Rick and they didn’t need as much rewriting and editing. They were pretty much ready to go.”

This time around, for various family-related reasons, the Avetts elected to stay in North Carolina to record the album, booking time at Echo Mountain in Asheville, a wonderful studio built inside what once was a Methodist church. The main recording room has a vaulted 20-foot ceiling with great acoustics, and the control room is based around a vintage Neve 8068 console. Scheduling issues prevented the album from being recorded in a single stretch of a few weeks this time; instead, sessions for The Carpenter were spread over nearly a year.

“I was flying back and forth to Asheville every five or six weeks to do a session of between five and 10 days at Echo Mountain,” Hewitt recalls. “In this case, the band decided they wanted to stay close to home. They didn’t want to go to Malibu [where Rubin has his facility, in the former Shangri-La Studios], and Rick gave them free rein because the demos were so good. So, I’d go to Asheville, record a bunch of stuff, come home, tighten things up in whatever regard I needed to, then do some rough mixes, take them to Rick and he and I would listen together and discuss what needed to happen.”

Scott Avett at Echo Mountain

Photo by Mike Beyer

This is not an unusual way for Rubin to work. As the producer notes, “We usually are in good enough shape preproduction-wise where we are clear what our goals are in tracking. I always try to keep as fresh a perspective all through the album-making process by never listening unless a decision needs to be made. On this album, although much of it was done remotely, I listened approximately the same amount, and was able to give clear feedback and then hear the band’s updates to my comments in a timely fashion.”

The currently touring version of the Avett Brothers is five musicians, incorporating the usual trio, plus cellist Kwon and drummer Jacob Edwards. That configuration did some live tracking as a group at Echo Mountain for The Carpenter—as on “I Never Knew You”— but Hewitt says, “It varied from song to song. Scott and Seth intentionally wanted to try different songs in different manners, so there were songs that were the whole band in there rockin’ out, and there was also a song that started with just Seth acoustic and then we built the band around that. The song ‘Life’ [which closes the album] was Scott and Seth playing and singing live in one take start to finish; the two of them facing each other with a couple of microphones.”

Asked if we hear much of the spacious church room on a track like that, Hewitt notes, “In general, Rick doesn’t go for roomy sounds, but I have mics there and sometimes I can cheat a bit of it into the mix. On that duet [“Life”] there’s a Royer stereo ribbon mic next to the two of them. I wanted it to be a little more like you’re in the room with them than the last record. The last one was very intimate and very direct sounding because of the nature of the room, really. But because we were in this big ol’ church, I wanted to take more advantage of that sound. I’m always recording room mics, because the song could take an unexpected turn in the production process, and they could be key ingredients.”

More often, though, Hewitt employed various plug-ins and outboard pieces for reverb and delays. On the moving ballad “Winter in My Heart,” for example, “I knew from the first time I heard that song it had to have a plate on it, so that’s a UAD [EMT 140] plate [plug-in] on that vocal. We used that quite a bit and the [UAD EMT] 250 digital reverb. I also got into their [Lexicon] 224 plug-in a little bit. I also have some outboard analog delays and some spring reverbs in the rack I like to use a lot. There were also songs where we printed some real plate at the studio that we really liked. Another thing we did when we were in Asheville is I sampled the room [into Altiverb] and used that later here and there—like if we had a percussion overdub from another studio, we were able to blend it better with the tracks from Echo Mountain.”

Indeed, that came in handy on some percussion touches Lenny Castro added later at Hewitt’s Venice Beach studio, Lock Stock. Other outside musicians who contributed to the album included Chili Peppers drummer Chad Smith on three songs, Heartbreakers keyboardist Benmont Tench (both captured at Rubin’s studio), drummer Steve Nistor (recorded at producer/engineer Tucker Martine’s Flora Studio in Portland) and a small horn section that was cut at Butch Walker’s L.A.-area facility.

That lo-fi horn part, on the funky New Orleans-ish song “Down With the Shine,” is one of several tunes that imaginatively blend crisp sonics with deliberately distorted elements. In the case of what Rubin calls “the Salvation Army horns,” Hewitt miked the players with RCA and Royer ribbon mics, “through Neve mic pre’s and then slammed them onto tape [via CLASP], distorting them in the process. Then I distorted them even more in the mix to make them even more dirty and nasty sounding.

The Avett Brothers album cover for The Carpenter.

“If everything is dirty, it doesn’t sound dirty anymore, it just sounds bad,” Hewitt adds. “And if everything is clean, it can sound a little boring. But when you have one or two elements in an otherwise pretty picture that are f—d up, it makes those things stand out more and it makes those elements more precious. It lets them play a cool role and hold things together as sort of textural glue.”

The album is full of those touches—unobtrusive background parts that add much to the overall richness of the album. There are subtle drone cello and organ parts that contrast nicely with crisply articulated acoustic guitars and banjo, fuzzed electric guitars that sit in reverberant fields far removed from the lead vocals, and treated piano that sounds completely different one track to the next.

“One of the main things I learned from Rick,” Hewitt says, “is to decide what the dominant factor of a given song is—what’s leading the song, what gets the spotlight. So, if it’s the acoustic guitar and vocal, then that’s what it is and everything more or less supports that. The vocal is always king. If there’s anything in the way of the vocal, it either goes away completely or gets ducked, so when you see the faders dancing on my console there’s some pretty big moves sometimes, all in the spirit of keeping the vocal in the front and not necessarily having to push it over other things. It’s more sculpting space out via panning and level and EQ and all the other things we have available to us to make that be the center of attention.

“When it comes time for cello or organ or some of these other things, everybody plays a role, and sometimes the role is to not really be heard and for the listener to not necessarily know what that thing is down there in the mud—but if you take it away, there’s this spirit or something missing from the mix. So it becomes this delicate balance of who comes in at what point in the song, and how loud they are and where they are—are they forward, are they reverb’d? I wind up recording a lot more than I need to and then taking it away even before it gets to Rick, because having been through this rodeo once before, I now have a better idea of where things should go.”

Recording the Avetts in Asheville was relatively straightforward, Hewitt says. To cut the all-important lead vocals, he used a Shure SM7 on Seth, an Electro-Voice RE20 on Scott, “and then if there were overdubs that didn’t have to match anything, I would go with a [Neumann] U47.” In each case, the mic chain also included a Neve 1073 pre and a vintage Black Face 1176.

Bob Crawford’s bass was miked with “a 47 wherever it sounded good that day. It changed depending on the song. I took a DI but I barely used it. I also ran him through an Ampeg B-15 with a 47 FET on it, because you can add more sustain to the instrument. When I mixed it, I would try to bus the mic and the amp and maybe even some DI, if I needed more attack from the fingers, through one compressor and squeeze them all together.” For banjo, he miked the instrument about a foot away with a Coles ribbon, but also ran the banjo through a Fender Twin and miked that for more sustain or aggression in certain places.

For Kwon’s cello: “A Royer 122 and a GML mic pre—because it’s super-clean and has tons of gain—and a Tonelux equalizer when I tracked it. I think I might have squeezed it a little bit on the way, probably with an LA-3A or LA-2A.”

The album was mixed at Hewitt’s Lock Stock studio on an Avid Pro Control surface and Tonelux summing bus, utilizing a slew of top analog outboard pieces and various plug-ins, with monitoring primarily through ProAc 100s. “Rick was totally involved in the mix,” the engineer comments. “I would work on a whole bunch of songs and maybe take six or eight of them up to Rick and we’d listen to them all in a row. You get a lot more perspective that way, rather than trying to concentrate on one song, finishing it and saying, ‘Okay, this is done.’ The other way, it’s like you’re listening to a lot of the record at the same time: ‘The drums sound way better on that one—what’s the difference?’ Then, we can address all those kind of issues in a number of ways.

“When Rick is happy, then we send it to the band, and these guys, they’re pretty easygoing. By the time it gets to them, it does sound really great, but still they have opinions and they have input into what’s going on, and I’ll get phone calls or emails to discuss ideas for changes.”

Is it hard to keep an overall perspective when a project takes so long and has so many breaks built into it? “It is a little difficult,” Hewitt acknowledges. “We spent a lot of time mixing and redoing little things in the middle of mixing and changing songs; editing. But every time we had some time off we’d plunge back in happily with fresh ears and fresh intent and remember why it is we do this thing.”

Clearly, a strong bond has been formed over the course of the two albums the Avetts have made with Rubin and Hewitt. “They are such fine people, it’s a pleasure to know them,” Rubin says, adding, “They’re wonderful songwriters, and forms and imagery continue to go deeper and get more personal as they do. I’m always excited to hear what they come up with next.”