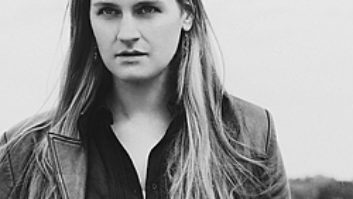

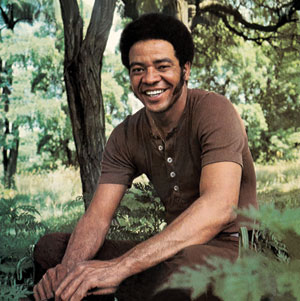

Bill Withers

Just a month ago, in our “Classic Tracks” column, Mix looked back at the making of “Ain’t No Sunshine” by legendary soul singer/songwriter Bill Withers. Well, it turns out we weren’t the only ones who think Withers’ music deserves revisiting. In November, Columbia/Legacy released Bill Withers: The Complete Sussex and Columbia Albums.

This beautiful box set includes all nine of Withers’ original releases, from Just as I Am (1971) to Watching You Watching Me (1985), remastered from the original analog tapes. Each disc is packaged with original album art, plus extensive liner notes, including an introductory essay by Withers.

This is the kind of reissue project that makes Sony Music senior mastering engineer Mark Wilder glad to be alive. “Can you imagine a better way to spend the day?” Wilder asks. “I get paid to listen to Bill Withers!”

Leo Sacks and Mark Wilder

Wilder remastered seven of the nine discs, while Tom Ruff handled Live at Carnegie Hall and Joe Palmaccio worked on the remaster of Still Bill. The project as a whole was guided by producer Leo Sacks, who has also collaborated with Wilder on monumental Legacy box sets on Aretha Franklin (Take a Look: Aretha Franklin Complete on Columbia, 11 CDs) and Earth, Wind & Fire (Earth, Wind & Fire: The Columbia Masters, 16 CDs). It’s clear producer and engineer have a great working relationship—not just because of their mutual enthusiasm for the music, but also because of a shared philosophical approach to reissue work.

“Great engineers like Mark and Joe and Tom aren’t just transferring tapes,” Sacks says. “They’re preserving music as a living language. They’re sensitive artists in their own right who recognize and appreciate where Bill’s music sits in the continuum of pop history. They also have great technical chops, which allows them to preserve Bill’s place in American music and introduce it to a new generation.

“So, they’re preservationists on one hand, and modern-day magicians on the other,” Sacks continues. “And I dare you to find their fingerprints, because we’re all incredibly mindful of how easy it can be to alter the original document with the turn of a dial. Occasionally we’ll use our professional judgment to roll some noise off the top or add a touch of mid, or give a little boost to the bottom, but we’re never consciously trying to change anything.”

Sacks and Wilder began the Withers project the way they do all of their Legacy work, by ordering the original masters from Sony’s archives and then assessing their playability, baking tapes that need it, finding the best playback machine for each tape. Wilder’s room at Battery Studios (New York City, batterystudios.com) is well-fitted for the job with vintage Studer and Ampex machines.

“Once we know we can play back the tape optimally, we start to listen to the original LPs for comparison,” says Wilder, a Grammy winner for his work on Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis and Billie Holiday catalogs. “At this point, we’re making ‘triage’-type decisions. We’re saying, ‘They did bass summing here because they’re fitting it onto the vinyl, but do we need to do bass summing for a digital release?’ My Maselec console has bass summing, and it has an elliptical filter, so we have the ability to listen and say, ‘It’s part of the vibe, so we’re going to do that.’ Or we will listen to high-frequency limiting [the same way], for example.

“We go through each of the elements that we hear on the vinyl, compared to the tape, and then we start making choices about EQ, compression, converters. The idea is to match the essence of the music on the LP and to give it that extra love as we take it to the digital world—to carry forward Bill’s, as well as the original engineer and producer’s, vision.”

Wilder’s racks contain many specialized and vintage models, including API 5500, Sontec MES-462C9 and EAR 825Q EQs. He monitors on Duntech Princess speakers. Like many mastering engineers, Wilder operates kind of like a chef, adding small amounts of many ingredients to obtain the richest result.

“This isn’t like mixing where you have individual elements that you can change,” Wilder says. “I’m making global changes. For example, a song such as ‘Use Me’ is very groove-oriented. You want to make sure that foundation is moving properly. You have to be careful, because if you make it overly bright, you draw attention away from that.

“So many of these songs I remember from childhood,” Wilder concludes. “I remember sitting in the back of the car—my father got a new Mercury Cougar in 1971—on the way to the grocery store, hearing ‘Lean on Me.’ The songs are ingrained at a cellular level. So when I hit Play on one of these masters…it’s indescribable, hearing that come through my console and my speakers. It takes you back, but at the same time you’re in utter awe of that moment. So, my approach is really that I want to hear this tune the same way I heard it as a child. I want that emotional connection, and I want to sustain that connection through the [mastering] process, to make sure that feeling doesn’t get lost through the decades.”

Check out Mark Wilder working on his Maselec mastering console.