In the early 1970s, a few bands began taking rock music in a new, more complex direction, as they left the 60s behind. YES and Emerson, Lake & Palmer were two such groups – both of whom recorded their memorable, earliest albums at the same studio – Advision – and with the same engineer, Eddy Offord, who eventually would forgo ELP and focus solely on Yes.

Offord had come to Advision – a studio known for, among other things, producing audio for advertising (thus AD-vision) – the way many young engineers did in England in the 60s – he answered an ad. “I was 18 or 19,” in 1966, “and my dad had a yacht, which he took to the south of France, leaving me some money to join him over there. And, of course, I blew the money,” he recalls. “So I looked in the paper, thought I might pump gas or something.”

Following a “Training Sound Engineer” ad, he went for an interview, and was immediately taken with what he saw and heard. “I was so hooked, listening to music coming out of those big speakers. It was amazing.”

Starting as an assistant engineer, running tape machines, he worked under studio boss Roger Cameron, working commercial and film scoring sessions. He eventually got his own projects, though, he notes, “Being the low man on the totem pole, they always gave me the dodgy sessions.” In Spring 1968, though, one of his artists, Brian Auger, Julie Driscoll and The Trinity, had a hit with a cover of Dylan’s “This Wheel’s on Fire,” putting Offord on the map as a staff engineer.

Advision, at that time, was located on Bond Street, just down from Oxford Circus. There was one main live room, where scores were recorded, with an additional “film room,” where voiceovers were recorded for advertisements.

There was an Ampex 16-track tape machine, with, at that point, a fairly antiquated console. “You had to keep oiling the faders, or else they’d crackle as you moved them. It was pretty bad,” he laughs.

Yes, meanwhile, were ready to record their second album for Atlantic Records, Time and a Word, at the end of 1969, and decided to make the move to Advision. “It was the next step up for us,” notes founding member Jon Anderson. “It was well known as a great studio, and they were among the first in London to have 16-track. Most studios then were in a back room somewhere. This was big – perfect for what we were wanting to do.”

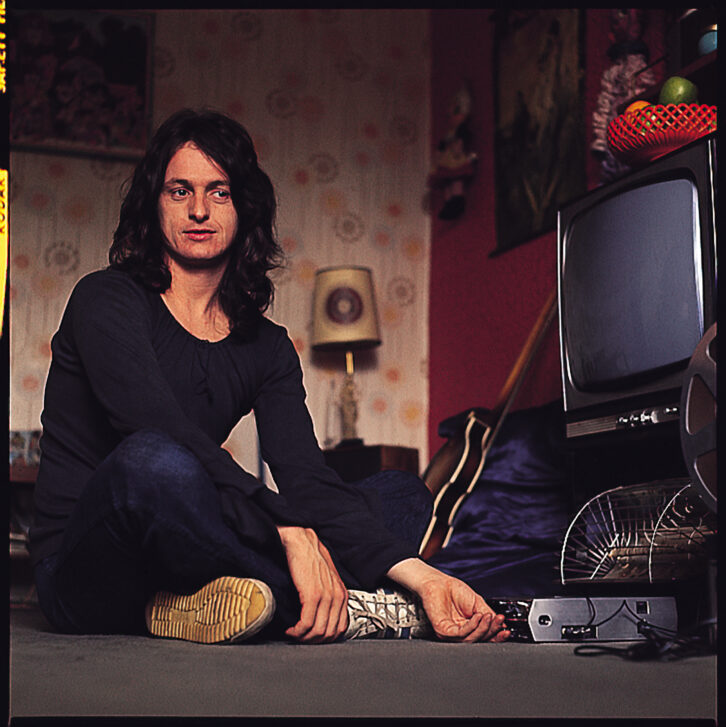

Working with producer Tony Colton, the sessions were assigned staff engineer Offord, who immediately clicked with the band, both musically and personally. “He was a very intelligent guy,” says Anderson. “You had five very interesting, talented musicians, and one engineer that was equally as intelligent, and talented in his own world. Plus, he was a total hippie. He became like a sixth member of the band.” Notes Offord, “I had no idea what ‘progressive rock’ was! I’d never heard anything like it.” But, regardless, he had an innate understanding, says keyboardist Rick Wakeman, who joined the band for their fourth album, Fragile.

“You had to have an empathy with the bands you’re working with – and Eddy had that,” he notes. “Everybody in the band, in their own way, was a bit off the wall – I wouldn’t say ‘out in left field,’ they were more out of the ballpark! We were all a bit nuts in what we wanted to do and how we wanted to do it. And Eddy was like that, as well. Plus, he knew Advision intimately, inside and out, because he’d been brought up there. The whole mixture worked extremely well.”

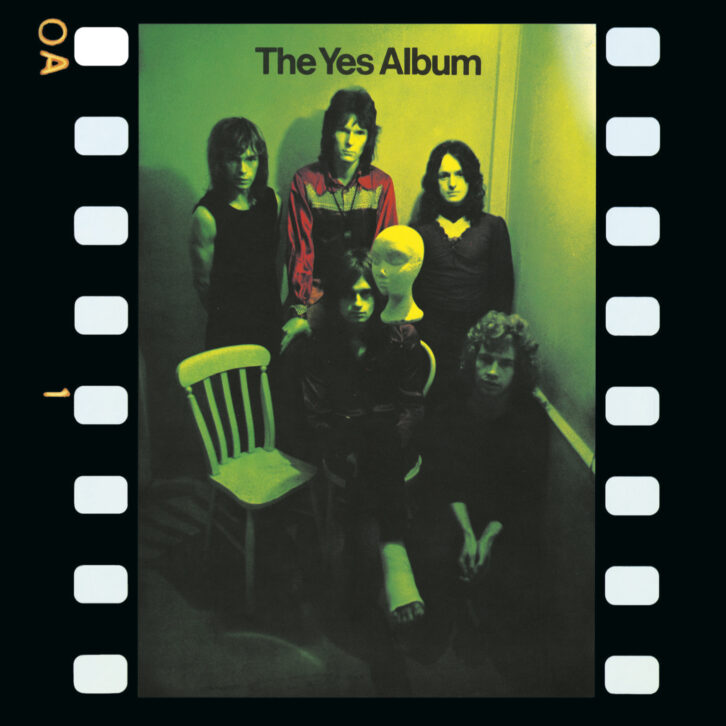

Time and a Word was released in late July 1970, and unfortunately didn’t do particularly well. Atlantic was willing to give Yes one last shot, and for their next album, the band asked Offord not only to engineer, but also produce with them. “That was my first gig as a co-producer,” Offord says, “which was pretty unheard of at the time. I think Glyn Johns and I were among the first. Plus, I got paid double!” receiving staff pay as Advision’s engineer and paid as a producer by Atlantic. Notes Wakeman, “That was the start of the end of the in-house engineer. Eddy was part of that revolution.”

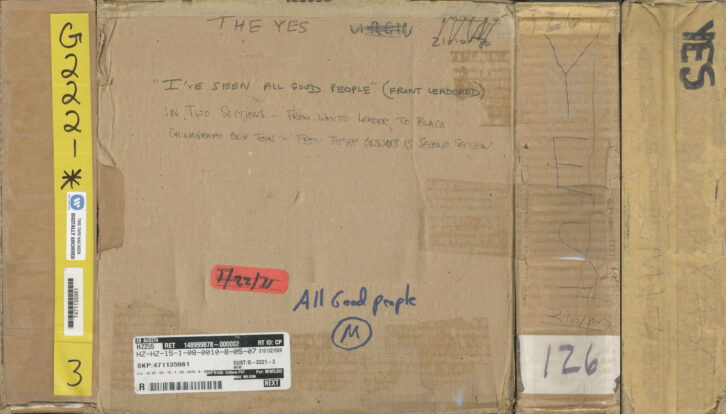

I’VE SEEN ALL GOOD PEOPLE

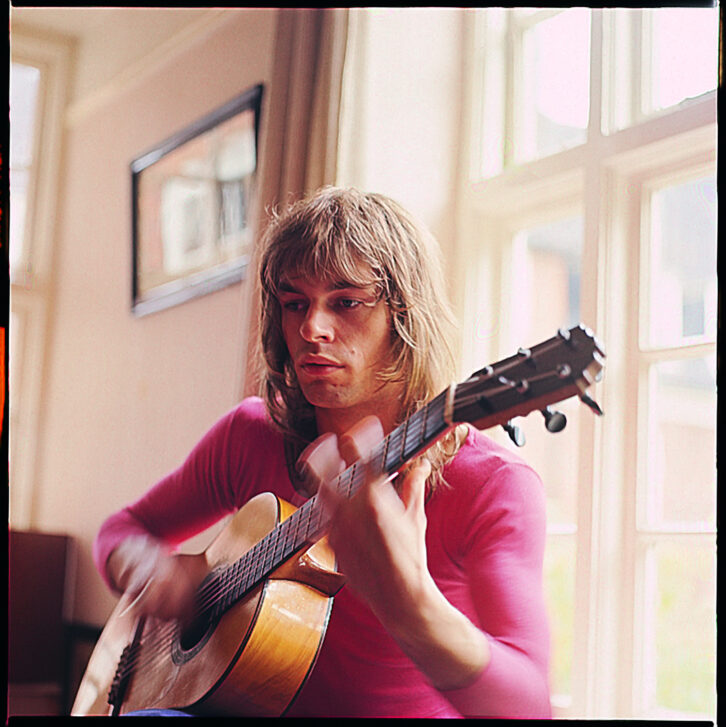

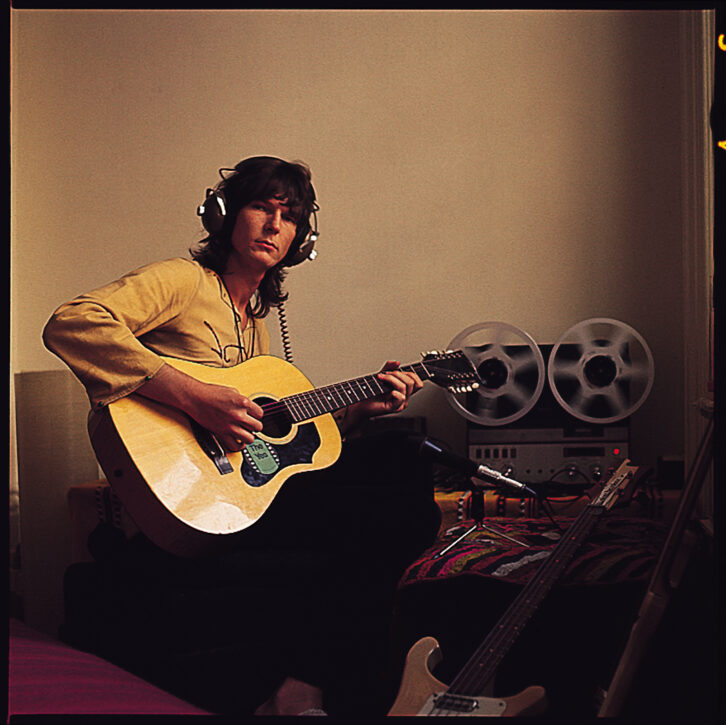

Even before recording of that new album, which would become The Yes Album, there was change afoot in Yes. Founding guitarist Peter Banks was asked to leave in April 1970. “We’d been on tour, and trying to get into some new music, and Pete just wasn’t that into it,” Anderson recalls. Coincidentally, around that time, the singer had seen a band called Bodast opening for an act at London’s famed Speakeasy. “I walked past the band, and nobody seemed to be listening – and there was this guy, playing a beautiful Gibson guitar – who was quite extraordinary. And that was Steve.” The group canceled its gigs in early May, and, while discussing possible replacements for Banks, bassist Chris Squire suggested, “What about Steve Howe?” Says Anderson, “I said, ‘I saw him last week.’ So we connected with Steve, and, within a month, my whole world changed, musically. He could play classical music, jazz fusion, rock and roll – so many different styles. It was fantastic.”

While, in London, they would typically rehearse at a place in Chasper Avenue, the band now spent 3 ½ weeks in May rehearsing on a farm in Devon, Langley Farm – which Howe eventually bought and still owns – developing new songs for the upcoming album. “I just thought it was important to all be together,” says Anderson, “to wake up and make music together, spend all day having fun and just enjoy music and each other. We bonded like crazy.”

There was another important goal for the rehearsals. ”We had had two albums that had done okay, but not very well,” Anderson states. “Atlantic was giving us one more chance to make it work. So we wrote these songs, then went on tour and played them, and they seemed to work. Then we went to the studio, knowing that it felt good to the audience, so it was going to work for us.”

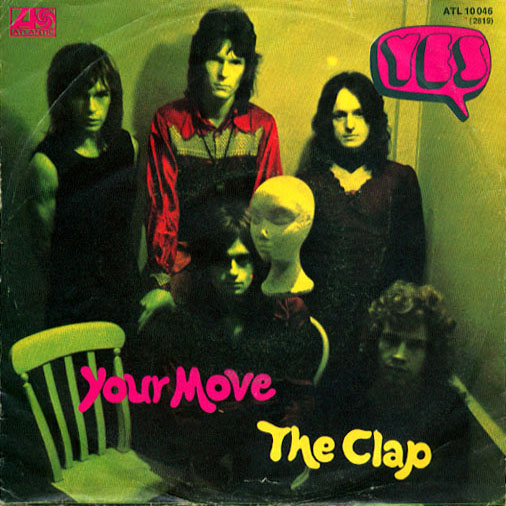

By June, they returned to the road, playing both songs from Time and a Word, released the 25 of that month, and some of the new songs, including Howe’s acoustic “Clap” – recorded by Offord at The Lyceum on June 17 (“I think I had a Revox and a couple of mics,” he notes). A studio version of the song was recorded, though it remained unreleased until 2003.

Offord spent August and September recording ELP’s first album, and, beginning October 11, moved on to the first sessions for The Yes Album. The sessions would continue through October 30, with Yes sprinkling in session dates on off days from their still continuous road gigs (actually returning to the studio on November 16 to record “Perpetual Change”). On October 21, they began recording what would become “I’ve Seen All Good People.”

Around this time, Anderson had begun reading Hermann Hesse’s Journey to the East – “It’s all about ‘take a straighter, stronger course to the corner of your life,’ starting to search for that positive place,” he explains. “Because it’s time is time and time – I actually sang that and started to try and write down what I was trying to say, about a real understanding of why we’re here, the idea of your time on earth,” becoming the iconic chorus of “Your Move,” “Cause it’s time, it’s time in time with your time, and its news is captured for the queen to use.” “It was a really nice line,” which he applied to a simple three-chord progression, while writing at home.

During rehearsals, he suggested to drummer Bill Bruford and bassist Chris Square to create a simple bass-kick beat, which would remain through the song. “It’s like a heartbeat.”

The trouble with two guys playing a constant, consistent heartbeat for 3 ½ minutes is that it’s. . . . hard. “They came into the studio with an idea, ‘Okay, we’re gonna do this bass and drum kick,’ very simple pattern, ‘and we’re gonna put vocals over it,’” Offord recalls. “Well, that sounds simple and easy when you hear it, but trying to get that bass drum and bass in sync was almost impossible.” So Offord created a loop from a recording of a few bars’ worth on ¼-inch and tracked several minutes’ worth onto Track 2 of the 16-track tape. Says Anderson, “He told us, ‘Just follow the tape.’ Probably one of the first click tracks ever done.”

Immediately after, Howe’s rhythm guitar was recorded onto Track 4, played on a small, 12-stringed Portuguese instrument called a vachalia. “Steve was always collecting these bizarre instruments,” Offord notes. “He just said, ‘I want to try this one.’ He knew what he wanted. It goes all the way through the song, there’s no other guitar.”

Bruford tracked two passes of a shaker onto a pair of tracks, and keyboardist Tony Kaye record his Hammond organ onto Track 7. Offord would place a pair of mics at the top of the Leslie cabinet, with another at the bottom to capture low end, and mix them together into a single channel. This was accompanied by a deep, growling bass line, played by Squire on a pedal bass system he often used onstage, a Dewtron Mister Bassman. Says Anderson, “The keyboards would creep in, and eventually we do a big keyboard section, with a church organ sort of sound.”

With the basic track recorded, Anderson’s lead vocals were then tracked. For Yes recordings, Offord says, vocals were never sung during basic tracking. “When we laid down tracks, we always did just drums, bass and a scratch guitar – the latter just to let the other guys know where we were in the song; it was never used. I never heard a vocal until it was time to record it,” though Anderson was always in the live room with the rest of the band during tracking. “He was very involved in the arrangements.”

Offord recorded Anderson’s lead vocal (using a Neumann U64, as Offord used for all vocals), followed by several passes of his harmony vocals.`

Key to any Yes recording is complex backing vocal parts, often contrived by Chris Squire – or, as he was known to the band, “Fish.” “That was partly because he was a Pisces,” Offord explains, “but more due to the fact that he was never on time. You’d call him up, and he’d say ‘I’m in the bath,’ so it was ‘Oh, Fishy’s in the bath.’” Squire had sung in a choir in public school, and was rather adept at creating interesting parts – in this case both regular harmonies and interesting counter-vocal lines – for he, Anderson and Howe to sing.

Interestingly, though the trio would rehearse the parts singing together, they were never recorded together – each musician recording his part separately. “It’s very hard, three people around a microphone, to get the sound we were looking for,” explains Anderson. “We really wanted it to sound very different than the normal bunch of guys singing. So we double-tracked each other,” beginning with Anderson’s unique high voice, followed by Squire (middle harmony) and Howe (low). “Alone, Chris’s voice was interesting, but blended with Jon, sounded really good,” Offord notes. “Steve was the least trained vocalist, so his parts would take a little more time. He had a very unique kind of voice, too. I don’t know what it was – the three of them sounded great together, didn’t they?”

The backing vocals were each recorded on their own tracks, then Offord mixed the pairs of trios down to two tracks (i.e. two sets of harmonies), freeing up the base tracks to do more. In all, seven of the 16 tracks of the tape were devoted to vocals for “Your Move.”

Included in that was the second of two tips of the hat to John Lennon, Anderson mentioning “Instant Karma” (which had been released earlier that year) in his main lyric, and a harmony line of “Give peace a chance,” heard towards the end of “Your Move” (though it was recorded throughout the song, muted until the end section). “We were listening to a mix of the song,” Anderson recalls, “and I said, ‘Why don’t we go in and sing ‘Give peace a chance.’ We got a bunch of people to come in and help sing along, and we double-tracked it, and added it in the distance, so you can just about hear it.”

One final touch was the addition of two tracks of a recorder, played by a fellow named Colin Goldring, of the oddly-named band, Gnidrolog, whom Anderson had seen a few times. “It was originally supposed to be a Mellotron flute,” he informs, “but it just sounded too Beatley.”

While rehearsing “Your Move” at Advision, on a break (“to go outside and roll a joint of something”), Anderson returned to hear Howe and Squire playing an infectious, punchy riff. “I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool, if we get to the end of ‘Your Move,’ with a big chord, and then go into that riff?’ And that’s what we did.”

Anderson suggested the band modulate a few times, “and then I’ll come up with something,” which became the line, “I’ve seen all good people turn their heads each day, so satisfied, I’m on my way.” “I started singing that riff – the idea that we played in this band, come and see our show, they’re the good people, and we’re happy to see them, and we’re on our way after seeing them.”

Offord tracked the live session, with Bruford’s kick and snare mixed into one track, his accent tom hits on another. Bruford, at the time, played a fairly simple Ludwig kit, Offord says, unlike “the real huge kit Carl Palmer had.” He distinctly recalls the drummer not dampening his snare, as was the common practice at the time. “That was a very dead sound. We talked about it, and he said, ‘I really want a ringing snare drum.’ And that became his unique sound.”

Squire accompanied, punching away on his Rickenbacker, his Marshall cabinet miked “a few feet off,” with an AKG C28. “His basic sound was pretty trebly – that was his trademark,” Offord notes.

Howe played rhythm (heard on the left in the recording) – again, a scratch track, to be recorded properly as an overdub, as was his second part, the song’s lead. “I don’t ever remember keeping anything he did live,” Offord relates. Of course, the guitarist played the part on his trusty & beloved Gibson ES-175D. “He was so precious about that guitar, it was like his baby! On the very first tour I went on, we didn’t have a private jet – we traveled 1 Class. But he had to book a seat for his guitar – he didn’t trust the guy the luggage handlers. It had to be next to him on the seat.”

The band’s vocal chant of Anderson’s line was recorded as described previously – three separate parts, mixed together, and repeated, to create a pair of harmony vocals.

Once the rhythm had been completed, Anderson notes, “Then the final thing is how to get out of there.” The solution was to modulate the vocal line in downward steps, the vocals following Ton Kaye’s organ and Squire’s Bassman bass pedals, which eventually fade out to just leave the band’s vocals bare, as the song fades out. Three more three-part passes of the “I’ve seen all good people” line were then recorded and placed at the beginning of the song, as its intro. “We were singing it, and I said, ‘Oh, why don’t we stick it in the front,’” Anderson says.

The two sections were edited together by Offord, the tape box clearly marked, “In Two Sections – From white leader to black Chinagraph over join – From there onwards is second section.”

“Your Move,” on its own, was released as a single, backed with the live version of “Clap” in the U.S. (“Starship Trooper” in the UK) on March 5, 1971, three weeks after the release of The Yes Album. “Yes was never built to be a commercial entity,” Anderson says. “We didn’t make it as a commercial song, just one we could perform onstage the leads into the next piece. The last thing we thought about was, ‘Are we gonna get a hit record?’” They got one nonetheless.

ROUNDABOUT

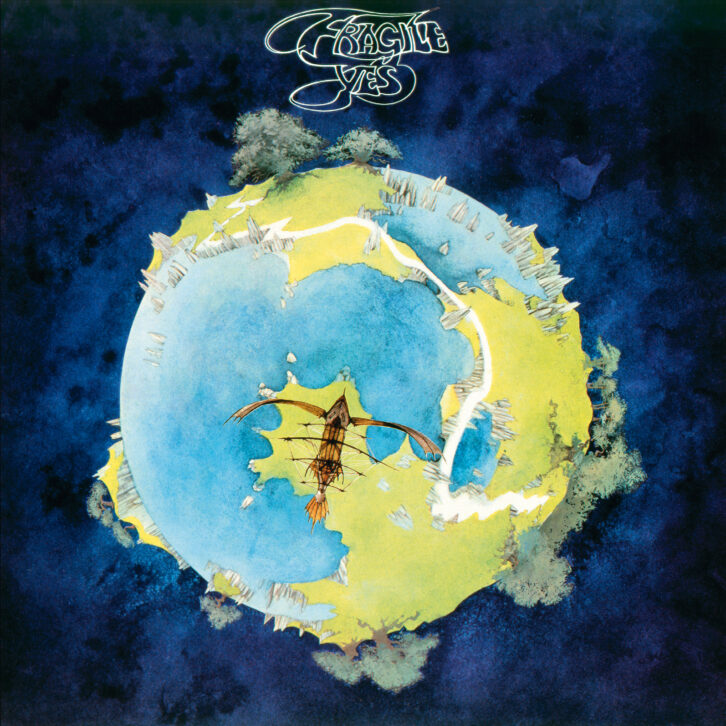

The Yes Album was released on March 19, 1971, amid Yes’s seemingly endless touring dates – from the completion of that disc to the recording of their next, Fragile, in August that same year. Rehearsals for Fragile began in the last week in July, but not before an important change to the group’s composition.

On December 9 the year before, Yes had played at Hull University in the UK. Opening for them was a band called Strawbs, which featured a 21-year-old, long-haired keyboard wunderkind named Rick Wakeman. “We watched this band play – and we never forgot about him,” Anderson recalls. Wakeman was equally impressed. “The stage set was so un-rock’n’roll,” he remembers, noting the absence of giant Marshall stacks, smaller SunAmp and Fender Twins in their place – and all, including the drums, miked for the PA the group had acquired from Iron Butterfly. “They were one of the first bands to mic everything onstage,” adding, “And they didn’t have the usual 6’-3” singer with long black hair – on came this diminutive chap, about 5’-3” with an alto voice. And I thought, ‘What on earth is going on?’ The whole thing was wrong on paper, but I listened, and I loved it.”

Wakeman had been doing session work in London since 1966, when he was 16, joining Strawbs two years later. “Even after I joined Yes, I still had a dozen sessions left on the books to complete for others,” he notes.

By mid-summer 1971, Yes had grown restless with keyboardist Tony Kaye’s reluctance to venture away from the basic piano and organ and try some new electronic instruments – something which Wakeman relished and was able to fulfill. “Rick is a schooled, classical pianist,” Anderson notes. “He could read music and had incredible knowledge of orchestration. He had about five or six keyboards at that point – in those days, three of four was great. He offered us so many sounds that we didn’t previously have available.” By late July, upon their return from a tour of the States, having never forgotten him, Chris Squire gave Wakeman a call and invited him to join the band, just in time for rehearsals for the new album. “All of a sudden, we were the REAL Yes.”

Immediately upon their return in the last week in July from their first tour of the U.S., mostly opening for Jethro Tull, the group convened – now with Wakeman – at a rehearsal space to work up tracks for the new album. “It was in Shepherd’s Market, in Mayfair – above a high class brothel,” Wakeman states. “Cause I remember being quite confused as to why it was summer, and there were all these women in fur coats outside. We rehearsed upstairs, and they rehearsed downstairs.” Notes Anderson, “It was the cheapest one we could find.”

Working for about two weeks, until the second week in August, the group drafted four new band songs, which would be supplemented in the studio by four bandmember-centered tracks. The first piece worked on was the complex “Heart of the Sunrise,” inspired by a King Crimson riff Squire had become enamored of. “I asked him, ‘What happens after that, Chris?’ and he went, ‘No idea,’” explains Wakeman. “The music was a giant jigsaw puzzle, of people bringing different pieces – ‘That’ll slide in there,’ ‘This will slide in here.’ Anything we wanted to do, the answer was there amongst the band. I’d never been in a band quite like that.”

A day or so after the release of The Yes Album, the group was traveling in its van from a show in Aviemore, Scotland, and Anderson and Howe began a new song. “He was playing guitar, and I’d sing the melody, with a mock lyric,” the singer recalls. “I began writing down lyrics, as I saw the scenery.” Said scenery included mountains which would appear suddenly from within the clouds (“Mountains come out of the sky, and they stand there”), a lake in Glasgow (“In and around the lake”) and countless roundabouts (traffic circles), which became the song’s title, “Roundabout.”

On writing together with Howe, Anderson notes, “It was very simple – he’d start playing a guitar groove idea, I’d start singing a melody. Then, after I’d sang something, I realized that I needed something different, and I’d talk to him about it – maybe changing the guitar style or bringing some different chords, try something else, and then ‘Perfect.’ You basically stick it together with Super Glue.”

During the rehearsals, the group spent a few days on “Sunrise,” and then shifted gears into “Roundabout” – though Wakeman notes that neither song had a title at that point. “We just kept playing the verse bit, and then little things started happening. We needed to go somewhere, so rather than just stop it, we the middle section,” a sort of jazz break. Anderson threw in a quiet ballad section after that, and at one point, Wakeman says, “I can remember Bill Bruford shouting over the drums, ‘We need an organ solo!’” which would come next.

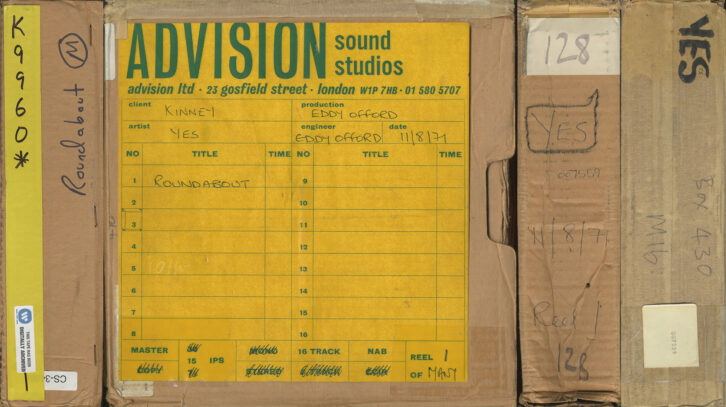

At the beginning of the week of August 9, Yes arrived to work once again with engineer/co-producer Eddy Offord (assisted by Gary Martin) at Advision Sound Studios – though, this time, at the new Advision. The original studio, at which The Yes Album was recorded, was located on Bond Street, near Oxford Circus. The company built a new studio, located at 23 Gosfield Street, complete with a custom-made 24-channel console built by Swedish engineer Dag Fellner – a vast improvement over what Offord was used to at the old location. In addition to a desirably dead live room, Wakeman notes other smaller rooms were available – one of which was used to separate Squire’s bass cabinet – particularly the noise the amp itself produced – from the rest of the instruments in the main room.

Working with progressive rock, particularly Yes-style, was, of course, complex, requiring tracking of different sections, one at a time, with skillful editing by Offord to create the master. “We would put the basics together in rehearsal, and then the other 25% would happen in the studio,” Wakeman says. Explains Anderson, “How we got into recording long form pieces was a very simple concept. You create a musical structure, very well-organized, and then record 1-, 2- or 3-minute sections, because people start going, ‘What’s the next part?’ and forget the ending of the first part. So you record a rough concept demo and go, ‘That’s what we’re gonna do,’ and then record each part.”

“I’d give them a lead-up of the end part of the previous section in their headphones, and they’d come in and do the next section,” Offord explains. “But they were such perfectionists, wanting to make sure the kick drum, for instance, was right on the money. If someone was unhappy with a little section, they’d want to do it over. So there were splices all over – there are probably two or three edits just in the verse sections on ‘Roundabout.’”

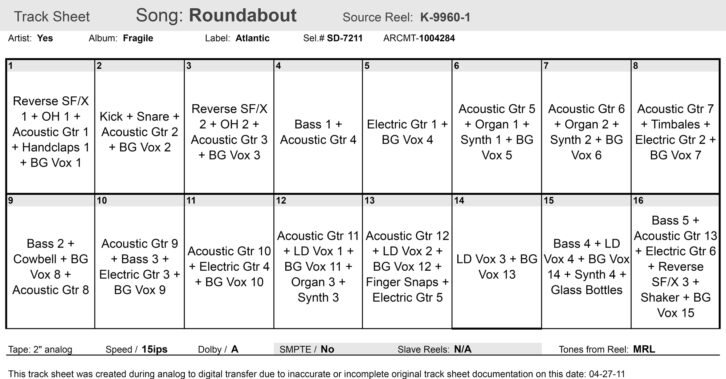

Adding to the complexity of recording Yes was the limitations of 16-track – where do you put everything? Offord would have to look for space on an existing instrument track where a gap in the part existed, where he could throw in another instrument. Wakeman’s brief synth parts, for instance, at the ends of the verses of “Roundabout,” were placed on one of the organ tracks, in moments where the organ wasn’t playing. Mixing required skillful coordination and record-keeping – especially where instrumentation switched from, say Howe’s acoustic guitar strumming on the verses on Track 8 of the tape to Bruford’s timbales during the following jazz break section. “I would just split those off into different faders, with the EQ on one fader for the first instrument, and the EQ on the other for the second,” Offord explains.

“Roundabout,” the album’s opening track, begins with a solo guitar section by Steve Howe, a suggestion Anderson made during rehearsal, “rather than just coming in with the band right away,” he says. The part was the first thing recorded for the song, which began recording on Wednesday August 11, Offord placing a pair of AKG C28s at 45 degree angles to capture Howe’s acoustic.

The true opening of the song, actually, is a dramatic backwards piano. “We needed something to lead into the guitar intro, ’cause it was very dry coming in,” says Wakeman, “so I came up with the idea of the backwards piano.” Then it was a matter of figuring out how to do it. “The thing with Yes was, everybody in the band wanted to test themselves – to do things musically, that, on paper, you couldn’t. And the great thing about Eddy was he wasn’t the type of engineer who would turn and around say, ‘Well, I don’t think we can do that.’ Eddy always said, ‘Well, let’s have a little think how we can do this.’”

Offord took a Chinagraph marker and marked the point on the tape where Howe’s first guitar note was struck, and then flipped the tape over, playing the track backwards to Wakeman, and signaling him as the mark approached the record head, for when to strike his two-octave E minor chord. (The effect is repeated later in the intro with a C major). “He’d get used to the melody backwards, and then know when to expect the last note,” says Offord. “Today you’d easily do that with a sampler, and you could adjust it on the timeline on Pro Tools. But we didn’t have any of that.”

The three verses and choruses, which form the first part of the song, were recorded next, with, as Offord described previously, Bruford and Squire playing live, with Howe accompanying on his Gibson ES-5 Switchmaster as a scratch guitar part, which was replaced in earnest later. In addition, he overdubbed a strummed acoustic guitar. Later, it was decided to add an additional part for the first verse, with Howe playing harmonics instead, the strumming part muted for that verse in the mix.

The verses also offer a taste of things to come later in the song, with the introduction of Wakeman’s Hammond B3, recorded onto two tracks by Offord, with high and low-end miking. Wakeman supplemented the organ with a Moog accent line at the end of the second and third verses. “I didn’t have my Minimoog until after we’d finished Fragile,” he recalls. “But there was a Moog in the studio owned by Mike Vickers, so I rented it off of him for a few days, just to do the little Moog parts.”

The jazzy “mid section,” as the band called it, grew out of a bass line Squire injected during rehearsal, inspiring Anderson. “I was thinking, ‘Okay, then I could come in and sing on top of that, and Rick can do an alternate melody.’ You put things together and you hope it works.”

Squire doubled his bass line by borrowing one of Howe’s Telecaster guitars. Wakeman also doubled the bass line on his Hammond, a common practice, he says, between the two musicians. “It was very rare that what I was playing with my left hand was different from Chris – I would say 60-70% of the time it would be Chris’s lines that I was copying, and at other times, it would be mine that he would be copying.”

Bruford played his jazz-styled drum part, and later added both a timbales overdub and “saucepans” – two milk bottles filled with differing amounts of water to create different pitches. Regarding the timbales, Offord notes, “Bill said, ‘I want to put some stuff on afterwards.’ Then they’d talk about it for a long time,” he laughs, a typical experience in Yes sessions, “and we’d eventually get it done.”

The ballad section which follows, used as a buildup to the solo section that follows, features Anderson singing a quiet a chorus, with some lovely Mellotron flutes. Wakeman had acquired his Mellotron the year before, and originally played it as a string part on the recording, but then changed it to flute “because that was more what people were not expecting,” he says. The troublesome instrument was eventually superseded in his collection by a Manikin Electronic Memotron.

The solo break that Buford had suggested during rehearsals came about with much flare, featuring not only multiple astonishing guitar parts by Howe, recorded in sections, one at a time, according to Offord (and with a short Automatic Double-Tracking delay recorded to tape), but an explosive organ solo by Wakeman.

Wakeman owns two B3s – an American model (heard on Close to the Edge) and an English one, “what I call my ‘Roundabout B3,’” he notes. He recalls purchasing the latter in early 1971 at the Chingford Organ Center in Essex. Upon seeing him admiring the instrument in the store, the salesman told him its price – 1000 pounds. “When he told me that, I laughed – I was with Strawbs at the time, earning 18 pounds a week, and my rent was 8 pounds a week.” The salesman, anxious to make the deal happen, happily accepted a used instrument as a deposit. “He said, ‘What have you got?’ and I told him, ‘I’ve got an old Hammond L100 which is falling apart and doesn’t work.’ He said, ‘I’ll take that as a deposit,’” agreeing to accept 4 pounds per week for four years.

Long after, in May 1974, when his Journey to the Center of the Earth album was No. 1 and Wakeman was living comfortably, he received a letter, stating “Congratulations – you have just made your last payment of 4 pounds. You now own your Hammond organ.” “I’d forgotten all about it!” he laughs.

The organ was played through a Simms-Watt 100 W amplifier and a pair of Simms-Watt cabinets, made by Dave Simms and Richard Watts, which Wakeman had bought the year before. “I actually used to make a little bit of extra money early screwing the speakers into their cabinets in their little shop in West London,” he remembers. His current bandmate, Trevor Rabin, actually owns a pair of the 4 x 12 cabinets. “When I saw those in his house, I couldn’t believe it. I probably screwed the speakers into those cabinets.”

That amp setup provided a fiery grind to Wakeman’s organ sound, much like that which he admired in another player of the day. “Jon Lord was someone who I admired – he created a Hammond sound that was really individual, and he had an individual style of playing, too, which I loved.”

While Offord says most of Wakeman’s parts would be recorded as overdubs, the keyboardist recalls this one being played live, done in the section’s single take. “Everyone was jumping up and down, blown away. It was really special,” the engineer remembers. The consummate professional, though, Wakeman considered offering an improved version. “We played it live, and after we listened back to it in the control room, I said, ‘Well, I might go in and have a few more goes at it.” Bruford, however, would have none of that. “He said, ‘The hell you will! That’s live. Proper solos are live. Leave it. Don’t touch it.’ I think he threatened to kill me if I did.”

Upon completion of tracking, and Offord’s skillful editing of the master of the various parts, the following day, Anderson recorded his lead vocals, double-tracking many lines, itself a tedious process. “We would have to do a lot of punching in, so he could get the phrasing exactly right,” Offord explains. “So we would be doing it line by line a lot of the time, to allow it to be spot-on.”

The background vocals were recorded in the same manner described for “I’ve Seen All Good People,” with each member recording their harmony line separately, doubled, and then summed into pairs of group harmonies, to be mixed into stereo.

Afterwards, Anderson says, “We got to the end of the song, it just seemed it needed something else.” He grabbed his guitar and started singing the song’s “Da da da” ending, quickly joined by Howe and the rest of the band. “We just recorded as we played it, very open acoustic, and I’d sing along. And we just kept adding vocals.” A “Three blind mice” melody is also heard, an idea of Wakeman’s (though he does not sing it). “I don’t even sing in the shower,” he says.

With that, the song was complete. Fragile was released not long after, on November 29, with “Roundabout” as its lead track. The song itself, which clocked in at a lengthy 8:29, but for its single release, Atlantic’s engineering team came up with a much-shortened single edit of 3:27, missing a good many elements of the song. “We were on tour, and we heard it on the radio, and when it came to the middle section, it wasn’t there,” says Anderson. “Nobody talked to us about it.”

“At that time,” says Offord, “everybody was crying out for 3 ½ minute singles. They did the edit, sent it over, and we were kind of unhappy about it, but we said, ‘Okay.’”

[That edit, along with oodles of other rarities (including 5.1 surround and instrument-only mixes), are available on a series of Yes catalog reissue CD/Blu-ray sets released over the last few years by British label Panegyric. For each, the albums have been skillfully remixed to recreate Offord’s mixes by Steven Wilson, known for his work in the genre.]

“Yes albums,” says Anderson, “from the first second to the last, are a complete idea. It wasn’t a series of three hits and the rest is filler. We just wouldn’t go there. The fans deserve a full commitment, musically. And that’s what Yes music is.”