When it comes to videogame audio, Brian Schmidt has pretty much done it all. Besides working on more than 130 titles for most of the major players in the industry (EA, Sony, Microsoft, Sega, et al), he was responsible for developing the original sound and music systems for the Xbox and the Xbox 360 (as well as the 360’s XACT interactive mixing tool); he started the GameSoundCon conference, devoted to videogame music and videogame sound education; and he has spoken often at industry events scattered across the globe. It’s no wonder he was honored with a prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award from his peers in the Game Audio Network Guild (GANG).

So, every move Brain Schmidt makes is viewed with considerable interest in the gaming world, including his latest foray: A 3-D audio game for the iPhone and iPad called Ear Monsters, the first of what will be a series of audio-centric games for portable devices from his newly created company, Ear Games. After so many years in the trenches, working on every sort of videogame imaginable, Schmidt has evidently decided that small is beautiful, and 3-D audio is where it’s at.

“If you think about it,” Schmidt says, “in a videogame, the video part is actually this small visual bit of this whole created world, and one of the cool things about audio—especially with surround or 3-D—is you can render the audio beyond that visual image and in effect extend the world. It’s not too much of a step to get rid of the visual image altogether and rely pretty much on sound.”

Ear Monsters is not the first “audio videogame” for iPhone/iPad—the popular horror title Papa Sangre came out in December 2010 (and was revamped this year), for instance. But Schmidt is hoping that his game will take the audio gaming experience to a new level. In Ear Monsters, creatures from another dimension are invading our world, and even though they are invisible, we can hear them around us, so our critical task is to kill them all to save our universe! It’s harder than you might think, and the dimensionality of the audio is critical to know where the foul monsters lurk.

“I’m a big proponent of the more casual arcade-style games that you pick up and play for a few minutes and then put down and then play again a few minutes later,” Schmidt says. “Obviously it’s a different experience than the big, longer, story-based games. And, of course it’s geared to headphone listening.

“The audio engine was developed by QSound Labs—which actually did the ‘virtual haircut’ 3-D audio demo that has about 15 million views on the Internet,” he continues. “They spent a lot of time shrinking their algorithms down to portable spaces, and they’ve licensed it to various handset and phone manufacturers. They have a real run-time HRTF 3-D engine they built, so I incorporated that into the game. [HRTF—Head Related Transfer Function—refers to how our ears and brain process a sound to determine its location in 3-D space. CPUs can now mimic the sound placement our sophisticated hearing is capable of.] But even the very best run-time HRTF generally won’t be as vivid as a really good [binaural] dummy-head recording. So in the game, there are a few plain old dummy-head recordings that give you some of the super-vivid images of planes flying overhead, and let me position the real-time sounds wherever I wanted them.”

Schmidt did his own binaural recordings, including some Blue Angels fly-bys he captured in Seattle, where he is based, and various ambient atmospheres that emerge as the player moves successfully through the game: “One of the things I wanted to do, and again this is sort of in the style of an old arcade-style game-play, is it’s pretty easy at first—in fact, when you first start the game you have visuals that help you out. Then, as the game progresses, it gets harder and harder until at some point it gets maddeningly tough. One of the things I do to make it more difficult to play the game is introduce additional sound backgrounds that provide some masking. So, when you get to a certain number of points, suddenly you hear some wind crop up, and then the wind gets stronger, and then the rain comes. And each of these sonic elements, as they get layered on, are full binaural recordings I did here, and they also serve to make the game tougher, because it’s harder to pick out the sound of the monster—it uses the masking effect to make it a little more difficult. I’ve got a couple of rainstorms and some thunder.

“I also use a little Wave Arts Panorama as well, which is an HRTF plug-in. So, the game sonically is a combination of mono sounds that are positioned in real time by the HRTF engine—the actual monster sounds, the monster hits sounds, the sounds when you swipe at it, the sounds you make, and so on. Then I’ve got the dummy-head recordings, and also some additional recordings that were processed with Panorama.”

As for the monster sounds, “I did some of them myself and a friend of mine at Funky Rustic Productions did some, as well. That’s a combination of vocalizations and a lot of pitch-shifting—they get pitch-shifted up, re-jiggered around and flanged, and then I re-pitch them back down again.”

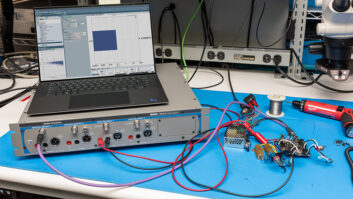

Schmidt terms his work environment “a decently equipped home studio. I’m in Sonar, but switching back to Digital Performer, which I used for a long time. I have a standard Dell i7 with 16 GB of memory. My main keyboard is a [Yamaha] Motif 88-key, which I really like—not just because it has a great piano action, it also has great sounds for these sorts of arcade games, where you’re looking for a little fanfare or whatever. My main development is on a MacBook that is running Parallels, so that with the switch of a key, I can go from three screens of Mac to three screens of Windows. I like PreSonus for audio I/Os, I’ve got a little Peavey MidiBass controller, and the standard sample libraries, like the Platinum East West.

“For this kind of work, I’ve got three different sets of headphones that I rotate through. I’ve got the Apple earbuds, I have a pair of [beyerdynamic] DT 770s that are sort of my main monitoring headphones, and a pair of Shures. I also have a pair of Ultimate Ears that I throw in randomly once in a while to check things.

“When you’re doing iPhone games, you have to do things like roll off everything under a couple of hundred Hz; worry about things getting too tinny in the highs. It’s a little funky, because the HRTF processing does a bunch in the 8 to 12k range; that’s where a lot of the notch filtering happens for your front-back distinction.”

For his initial audio game, Schmidt did almost everything himself, including programming and even the bass and percussion music that pops up from time to time. For the next Ear Games, however, he says he’ll probably farm out some of the sound design and other elements. “The first time I always like to try to do it all myself; that way when the second time comes around, and I decide I want to hire somebody to do some piece of it, I have a much better idea of what it is that needs to get done, or what kind of problems they might have. Now that I have a game template and an engine and figured out the whole iOS thing, the hope is the next games go even more smoothly and they get better with each one.”

Schmidt is purposely vague about what will come next from Ear Games, noting, “I’ve got about three to four games penciled out right now. One is pretty detailed penciled out, the other three are sort of sketch-padded out. One is a little more story-based, and I’m thinking it would be great to get some ‘name’ voice actors to do that. Whatever we do, though, I want it to have straightforward, quick-to-learn game mechanics that can be mapped well into an audio experience.”