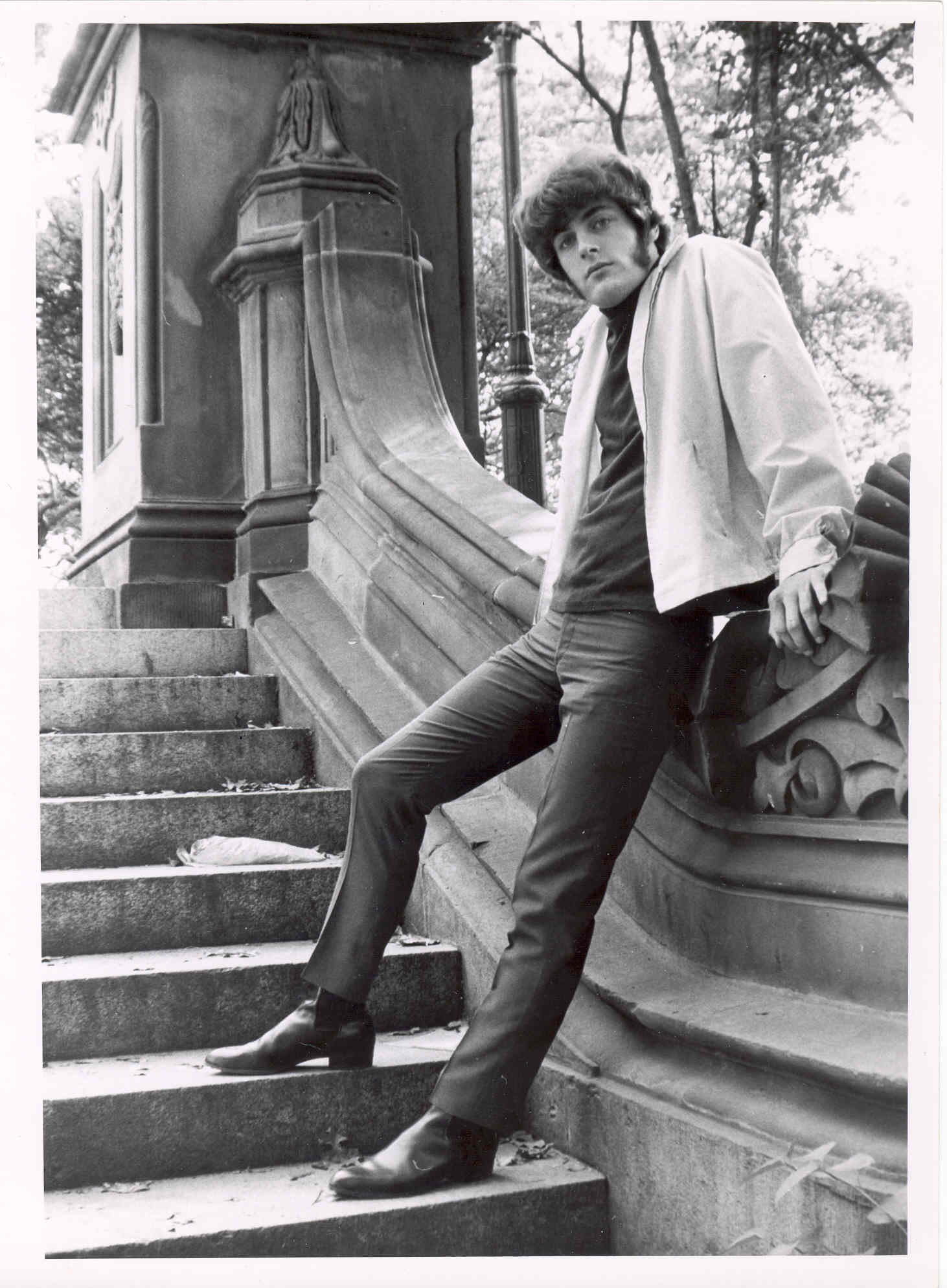

In early 1966, a dejected Tommy James arrived home in Niles, Mich., from what appeared to be the last road gig with his then-group The Koachmen, just in time to answer a phone call that would change his life.

Two years before, the group had recorded their first single, “Hanky Panky,” which was recorded at a radio studio by a local DJ, Jack Douglas, and issued by a small local label. “The record just came and went,” he says. “I graduated from high school in ’65, and I took my band on the road. We played Rush Street in Chicago and up through the Midwest, and we came home very out of work and depressed.”

But then James received that telephone call. “Hanky Panky” had sprouted new legs in Pittsburgh, thanks to numerous bootleg pressings from the original single. “They sold 80,000 pieces in 10 days, and it was the Number One record in Pittsburgh,” he recalls. James had a hit on his hands. “If I had missed that call, there wouldn’t have been a Tommy James.”

Unable to reassemble his original high school friends, The Shondells (a name he came up with in study hall in 1963 — “Anything with an ‘-ells’ on the end of it was cool,” he says), James says he went to Pittsburgh and “grabbed the first bar band I could find.” The band, The Raconteurs — Eddie Gray on guitar, Mike Vale on bass, Ron Rosman on keyboards and Peter Lucia on drums — headed to New York with James as The Shondells to find a real label.

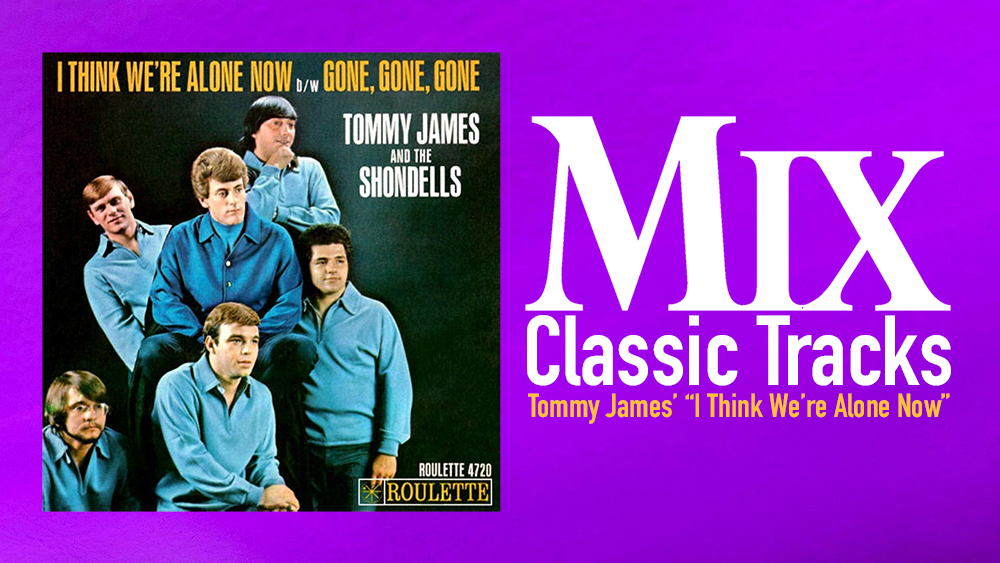

Initially, all the labels they visited — Columbia, Epic, Atlantic, Laurie and Kama Sutra — said “yes” to James and his group. But within a day or so, they each called to say they’d changed their minds — all except Roulette. It appears, says James, that Roulette “was pretty mobbed up. At the time, Roulette really was a singles label, but they didn’t have much going, from a creative standpoint. The last hit they’d had was in ’63 with The Essex’s ‘Easier Said Than Done.’” Label boss Morris Levy was ready for some new blood. “Jerry Wexler at Atlantic told us that Morris Levy had called all the record companies, and said, ‘Dis is my f***in’ record!’ So, apparently, we were going to be on Roulette.”

Levy quickly made an official national release of “Hanky Panky” on his label in June 1966, and it was a Number One hit within six weeks. That disc was followed by another, a cover of The Fireballs’ “Say I Am.” But James quickly realized that in absence of such a presence at Roulette, he would need to put together a production team to keep the hits coming. “I realized that my life, at that point, was going to be a never-ending search for the next single,” he says.

“I grabbed a bunch of people over at Kama Sutra,” whose offices at 1650 Broadway were located in the “Brill Building District,” the legendary songwriters’ haven. One of those people he “grabbed” was writer/producer Ritchie Cordell, who, with writing partner Sal Trimachi, provided James with his next single, “It’s Only Love.” “Almost immediately, after we put that record out, Ritchie changed songwriting partners to Bo Gentry, and, in November, they came to me with ‘I Think We’re Alone Now.’ They banged it out for me on a piano. It was a very slow ballad, but you could hear that it was a hit record. It had all the elements.”

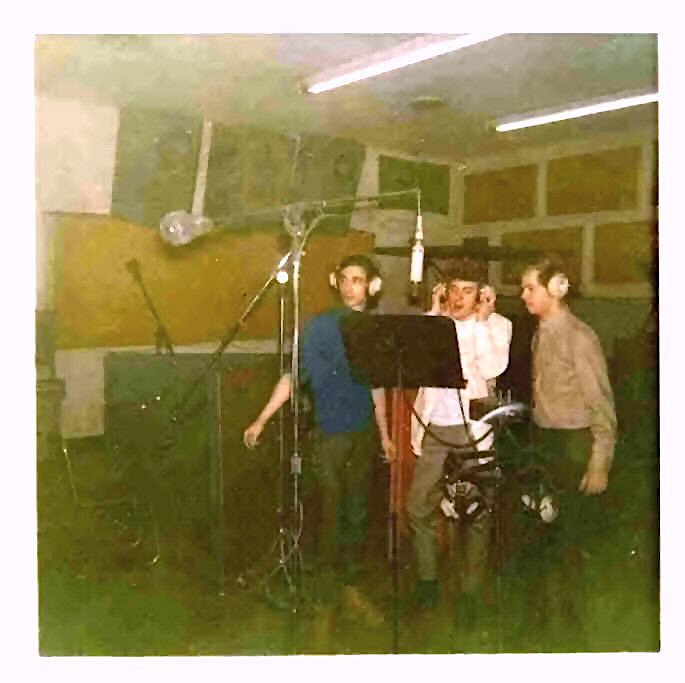

The trio went to the studio located in the basement of the building, Allegro, and recorded a demo, with James introducing the song’s distinctive thumping bass-plus-guitar eighth-note intro (a style known as “pegging”). “We sped it up. Bo sang the lead and I played guitar, and we took it back to Morris Levy and played it for him, and he flipped out. We all knew we had something really special there.”

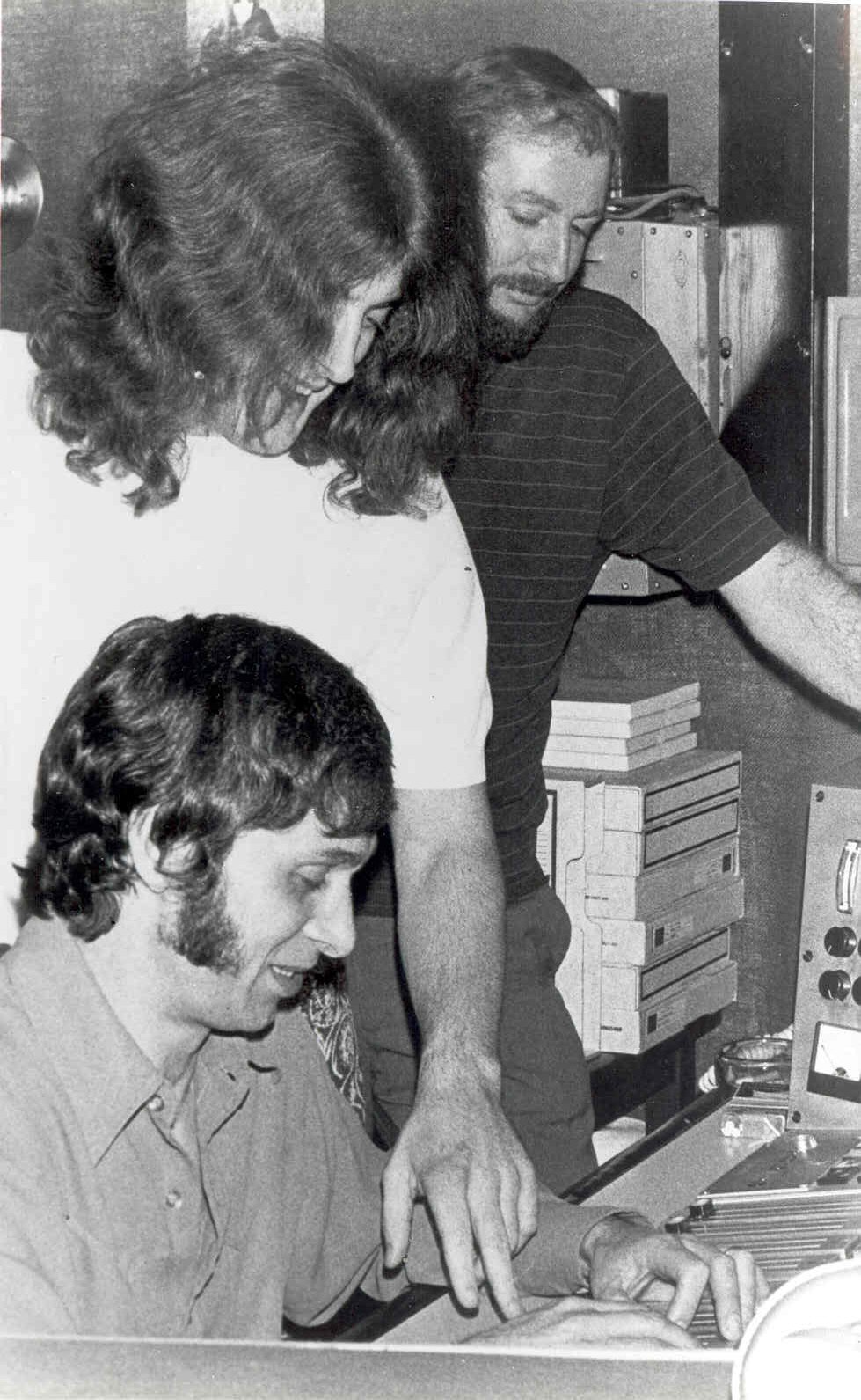

A month later, on Christmas Eve 1966, James, Cordell and Gentry returned to Allegro to record the song for release with engineer Bruce Staple. “It was originally Kama Sutra’s demo studio, which Bruce had built,” James recalls. “They kept upgrading and upgrading, and finally started taking outside clients.”

Staple had assembled a conglomeration of gear from Pultec amplifiers—a row of which, says James, made up the recording console. “It was very primitive. This was real bear skins and stone axes. There was a low-frequency hum on all of those old recordings—if you play them sped up, you can hear it. Plus, we were in the basement, and every time the subway would run through, we had to stop recording!” There was a single Scully 4-track recording machine, which played back through Altec 604 monitor speakers. “The Scullys were great,” James says. “At the time, you could punch-in on a Scully faster than any other machine.”

One of the first steps in the recording process for James was to hire an arranger. “I was asked by Morris Levy’s secretary if I wanted an arranger, and the first name that popped into my head was Jimmy Wisner.” James was a fan of Wisner’s (whom he subsequently dubbed “The Wiz”) after hearing his arrangement the previous year on Len Barry’s hit single, “1-2-3,” and spotting his name on the label, though Wisner’s history extended back to the days of Chubby Checker and Bobby Rydell.

Cordell and Gentry showed Wisner the song, which the arranger recorded on cassette to study. “The first thing I like to do is make sure the key and tempo are correct; it’s crucial,” Wisner says. “Generally, people don’t sing with the same energy in rehearsal as they do in the session because there’s no studio pressure. The excitement triggers a lot more energy in people. You generally need to compensate by making it a half-tone or a tone higher.”

The role of the arranger on pop/rock songs of the ’60s often overlapped some with that of the producer, though Wisner says that line was clear to him. “I didn’t write the song, I didn’t pick the song, I didn’t pick the artist,” he explains. “The producer runs the session.” But Wisner would work together with a producer like Cordell to craft the song into a surefire hit. “One important part of being an arranger is helping to format the song. People put their song together, but when it comes to putting a record together they may not have a good feel for, say, how long the intro should be or what kind of intro it should have. That’s where an arranger really comes into play. Where do you go after you go through the song the first time? Do you go right to an instrumental? Do you go to a different part? How long is that instrumental, if you have it?”

Another important contribution Wisner would make was the selection of musicians—even for an established band like James’. While pop bands like The Shondells, the Beach Boys, The Monkees and countless others might perform well live onstage, studio recording required something different. “The session guys in New York and L.A. at that time were very record-oriented,” Wisner says. “A lot of these bands, if they didn’t have experience going into the studio, as soon as that red light goes on, they’re just not that good. But we had studio guys who’d come in and knew and could be the band immediately, and they were relaxed with the recording process.”

Bands would go along with having substitute players, though they didn’t always like it. “I did three Spanky & Our Gang hits and The Cowsills’ ‘The Rain the Park and the Other Things,’ and they weren’t too happy that we didn’t use them. Though the family did sing background on the Cowsills track.”

In The Shondells’ case, only James and guitarist Eddie Gray played some muted guitars on “I Think We’re Alone Now,” and The Shondells sang some background vocals on the song’s fade. The main recording, however, was handled by legendary session guitarist Al Gorgoni (Four Seasons, Simon & Garfunkel and Neil Diamond, to name a few), veteran session bassist Joe Macko, drummer Bobby Gregg and pianist Paul Griffin (whose contribution was mixed out of the final recording).

The recording also featured another vet—Jeff Barry/Ellie Greenwich session pianist Artie Butler (“On Broadway,” “Leader of the Pack,” “Chapel of Love”). Butler performed on an Ondioline—a vacuum-powered keyboard forerunner to the synthesizer (the signature sound on Del Shannon’s “Runaway”), which played a high run through parts of the song. “I wanted something to do a long line,” Wisner explains. “It’s good practice when you have a rhythm going to have a long line over the top of it—either an organ or a sustain line. It goes against the rhythm, but it actually enhances the rhythm.”

The band recorded the rhythm track that Christmas Eve, placing drums (Gregg on a ragtag kit of various studio drums) and Macko’s Fender Precision (played through the studio’s old Ampeg bass amp—“with the tubs up top,” recalls James) and an electric guitar onto one track of the 4-track tape. The remaining chord instruments (including James’ trademark Fender Jazzmaster guitar played through a Gemini II amp) were recorded to a second track, with miscellaneous overdubs added prior to James’ lead vocal recording.

“I really discovered a lot about recording and producing from that record,” James says. “Up until that time, people would use a 4-track by recording everything live and then mixing to mono. This was the first time we began layering a record.”

In absence of a second machine, Staple had to ping-pong submixes onto an empty track. “You really had to plan way ahead of how you were going to submix prior to recording,” James notes. “Any one of your moves could ruin the record.” Prior instrumentation would, of course, be subject to generational losses during ping-ponging—all except whatever was last recorded onto a vacant track. “You’d have your final mix…and a tambourine. So the tambourine would be in your face, and the rest of your mix sounded like sweat socks!”

James triple-tracked his vocal, bouncing between the two open tracks before he, Cordell and Gentry recorded the song’s very-’60s background vocals. The song was then mixed for mono.

Interestingly, James notes, while the song opens solely with the “pegged” bass line, the song was actually recorded with the full band playing, though the mix doesn’t reflect that. “Most pop records were written in stairsteps,” James explains. “You’d start here, then the bridge would be here, building up to the full chorus. We went in the opposite direction—we stepped down to the chorus, which is almost bare,” except for a chirping cricket added by Staple from a sound effects record. (“The crickets were in the studio, too,” James says jokingly.)

“I learned a great lesson about recording for AM radio with that record,” James notes. “On AM radio, you’re going to fill up 100 percent of the speaker with something. If it’s two instruments, like a bass and a drum, each part gets 50 percent. So, geometrically, you make the record smaller when you add instruments. You make it bigger by having fewer things. On ‘I Think We’re Alone Now,’ the chorus was the quietest part of the record, but it was the biggest part of the record.”

While beginning a song bound for play on tiny portable AM radio speakers with a solo bass line would normally be a risky venture, the problem was neatly addressed by doubling the bass line with an electric guitar. “You had to make it very percussive so that it would cut through a small speaker,” the singer says. (James also noted that when the song was redigitized for XM radio, those scouring the vault mistakenly grabbed a previously unheard early mix that featured the full band in the intro, which now plays on the network.)

Mixing for AM also required “a lot of top end and midrange,” James adds. “You basically had to EQ things out of each other’s way, particularly because you’re mixing for mono and it’s all coming out of one point of your speaker.”

The song has never been mixed for stereo (though a “mock stereo” mix was created for the stereo LP release in 1967). Why? “Morris Levy didn’t want to take any chances with radio,” says James. “He just said [imitating Levy’s gruff voice], ‘No, that’s the mix!’ He didn’t want to change a thing. He wanted the hit.”

“I Think We’re Alone Now” was indeed a hit upon its quick release in January 1967, playing alongside such other classic tracks as The Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields Forever” and the Rolling Stones’ “Let’s Spend the Night Together.” “It was actually banned in Detroit for being too dirty!” James recalls. “This is at the same time that the Number One record was ‘Let’s Spend the Night Together.’” The song did have a curious effect, though, recalls Wisner. “We did a DJ convention 10 years ago, and a guy came up to Tommy, and told him, ‘You know, the first time I made out was with that record.’ It was a big moment for him!”