There was something audacious about it: a group from Scotland calling itself The Average White Band. If the funk don’t fly, then the honky jokes surely will. But these guys had clearly absorbed their share of James Brown, The Stax roster and the essence of American R&B. They could really play. Still, when AWB was formed in 1972, the music industry was starting to move away from the dance-based funk that was the group’s specialty, and there was little reason to believe that within a few years they would be riding the charts with a Number One debut album and a Number One single, “Pick Up the Pieces.”

Read more “Classic Tracks”

Buy the book

“The band was put together in London,” says rhythm guitarist Onnie McIntyre. “Glam rock was big — David Bowie, Gary Glitter and makeup were the rage. On the other side of the scale was progressive rock. A leftover from the days of Clapton and Hendrix, progressive rock consisted of endless guitar solos and an audience holding up matches as a tribute to their heroes. We formed the band as a reaction against the whole thing.”

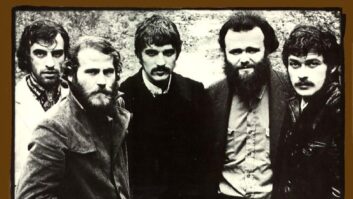

AWB featured Alan Gorrie on vocals, bass and guitar; Hamish Stuart, who traded off with Gorrie on bass and guitar and shared vocals with him; Roger Ball on keys, alto and baritone sax; Malcolm “Molly” Duncan on tenor and soprano sax and flute; Owen “Onnie” McIntyre on guitar and background vocals; and drummer Robbie McIntosh. The band would suffer a serious loss when McIntosh, the provider of crackling licks and a relentlessly solid foundation, died of an accidental drug overdose in 1974. Fortunately, AWB was able to attract Steve Ferrone to fill that seat for the next decade or so.

The original band started playing gigs in London without fanfare, but word quickly spread: AWB was a good-time bar band. “People started dancing,” McIntyre says. “Club owners loved us because they sold a lot of drinks when we played!” A cult following and a recording contract with the European division of MCA came in short order. However, their 1973 album, Show Your Hand, failed to generate significant sales. It was time for a move.

“We headed off to L.A.,” McIntyre recalls. “We fell right into that scene, where we found ourselves recording with Bobby Womack, Sly Stone and were introduced to lots of fabulous American musicians.” Owing MCA a second album, the group camped out at a friend’s house in the Hollywood Hills and began woodshedding the material that would form the basis of AWB, also known as “the white album.” The song “Pick Up the Pieces” was written during this period. McIntyre notes, “Hamish has a way of coming up with clever guitar parts, and the song developed out of the single-line lick that he played one day. Roger went off and wrote the horn line [played in unison by Ball on alto and Duncan on tenor], and the next day the rest of us fleshed it out.” Add McIntyre’s “chang-a-lang” rhythm guitar (panned hard left to complement Stuart’s chromatically inflected hook on the right), Robbie McIntosh’s hi-hat-heavy drum part and the lock-down bass line of Alan Gorrie, and only one ingredient is missing. “We wanted to have a vocal hook like James Brown used in ‘Pass the Peas,’” McIntyre says. Playing around with various alliterations, the group finally settled on “Pick Up the Pieces.”

It turns out writing the song was the easy part; tracking it was more challenging. “We actually recorded the album twice,” says McIntyre. “The first time around, we went into Clover Studios in Hollywood. Though the arrangements are different, [producer] Arif Mardin tightened them up and helped us focus on what was essential when we got to Atlantic; the material is mostly the same.”

AWB thought that they had a hit record when they turned their effort into MCA’s California office. But they ran into a problem that turned into a windfall when MCA rejected the disc and returned the rights to the group. Then, McIntyre says, “We heard that Jerry Wexler was in L.A. and were determined to get the album to him. He loved it and signed us to Atlantic.”

However, Atlantic felt the album needed a pair of new songs, and when “Nothing You Can Do” and “You Got It” were completed, the band was flown to Criteria Studios in Miami. “The sound quality was so much better than the work we’d done in Hollywood that Atlantic decided to fly us to New York to re-record seven tracks in their Manhattan studios,” McIntyre says. These sessions yielded the aforementioned Number One album and single, and a Grammy nomination for “Pick Up the Pieces” for Best R&B Single.

It’s hard to believe, but once there was a day when records were made without the benefit of 196 virtual tracks, digital pitch correction and surgical waveform editing. At Atlantic Records’ fabled midtown studios, it was all about capturing the moment. Classic records by the ton were tracked and mixed there — Aretha, Ray Charles, all the Atlantic masters had passed through the facility before AWB showed up. Many of them had been recorded by Gene Paul, the engineer assigned to the white album sessions.

Paul had an early education in music and recording at the feet of his father, Les Paul. “I grew up in the studio with my dad,” he says. “I even played drums with him on the road.” By the late 1960s, though, Gene tired of the drums and decided to make a career in the studio, on the other side of the glass. “I was so fortunate to get a job at Atlantic,” he says. “The philosophy there was very much in tune with dad’s. Dad had a great collection of vintage mics, and his recording sessions started with a very simple question: What’s the frequency response of the instrument you want to record? He’d put a [RCA] 77 on something when no one else would. Mics were his priority. He always used to tell me that it’s a mistake to overload a mic with frequencies that mean nothing.

“It’s funny. Everyone remembers dad for his multitrack innovations, but his first thought was, ‘How do you capture the environment?’ When I got to Atlantic, I was shocked at first. There were all these tools available, especially EQ! Lots of engineers there would plug in everything they could get their hands on. Then I hooked up with Tom Dowd and Arif Mardin. They went directly to the source, just as dad had, using as little extra gear as possible. The change in sound that Tom would get simply by making mic placement changes, moving an amplifier, was amazing.”

Paul already had a half-dozen Aretha Franklin albums under his belt, plus sessions with the Rolling Stones, Gladys Knight & The Pips and Wilson Pickett, when he was tapped to track AWB. “Pick Up the Pieces” was the first song he worked on with the group. “They were a phenomenal band,” he notes. “You knew immediately that they had it. ‘Pick Up the Pieces’ was so strong! Funny as it sounds, they put out another single first, and I couldn’t understand why!

“Miking-wise,” he continues, “I remember that we used Neumann 67s on the drums mostly, certainly on the hi-hat. We used an RE-55 on the snare and an SK-46 on the foot. That’s a bizarre ribbon mic, used by ham operators at RCA. But it’s phenomenal on the foot! It has that bottom end that you not only heard but felt. I remember that I used that mic to good effect on Roberta Flack’s ‘Killing Me Softly,’ as well. Back then, we were really into using Neumanns on the horns, too; they have a big, round sound. Remember, back at Atlantic, it was all about capturing a session, not processing and changing the sound.”

When Paul was hired by Atlantic, the studio had just recently moved from 8- to 16-track recording. “We had MCI consoles and recorders, running at 15 ips. Amazing, but they weren’t interested in quality in this area either! The industry was two or three steps ahead of Atlantic, technically. It was not a high-tech studio. In fact, my dad had a better studio out in New Jersey! We had a console with 16 faders, pan pots, switchers, and that’s it. If you wanted EQ, you had to go in the back and grab one! But look — that’s the room they cut Ray Charles in! My dad and I used to study those records.”

AWB’s album was mixed by Gene Paul and producer Arif Mardin. “It was a straightforward mix,” says Paul. “This was in the early days of Arif adding mixing to his production skill. I’d set up the rhythm section and he’d set up other things — horn parts, for example — and fold them into the mix. He’d guide things, from the tracking through the mixing. We had a great deal of respect for one another.”

Arif Mardin, too, has clear memories of the early AWB sessions. “The energy of the band was special,” he says. “All we had to do was get it on tape. Fortunately, we developed an instant friendship, and that showed in the music we recorded. As far as mixing the album, I used a distinct formula that was given to me by Tom Dowd. We’d put the bass nearly equal to the vocals in the mix, using an oscillator to check levels. Then we’d drop the kick drum 1 to 2 dB softer. Today, the kick leads. That’s the formula that Tom used in all of the classic Ray Charles and Aretha records. Then AWB had its own successful formula, which we simply tried to highlight — two guitar parts playing off each other, an active bass part and strong melodies.”

If Mardin downplays his own contribution to the band’s success, then McIntyre has another opinion. “It’s true that our records were very much a band effort, with Robbie at the helm. Arif saw the strength in that and made few changes. But I recently heard the original version of ‘Pick Up the Pieces,’ and Arif’s contribution to the later, better version was clear. He tightened up the arrangement, beefed up the horn section and highlighted the chant.”

AWB followed up their initial offering with a series of albums that yielded stronger material. Person To Person, Cut the Cake, their version of the Isley Brothers’ “Work to Do,” all show the band’s love for R&B and their own take on this quintessentially American art form. After almost 30 years, “Pick Up the Pieces” is still a living part of popular culture. Why? “I think ‘Pick Up the Pieces’ has something timeless about it,” comments Mardin.

Perhaps it’s the guileless love of R&B played by a group of young men from distant shores that shines through, combined with a touch of Bird-influenced “out” jazz (can you sing the horn line?) that glues “Pick Up the Pieces” to the public mind. Whatever it is, it’s sticking: The track served as the underscore to a Mitsubishi advertising campaign in 2000, was prominently used in a pair of major films recently — Bowfinger and Blue Streak — and is, not surprisingly, a staple of AWB’s still-popular road show.