Memphis has had an enormous influence not only on America’s music, but the very heart of our culture as well. It is the city that spawned Stax and Hi Records—crown jewels in the catalog of sound—as well as countless other highly regarded studios and recording artists. In the 1960s, the Memphis sound was comprised of heavyweights like Al Green, William Bell, Eddie Floyd, Booker T. Jones, The Staple Singers, Otis Redding and many others.

The Bo-Keys, formed in 1998 by multi-instrumentalist, producer and film composer Scott Bomar, continue to build on this rich musical heritage by writing and recording music that is authentic in the Memphis soul tradition, yet overflowing with fresh passion and vitality. Their latest album, Got to Get Back!, took seven years to complete and has won top accolades from music critics and fans both here and abroad since its release last year. Pro Sound News spoke to Bomar about the long journey that would ultimately became a modern-day soul masterpiece, and the measures he took to ensure an authentic sound.

On the Songs and the Players:

To get the sound that I would consider right for what we do, I have a Scully 1-inch, 8-track tape machine, and I feel like this is a big part of the sound of the record. I also have a Scully 1/4-inch, 2-track. The record was all done on tape, and I think that particular machine—which has Germanium transistors—has a really special sound. To me, though, the most important things are the songs and the players. The guys in the band are all musicians who have recorded a lot. They were studio musicians during the prime of soul music. Our drummer, Howard Grimes, did so many sessions in the ’60s and ’70s, and he really knows how to play in the studio—that makes a big difference. It is an art, especially for drummers. If the drums aren’t right, you’re in trouble.

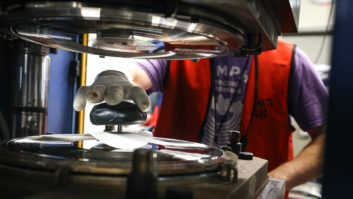

On Electrophonic Recording:

I put a studio together sort of by accident. In the ’90s, when so many big studios were getting rid of their analog gear and going digital, I started buying stuff, and also people would give me gear. My house at the time became a sort of orphanage for gear that other people didn’t want that was old or broken. I started fixing stuff up, and before I knew it, I had a studio. I have the Scully tape machines, and my console is an early ’70s MCI, a 416B—one of the first ones they made. That board was used a lot on a lot of soul records, and since the company was from Florida, they were in southern studios such as Muscle Shoals. I also have a plate reverb and a lot of vintage mics and amps. I think the tape machine and the plate reverb—combined with a chamber—were elements that gave our record the right sound.

On Tracking:

I will go in with Howard, and he and I get all the drum sounds together; then we’ll get levels on all the other instruments. We have two other engineers in Memphis that helped us: Kevin Houston, who was Jim Dickinson’s personal engineer for years; and Adam Hill, who works at Ardent Studio in Memphis. While I was out in the room, playing bass, they would be running the board.

We track everything live. Most of the time, it is the rhythm section and the vocalist, and sometimes the vocal we record with the band is the one we end up keeping. We may have to go in and punch in a couple of things, but we usually do the vocals and the rhythm tracks all together. On two of the tracks, we actually recorded the horns and the vocals together at the same time.

On Creating a Sonic Footprint:

The music that we love the most—and that we’re all the biggest fans of—was recorded at Stax, Hi Records, Muscle Shoals and American Studios. Those studios and places represent the music that we’re really into and that we do. I’ve studied all of those sounds as much as I possibly could. I dissected how they got them and I worked over at Royal Studios as an assistant engineer where the Al Green and Otis Clay records were done. That’s where Howard Grimes did most of the great catalog of music that he played on for Willie Mitchell.

On Mic Techniques:

For the Bo-Keys, I record things in a fairly standard way. I always do the drums in mono, and then I will do a stereo overhead. For the overheads, I’ll use a RCA 77-DX; on the toms and the snare, I’ll use Shure SM 57s. With Howard’s drums, I’ll mic the hi-hat with an AKG 451; he plays these huge Zildjian 15-inch hats, and it is a big part of his sound. On the kick drum, I usually use an Electro-Voice RE 20. Most of the vocals are cut on a late ’60s or early ’70s Neumann U87 microphone. I also have a Peluso 22 47 LE mic, which is like their version of a tube U47. On guitar amps, I will use the [Cascade] Fat Head II ribbon mic, which is really nice.

On ‘Got To Get Back!’:

The last song we cut on the album was [the title song] “Got to Get Back!” That was the song with Otis Clay. We had the record almost finished, but we felt like we needed one more song. When Otis came in and did that, I think that was a real magical moment. To me, the best part of any session is that first playback when you are in the room, you cut it, and everybody looks at each other and says, “That was the one.” Then you go in the control room, you play it and everyone is on the same page. When you cut the one, everybody knows it.