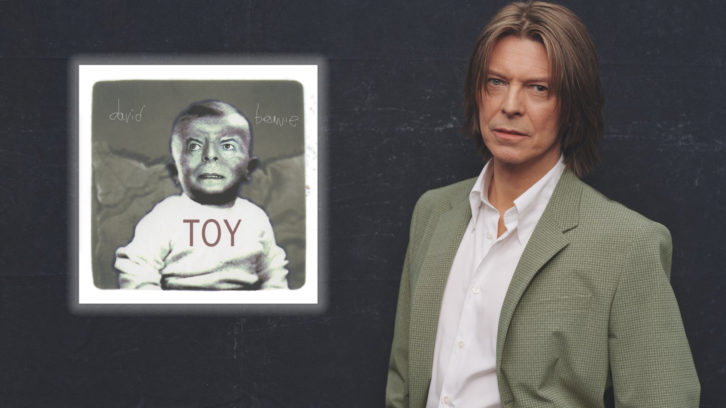

David Bowie had many personas—Ziggy Stardust, The Thin White Duke, Major Tom and others—but by the turn of the Millennium, time had thrust a new role upon him: Rock Elder Statesman. At 53, he had become an icon with a rich musical history, and despite his perpetual focus on the future, even Bowie himself began reassessing his rollercoaster career. With producer Mark Plati, engineer Pete Keppler and a killer live band in tow, he hit the studio in August 2000, aiming to re-record some of his earliest pre-fame songs.

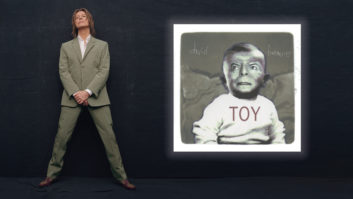

The result was Toy, a collection that became an urban legend—a lost album that only now, more than two decades after it was recorded, is being released for the first time…twice. After its inclusion in the career overview Brilliant Adventure (1992-2001) boxset this past November, the album will come out on its own as the appropriately titled triple-CD Toy:Box on January 7, 2022—the eve of Bowie’s posthumous 75th birthday. Looking back at the sessions behind the album, Plati and Keppler separately shared the full, tumultuous story of Toy (comments have been lightly edited for clarity and brevity).

Plati: In the 1990s, I did two albums with David Bowie — Earthling and Hours — and I did all the engineering on them, but when it came time for Toy to happen, my role had shifted and I was in his band as the musical director and guitar player.

Keppler: Mark is an amazing engineer, producer and musician, but when it comes to recording an entire band at once, it’s really helpful to have someone else around to engineer, especially if you’re playing in that band. He brought me onboard to be the engineer while he produced and played.

Plati: I wanted to capture this live energy and feeling of spontaneity between all of us in the studio. When I started to play with David live, I saw that he had this other energy on stage and a different connection to the songs. David was very much a band person, and fed off the energy of the band, and in turn, the band fed off of his energy.

Those songs are from ’66 to 1970, they’re all different producers and musicians, and David was pretty young as an artist then, so his input was quite different. This time, we would use one band, and of course, he had a lot more to say about it. There would be two producers—him and myself—and we would do it at one studio in one long, couple-of-weeks session.

Classic Tracks: David Bowie’s “Five Years” / “Soul Love” / “Moonage Daydream”

Keppler: We went into Sear Sound in New York in August, 2000 and spent a few weeks cutting all the tracks and doing some of the overdubs. We worked our asses off—the days went really fast. I’d get in there by 9 a.m. every day and we were usually out by six or seven o’clock that night, but we packed an awful lot of work into those hours.

The big room at Sear Sound has a custom-built Avalon desk; David may have been singing through that, I don’t quite remember. Each channel had essentially a 737 channel strip without the compressor. We also had a rack of Neve 1081s we’d hired in as well to capture drums and punchier stuff.

Plati: We took all of this fantastic analog input, used three Digidesign 888 interfaces and recorded in the computer. The owner, Walter Sear, wasn’t too happy—he was like, ‘What are you doing—you’re not using 456 tape?!’ Walter thought we were crazy. He’d come in and shake his head, but we were making a 2000 record.