Anne Dudley, the Oscar-winning composer of the score for The Full Monty, took a cue from the title of the standard English hymnal when she named her new classical music CD Ancient and Modern. But in Dudley’s case, the words “ancient” and “modern” are resonant in other, meaningful ways: They could be metaphors for the emergence of pop music figures such as Dudley, Danny Elfman and Randy Newman, who create often classically infused instrumental scores for the modern medium of film. And the title could describe the professional life of the London native, who has a grounding in the classics and a reputation as a pop music pioneer with Art of Noise.

Dudley’s brilliant career began at 12, when she won her first scholarship to the Royal College of Music. She eventually studied there full time, but the child piano prodigy would still sneak a transistor radio into the bathroom, against her parents’ wishes, and listen to the latest tunes from The Beatles and Motown. Dudley got her chance to shape pop music herself when, 18 years ago, she met producer Trevor Horn while playing on the cover-band scene. The meeting led to her keyboard and arrangement contributions on hit songs such as ABC’s “Look of Love” and Malcolm McLaren’s “Buffalo Gals.” She later started Art of Noise with Horn and fellow session players Paul Morley and Gary Langan (later replaced by Lol Creme), scoring Top Ten hits with “Close (to the Edit),” “Peter Gunn” and “Kiss,” and making an impact on techno, dance music and pop with her experiments in sampling and remixing.

In demand as an orchestral arranger and keyboardist, Dudley has collaborated with artists ranging from Paul McCartney, Annie Lennox and the Pet Shop Boys to Queen Latifah, the Spice Girls and Pulp. But possibly her biggest break came when she got an opportunity to compose for British TV programs such as Jeeves & Wooster and Kavanaugh QC, and then films, including American History X, The Crying Game, Buster and Pushing Tin.

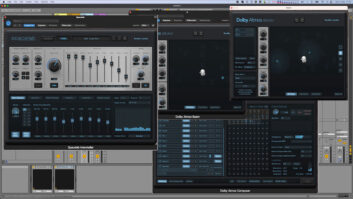

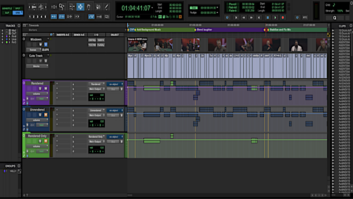

Today Dudley composes mostly on piano, mainly in her home project studio, and spends about six weeks on a 40-minute score. Her recording spaces rotate between CTS, Whitfield Street, Angel and AIR studios in London and often involve her favorite music editor-husband Paul Dudley-who has also served as a collaborator, engineer and producer. She talked about her multifaceted past by phone from her uK home a few months ago. She had just returned from a short u.S. tour with Art of Noise in support of their first album in almost a decade, The Seduction of Claude Debussy. On that drizzly, autumnal evening, she was looking forward to the release of a few projects: a 20th Century Fox film Monkey Bones, which mixes live action and animation, and NBC’s The Tenth Kingdom.

How did you begin composing for film after working in pop music?

I had actually always wanted to be a film composer, but when I was at college there didn’t seem to be any easy route into it-or any route into it at all. I found myself in this pop world and arranging things for people and dealing with orchestras and string sections, and I suppose I thought I ought to be doing this myself.

I started doing a few commercials, and I did some commercials for Tony Kaye, the director of American History X, which were very well received, and it was only ironically by being in the Art of Noise that people started being interested in me to do film scores. We were asked to do a film score for a comedy called Disorderlies. It was probably over ten years ago, and it was for a fairly major studio, but it wasn’t a great film. But for me, it was a great opportunity to get started, and I found that I really liked the work, and it really suited me.

Was it the [Art of Noise’s] “Peter Gunn” cover that gave people ideas?

Film people sometimes make very obvious connections, and obviously they thought, “Ah, here we are-a new instrumental-sounding band, maybe a new sort of Tangerine Dream.”

How do you think your pop-music background applied to film composition?

Well, everything helps. I think the thing about being a film composer is that you have to be pretty eclectic-be able to turn your hand to all sorts of different styles and genres and be familiar with the latest rhythms and the range of an obscure instrument.

I think being studio-literate helps because obviously I’m not intimidated by the studio, and I never have been. I’ve always thought it was another part of the creative process.

How do your classical music studies fit in with film work?

Film scores are often based on short themes, and it helps if you’ve got some way of developing these themes and making them sometimes last four minutes and sometimes last 40 seconds. One ends up doing it subconsciously. But you realize looking back on it that you’ve used fairly mainstream classical music techniques to do it.

Suppose you had a few notes of a theme. It might go “da-da-dum.” If you keep the same melody but change the rhythm of the notes, maybe half it or double it, you find yourself going off on a new tact and getting some new injection of life into it.

I always think it’s important to choose your initial theme very carefully because you’re going to be married to it for a long time. You might have to generate an hour’s worth of music from a very short, little piece of theme.

Do common themes run through all your scores?

If there’s anything, and it probably runs through everything I do, it’s that I’m very interested in the color of sound. And I’m very interested in the juxtaposition of different things, ethnic instruments juxtaposed with symphonic instruments, and I’m interested in the ancient and the modern. I don’t know why, but it has always been something that’s fascinated me, from when I first heard a symphony orchestra I wanted to know how those sounds were made.

What has been your favorite score?

In retrospect, my favorite work is The Full Monty because I got an Oscar for it. But it was really hard work at the time. Sometimes comedy is not a bundle of laughs to actually do.

We found this song [“You Can Leave Your Hat On”], a Randy Newman song. There was a version with Joe Cocker singing it, which they laid on the film, but for various reasons it wasn’t right. Tom Jones was really high on the wish list of people to do this song, and I think because I already knew Tom and had done a record with him [Art of Noise’s cover of Prince’s “Kiss”], I was probably top of their list to do this score.

Tom, I could tell when I first spoke to his manager, was a little bit nonplussed when I talked about the subject of the film and thought maybe, “Why is Anne doing this film? It doesn’t sound very promising. It’s about six unemployed steel workers who start to strip to make a living.” And I think Tom might have thought I was a bit… classier than that. [Laughs] Anyway, I managed to persuade him to do it. I said: “No, it’s really good, Tom! It’s not just about that. It’s all about the human spirit and triumphs in the face of adversity and all that sort of stuff.”

Anyway, Tom actually liked the film very much and was able to fit in a recording session to do it though he was actually on tour at the time, and we had to do it in a really short period of time, in an afternoon up in Newcastle.

What was the rest of the score like?

Well, what we devised for The Full Monty was a little sort of odd band full of slightly unusual instruments that you wouldn’t normally put together, like a harmonica and an acoustic guitar and a baritone sax. The thought process behind that was that these men who come together and form this group-they’re all very, very different and have different personalities, and you think, this is never going to work when you see them first rehearsing together. And in the end, it all comes together, and they do this marvelous show.

So that was the reason behind getting this weird little band together, and that proved to be very much a spur to doing something different because with a group like that you have to do quite quirky, interesting harmonic and rhythmic moves. The reggae thing really seemed to fit. That sort of loping rhythm seemed to fit the rhythm of the piece.

How did it feel to get the Oscar?

That was terrific because I’ll have to say right up until they announced my name, I thought I was a rank outsider.

Let’s talk about your composition process. When do you get a first look at the film?

I never write anything without looking. I prefer to see a rough cut of the film rather than read a script. I find it difficult to get the feeling of the atmosphere of a film from a script.

What sort of thoughts do you have when you first see a film?

usually one or two things happen: Either you have an idea straightaway-the sort of sound that you want or the instrumentation or one particular sound that you want to feature-or you don’t.

With American History X, I watched it a couple of times, and nothing came to me musically. It’s quite a difficult film to watch, much less conceive of music for. But after a while I thought this is really the story of two boys, Derek and Danny. I thought maybe this can give me a starting point, and I can use a boys choir. I put this idea to Tony [Kaye, the director], and he thought about it for a day, and then he rang me up in great excitement to say, “I thought about the boys choir. It’s brilliant! I love it! It’s perfect!” He said, “It’s very Nazi, as well, so just go with it. It’s wonderful.”

So sometimes these ideas take a little while to sink in, and the greatest thing you can have when you compose a film score is a bit of time to think before you have to charge straight in and do it.

How do you usually structure a score?

Once I’ve had my thinking time and have worked out the instrumentation and sounds I want to use, I like to start at the front. I like to start at the beginning and make the music develop in line with the drama developing. I’ve talked to other composers about this, and they don’t all do it this way. Some people like to find the emotional center of it and work from the climax and then work backward and work forward, so I’m still experimenting with the actual way of doing it. Because of the nature of film nowadays, you very rarely get a completely finished film to work with, and if you did start at the beginning, you might find that they’ve changed the beginning after you’ve written the first cue.

How many pieces do you normally like to have in an orchestra? And do you have a favorite setup?

It depends. There’s a great difference between having 20 in an orchestra and having 70 in an orchestra. Seventy is a big sound, a symphony orchestra sort of size, and 20 is a lot more intimate, and you can hear a lot more of the individual instruments rather than the wash of symphonic sound. It depends on what you want to do-American History X used a 70-piece orchestra.

I’ve tried several different things with setups. Sometimes in films it’s nice to have violins on either side, rather than on one side, so you’ve got more of a stereo picture with the violins. Sometimes it’s good to have the basses in the middle.

What about your use of choirs and choral parts? It’s really distinctive, and effective, in American History X, for example. Why do you gravitate toward them so often?

There’s an immense range of emotions you can get from a choir. In American History X, it’s a boys choir. In Ancient and Modern, it’s a choir of 16 or 18 people. It can be so many things: It can be very eerie, it can be very warm, it can be very disconcerting, it can be very glassy sounding. I’m very drawn to it.

Art of Noise doesn’t put the emphasis on vocals very much, ironically.

Yes, it’s really the sound of the voices, the sound of the words, the sound of the sound that we’re interested in. We’re not really interested in doing pop songs that say “I love you, and don’t you forget it” sort of thing.

What made Art of Noise get back together for The Seduction of Claude Debussy?

I think there were a lot of things really. We all shared an admiration of Debussy both as a musician and as sort of an icon for the 20th century. It seemed like an interesting idea to go right back a hundred years to find the source of some new ideas now.

Did you have any idea what kind of influence you’d have on others with your sampling work in Art of Noise?

It actually had more than I ever thought. Lots of people claim to have been influenced by us, groups like the Chemical Brothers, Daft Punk and Moby.

When we did [the first record in 1983], we had no idea that it would be successful. I thought of it as quite an avant-garde, experimental group-if anything, we might have a little bit of cult success-but I didn’t see us having big hit records.

What about Ancient and Modern-how did that recording come about?

It’s the first album I’ve ever done which is, if you like, a solo project, although it seems ironic to call it a solo project because there’s probably 60 musicians on it. But it’s a solo project in as much as I’m not collaborating with anybody else. Obviously in Art of Noise, I’m just part of the group, and when I do film scores, it’s always in collaboration with the director and other people involved.

I wanted to do something that had a purely musical inspiration, and I was inspired by the sound of choirs and the English pastoral music I used to hear when growing up. I was also inspired by the textures and rhythmic vitality of the so-called minimalists, Philip Glass and John Adams, and I’m always intrigued by the sound of the recording studio. I wanted to make a classical piece that was actually designed to be a CD, not designed for performance.

What sort of recording techniques did you use in making Ancient and Modern?

It’s a classically conceived record, but there were occasions when I recorded the choirs separately from the orchestra, overdubbed them, and doubled them up and did the percussion in layers. Nothing particularly tricksy, but things that classical recordings generally don’t do.

What do you find so modern and relevant about 500-year-old source music, in the case of “Coventry Carol,” on Ancient and Modern?

I think that music has an endless life. People grew up with some of these tunes, and they can be immensely nostalgic. The actual nuts and bolts of them are so wonderful that composers are always going back to the past. There’s a lot of this sort of thing going on: borrowing and recycling. It’s very ecologically friendly, I think.